Ukrainian artist Roman Miller was born and raised in the Ukrainian city of Dovzhansk (Sverdlovsk until 2016) — a provincial town in the Luhansk region, which does not particularly contribute to the creative development of the younger generations. Usually in such cities one learns to draw from representatives of the old Soviet school, who completely dismiss something new and do not encourage creative experiments.

We talked with Roman about why he left his hometown after the occupation and how this influenced his creative development and formation.

Roman, tell us about your life and work in Luhansk region before the beginning of Russia's war against Ukraine, that is, until 2014?

I have always written naturalistic pictures about the bad aspects of human life. When the war started, I realized that I was on the right track. I began to exploit the motives of war. For example, color has not changed at all — the three primary colors of black, red, and white — have always been there. I have never done complex coloring like, for example, expressionists. The plot of my works has also not changed much. It's just that now all these plots have become reality.

My studio in Dovzhansk (Luhansk region, Ukraine) was crushed by the occupiers, considering me a spy who does not support their "new government". But several works survived.

One of my last exhibitions in Luhansk region was done in black and red tones, and even then no one there liked it: "Why did you paint like that? You have no prospects here..." — said local artists of the Soviet school. But after such a reaction, I began to work even more radically. For example, I depicted the miners without romanticizing them as martyrs. They also didn't like it very much, saying "Why do you portray heroic work like that?" But in my opinion, it is simply very difficult and there is nothing good about work in such conditions.

Where does my dad work, 2013.

Saturday (Confrontation on the Maidan), 2013.

Winter, 2014.

One day, while collecting photo material for future drawings, I was taking photos on the railway — just a railway track in one of the districts of the city. I noticed that I was being followed. They turned out to be representatives of the so-called "police of the LPR". They took me to the military headquarters and began to ask what I had photographed and to find out if I was a Ukrainian saboteur.

I came out of that military checkpoint a few hours later after checking all my photos in my camera and contacts in my phone. They had no complaints, except that they did not like my notebook with sketches of the "Image of the Enemy" series — in which I depicted the "new government of Luhansk region". But miraculously they let me go and told me to come back the next day.

I understood that I had to leave the city. The next morning, I packed my backpack and went to Kharkiv.

How did such life changes affect creativity?

Both positively and negatively. For a while I stopped drawing altogether. After moving, it was necessary to find housing and get a job. Because creativity as such does not bring money, it is necessary to work additionally. And it was simply necessary to "digest" all these changes as they happened.

But when the time came and I felt the need to say something, I began to have completely different works than before. I began to work on simplification, with a minimalist palette and began to increase the actualization of my works. And now I continue to do it.

What exactly are you doing now?

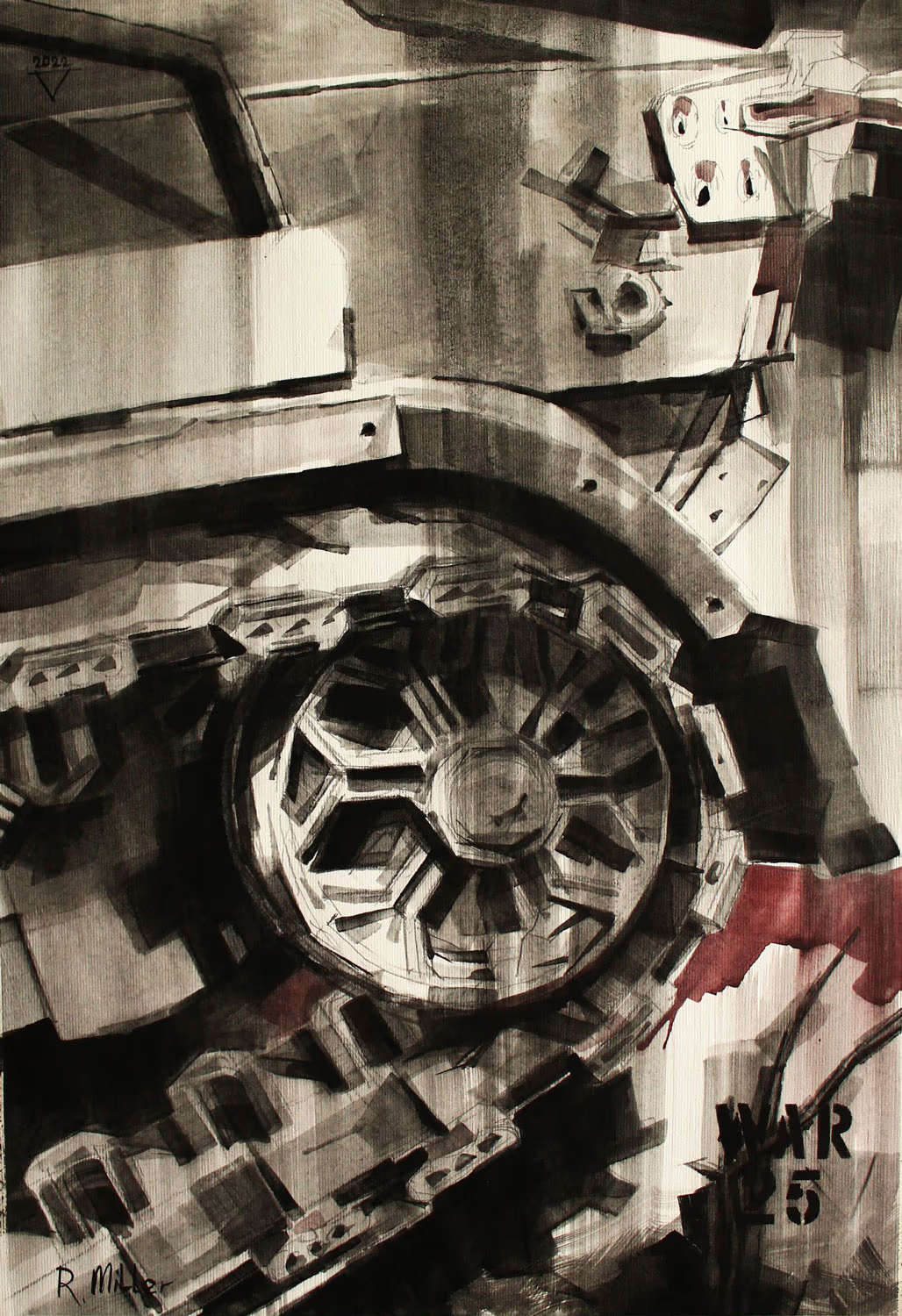

About a year ago, I got acquainted with Pynchon's book Rainbow of Attraction. This is a very thick book, but, in a word, about nothing. That is, you read and do not understand what is happening there. But one American artist created an illustration for each page of this book. 900 pages - 900 illustrations. Because of this, he became quite famous. He gave me the idea of creating an illustration for each day of the war. This is one of the projects — called War — that I'm currently working on.

How is life in Dnipro for you now?

I teach painting and drawing at the university, conduct master classes. Well, I am engaged in creativity.

Do you remember the life that was in Luhansk Region?

Well, of course, melancholy happens. But the further it is from 2014, the less and less you remember. It is impossible to say that there was such a good life there. It was okay, but it's a very small mining town. The only thing that young people had fun with was alcohol. There was almost no culture or creativity. All more or less working artists were graduates of the Soviet school. That is, their exhibitions are complete social realism, and of average quality. And it was almost impossible to create an exhibition there, even a modest one — just to show friends and other artists their work. This, by the way, was also the case in Dnipro — a very prejudiced attitude towards works that reflect, for example, the division of society or other shortcomings.

There is one work that I wanted to exhibit. On it, a homeless person is lying on a concrete slab, with a bottle of cola next to it. Summer, a person rests. This is a common plot that can be seen in the Dnipro. And they did not want to take such a picture from me. And about six months later, I see that they have a picture of homeless people rummaging through the garbage. I reminded the organizers about my painting and asked why they took this painting, but they didn't want mine. And they answered me: "This is a member of the Union of Artists!"

So we are running away from everything Soviet, and it still sometimes catches up with us?

Perhaps this is an isolated case. But it still works here and there. Of course, I understand that my paintings can sometimes shock, but I do not set such a goal. The main thing is to understand the picture.

Sometimes Soviet art connoisseurs like to say: "Would you hang this in your home?"

Yes, I had such an acquaintance!

How does an artist earn money today?

Well, it is still difficult for me to earn money with one creativity. I earn more by lecturing and teaching. But today, my creativity at least feeds itself. That is, I buy paper, canvas, blanks, brushes, paint, do several works, sell, buy materials again. It's already good, as far as I'm concerned. Because there was a period when I had to choose between buying food or paint brushes.

The War series. How do you select stories, subjects for paintings?

One who is engaged in visual arts, thinks in images. From the beginning, there should be an image that attracts the author's attention and that can be aestheticized. Then you start to "impose" some layers of subtext on it. To draw something out of order, you need to concentrate on this idea. Find an approach to reflect this or that event. So that it is not a redrawing.

Now I do not include only Ukrainian tragedies in the series, but Russian ones as well. For example, their intellectual tragedies. Now the works in the series are becoming more philosophical, and the first ones were "on the heels" of events.

I think that when the war is over, I will make the best works of the series in large formats.

What is the role of art during the war?

The creation must be a reflection of the reality in which it is created. Even if mythological creatures are depicted, they were still dressed or painted with attributes characteristic of that era. And so now. Artists should create something relevant and narrative. And this narrative should be anti-war at the same time, so that future generations understand that war is a tragedy. Always a tragedy. Such works can be called somewhere and immediately.

After the Second World War, a lot of films were shot, books were written, and theater productions were made about the horrors of war. And quite a number of such anti-war things, including talented ones, were created in modern Russia. But why didn't it all work?

It is necessary to exclude romanticization. In Germany there are monuments to the Second World War and they are really scary. And in the Ryadian Union, they created, for example, some kind of abstract warrior. Invented, to which a lot of exploits are attributed. And years passed, everyone stopped understanding who it was. And with the Soviet love for rewriting history, no one understands where the truth is and where lies. They made such a big fairy tale about the war, and if you look at it that way, it's not so bad.