"Our world has made it very easy to ignore to the suffering" How to create illustrations which truly convey the experience other people and show the main things. The interview with Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

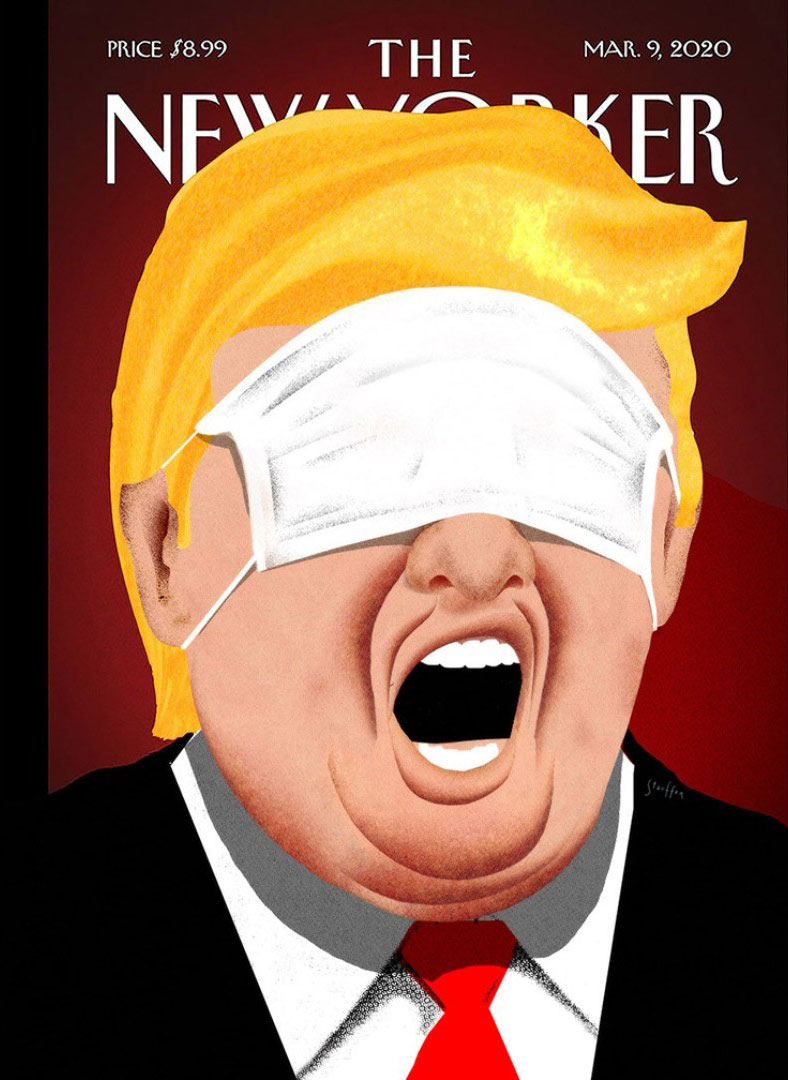

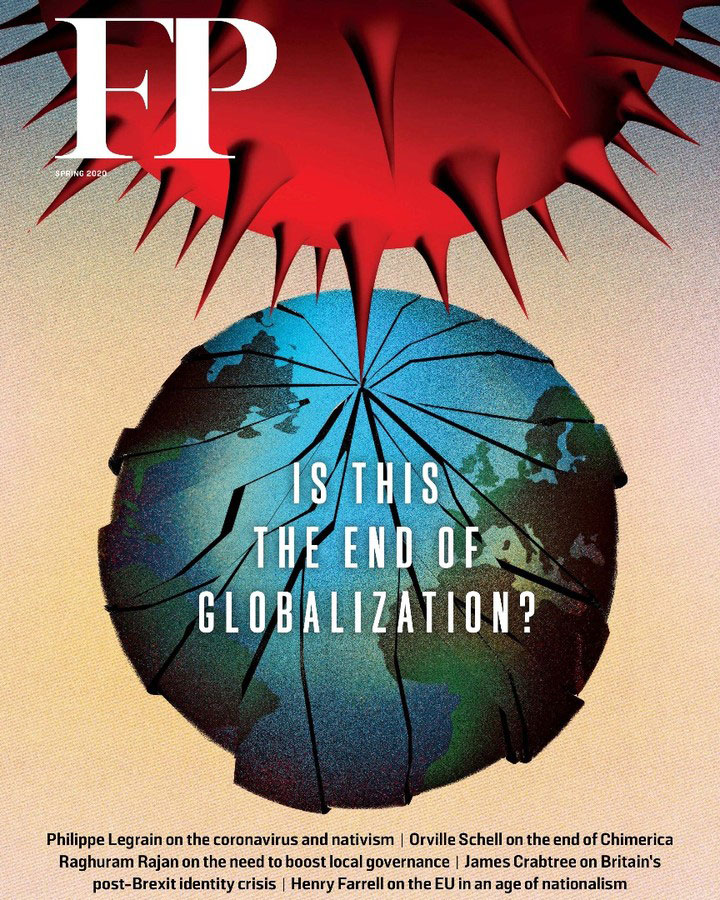

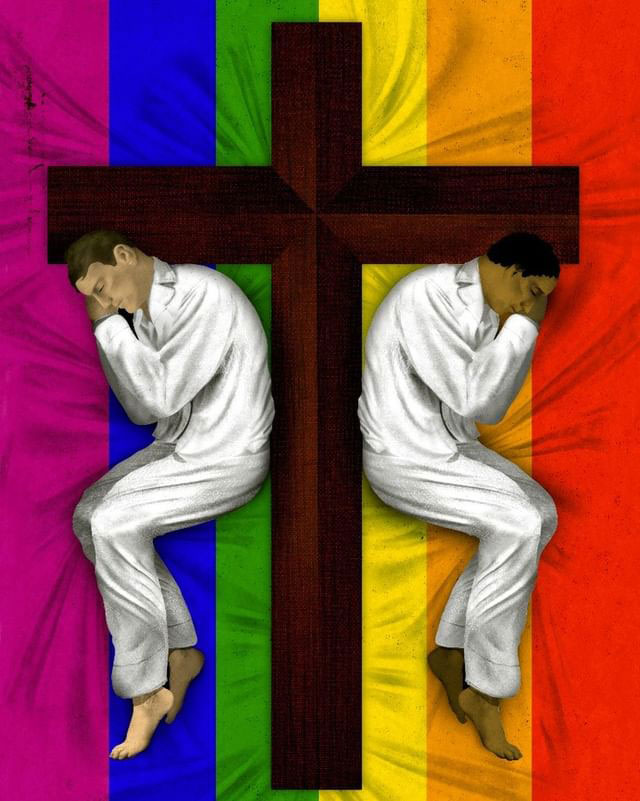

The artist from USA Brian Stauffer who devoted his all life for searching and creating graphic figures, which explain us difficult social structures and global things. His works are illustrated by the texts of the main world media: TIME, The New Yorker, The Nation, Esquire, GQ, The New York Times, Der Spiegel… Each of it has Brian’s illustration which set the pace, show attitude to nowadays and extremely impress with accuracy. We talked to the artist about his approach to creating illustrations, the hardest tasks and the war in Ukraine.

— Brian, when I scrolled your Instagram, I wonder, that it’s a chronicle of main world things and social facts of the last years. Was it your goal, to make illustrated chronicle?

— The work you see on my social media is a combination of work that is commissioned by major magazines and newspapers, and work that I feel compelled to create on my own. What has happened over the years is that my personal work that explores social issues has created a reputation for being able to handle sensitive subjects in a thoughtful way. I think it ends up being a chronicle in the process.

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

— If someone would describe one of this occasion or fact, it needs to have some minutes. But when you look at the picture — everything is clear after some seconds. Does everyone artists strive this?

— I can't speak for other artists, but I do want my images to be understood. I want to compel the viewers eye to stop and consider the messages in my images. I want the message to be there, but I want the viewer to feel like they "found it", rather than having be over-explained. Even the images of mine that are very direct and instant, should be an instant read because they feel tired or obvious. A fresh, bold, and smart image translates a level of respect that the author has for the audience. Some artists are much more interested in the mystery of the work. I personally want to make sure to leave the door open wide enough for viewers to be intrigued and to enter my world.

— Who are the most talented illustrators and what things makes them so?

— This is nearly impossible to answer. I think that on any given day, a different unknown talent is making the best work but may never have it seen.

With social media, we often see the artist with better marketing skills than artistic abilities drawing the largest audience. That following lends an air of credibility that I think can be artificial. But this has always been the case. What makes me excited about an artist's work is not how popular they are, but rather, whether their work surprises me or shows me something unexpected. I appreciate that so much in a world that often doesn't see the difference.

— Let’s imagine, that something is happening or a certain phenomenon becomes noticeable in society. You should make illustration. How do you find the right graphic shape or the story to make pictures idea?

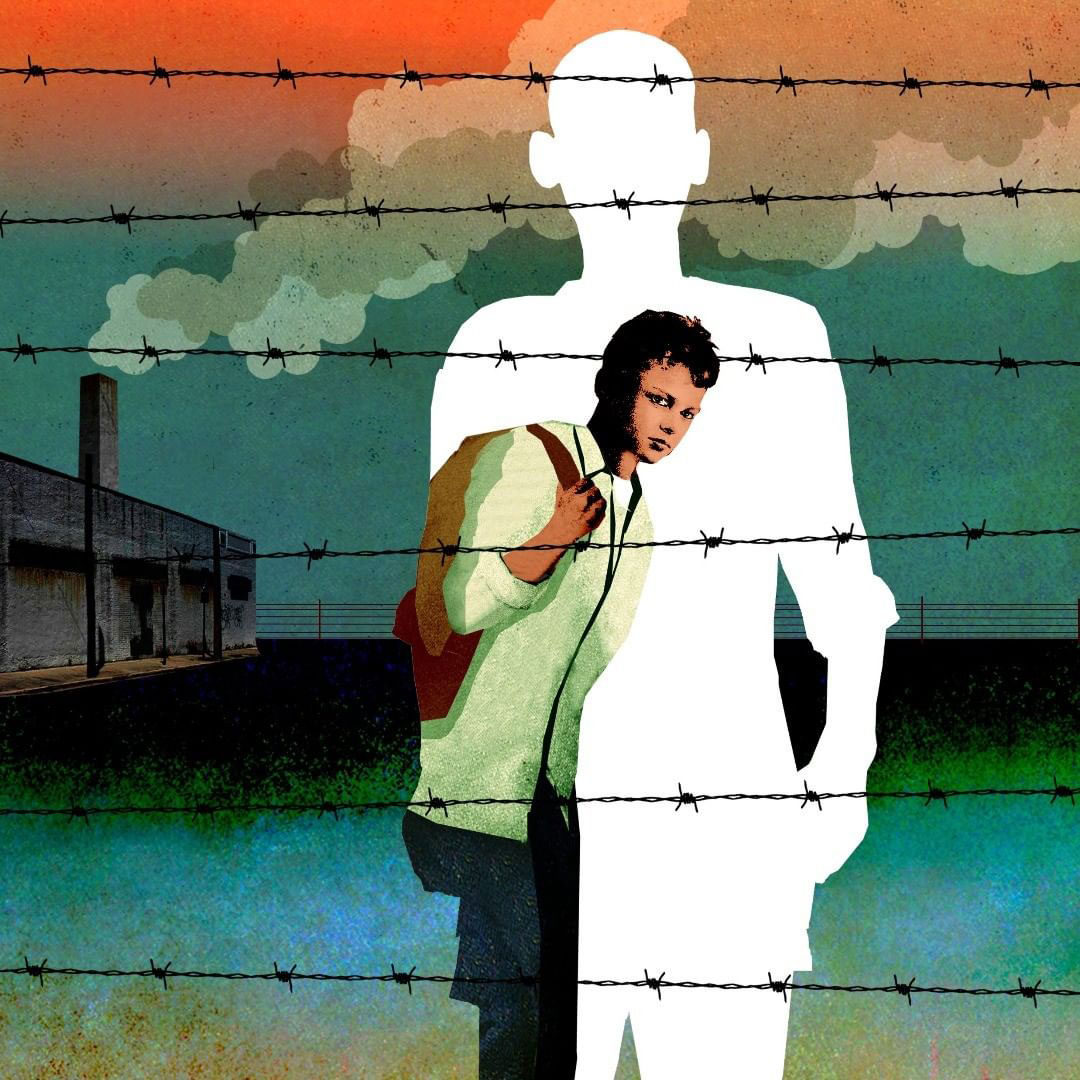

— I don't follow a specific or staged process. Some people do have these very mechanical ways of making lists of words and drawing lines and connections between those words etc to find an idea. My problem with formulas is that they produce formulaic work. So if I teach a group of students an ideation "process", there will be a large number of solutions that are identical. The best advice I can give is to surround and expose yourself to work that you love. It will force you to rise to the level of the greatness you surround yourself with. Each person's unique path through life, no matter how boring we think our upbringing may have been, gives them the potential of seeing any given topic in a unique way. The one process that I think I can share with you is one based in empathy.

Empathy is a very catchy word these days but it is nonetheless my most powerful tool. When I approach a topic, I place myself in the shoes of the people who are experiencing that topic or event. I ask myself what it would feel like and look like? What images singular images would cut through the cliches surrounding it? How would I feel if I were the subject of the artwork and I saw it on the news-stand? Would I feel like I was understood by the artist, that they represented my story well for others? Or would I think that they were trivialising my experience and sabotaging an opportunity to make others truly understand the experience of the subject?

As an example, I was given the assignment to illustrate the cover of The Boston Globe Magazine after an unusually high number of Boston Police officers committed suicide. One case involved an officer who became very depressed after a number of particularly disturbing crimes. He was found dead, by self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, in the middle of a pristine snow-covered field. There was some discussion from the editors about depicting a very graphic and violent scene. However, I put myself in the officer's shoes, imagining the loneliness and despair that he must have felt during those very last moments before he shot himself. To me, the story is about the despair, not the act itself. So I rendered him as a simple hollow outline figure, standing alone in a snow-covered field, with his pistol by his side. I wondered and worried about his family seeing any image depicting his death on the streets of Boston.

On the day it was published, I received a message from the dead officer's wife, saying that until she had seen that image, she felt that no one had really understood how much her husband had suffered.

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

— How many sketches do you make before final result?

— I usually provide about 5 sketches, but some times few less, an often many many more. I often supply 20–30 for a subject that I am connecting with particularly well.

— The war is in Ukraine. Is it possible to show all hell and tragedy in one illustration?

— No, but it can show the hell of a moment that someone is experiencing, from their view. It can put a label on the war, call it what it is. It can explain the meaning and loss behind the gruesome TicTok videos.

— How did you know about the war?

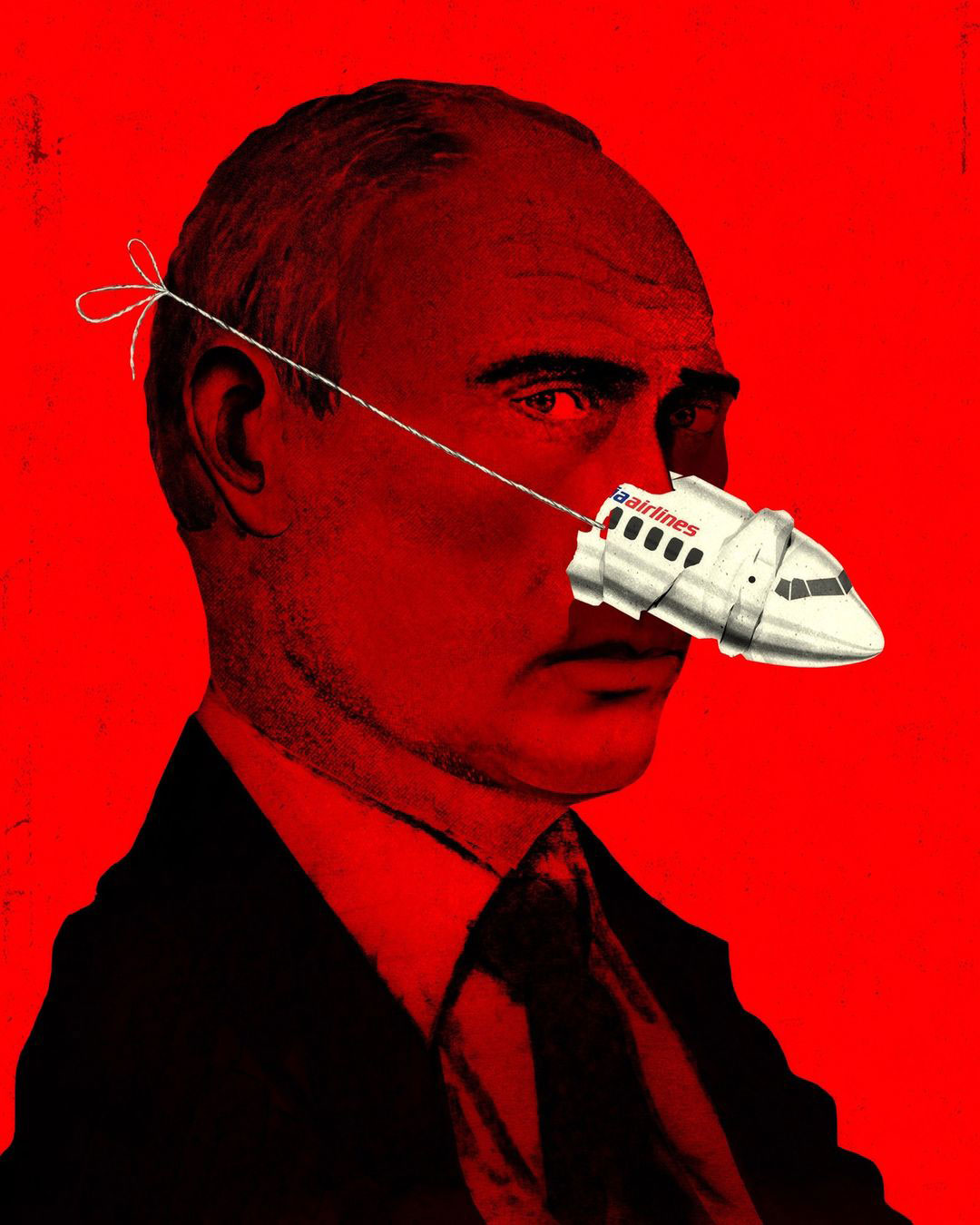

— I began to follow the conflicts in Donbas back in 2014, when the Russia loyalists shot down a Malaysian passenger jet. Putin denied any involvement but the world knew what they did. I made an image that was to run on the cover of the New Yorker. The image has a crumpled front section of the jet doubling as a Pinocchio nose.

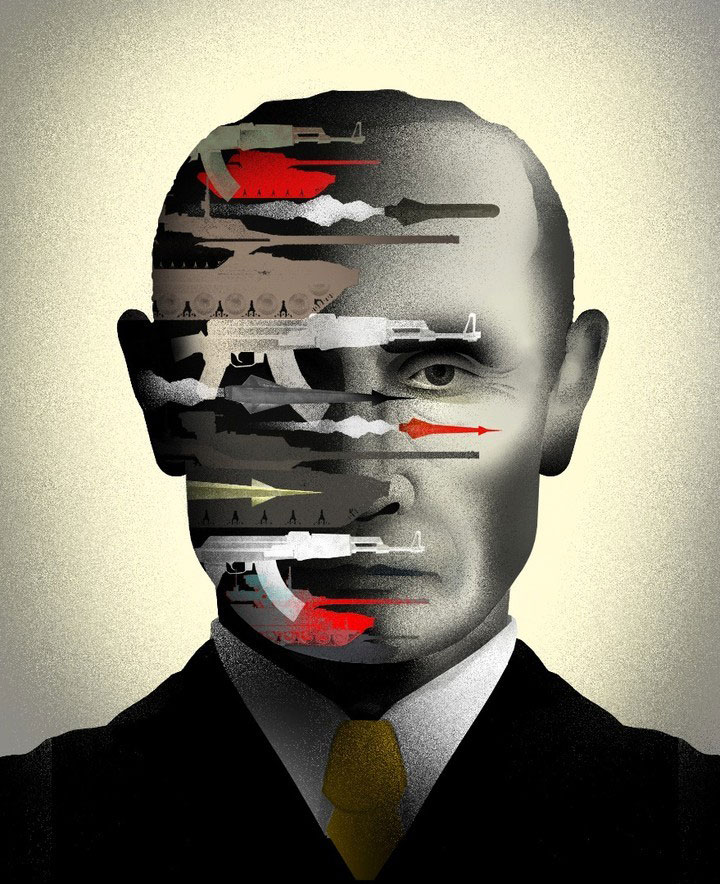

I also did a few illustration back in October 2021 as Russian troops started a on the border.

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

— In Ukraine sometimes tell: America is far away. They don’t care about you, what happen in Ukraine cause because it doesn't affect them at all. Is that true?

— It is not true. Not even close. That said, never underestimate the ability of distant countries to become distracted from the suffering in others. I think most people here see the dangers for the wider world if Russia succeeds. They also see this as a massive miscalculation by Putin. As smart as the man is, when you are surrounded by yes-men who have built their careers on telling Putin want he wants to hear, one is bound to walk into a buzz saw. I think it is comforting to many here that Putin is not an infallible machine.

— How do people in USA relate to Russia and the war witch was started in Ukraine?

— The problem we face in the USA is a desire by so many for conflicts and solutions to be described simply. In the US, a country with massively diverse populations, diverse religions, diverse wealth, and diverse ethnicities, issues facing us are anything but simple. Simple is the enemy of truth. But in a conflict a brazen as the invasion of Ukraine, even though there are many complexities to the conflict, there is a simplicity in seeing a larger force that targets civilians and lies in it’s propaganda, as being a criminal force. Life and death are very simple in contrast. It is when people try to use the war in Ukraine as some sort of political tool to gather votes or divide political parties, that things go wrong and very shallow here.

— Do you make some illustrations which contain things that happen in Ukraine now?

— I’ve done several illustrations on Ukraine which have appeared on the cover of Der Spiegel, The Nation, Rolling Stone, and others.

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

© Brian Stauffer

— Not to keep silence and not to distance yourself from war — is it brave act?

— I don't think I'm brave at all. I think it is more about wanting to know the truth of the world. It may be hard, but it's not brave. Our world has made it very easy to ignore or become numb to the suffering that is happening even as I am typing this. It's also not very good at celebrating the best of our world that is happening around us every day.

— What things help you in difficult situations not to loose the hope?

— Gratitude and perspective. I start to feel hopeless when I stop moving forward — stop finding challenges that are interesting or important enough for me to get over the fear of trying something new.

— Is it possible to make exhibition of your works in Ukraine after the end of the war?

— Yes. I've just been to Berlin for an opening of an Exhibit of 50 of my works from the past few years. The show was planned over a year ago but took on a particular relevance in recent months. It will be up until August but will then be traveling to about 10 other venues over the next 2 years. I definitely want to plan for more exhibitions.

— Finish this interview by 3 words.

— Work every day.

© Brian Stauffer