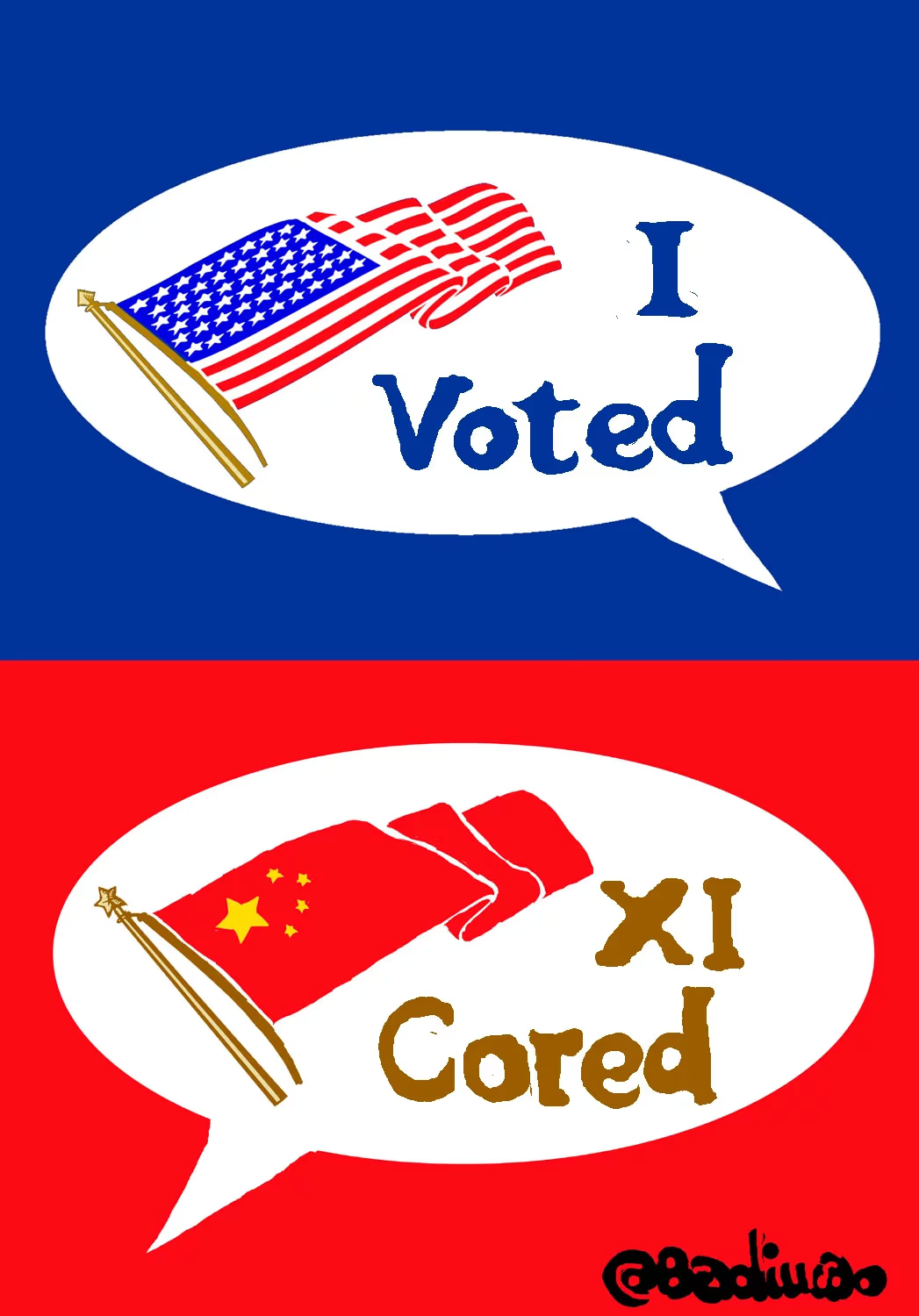

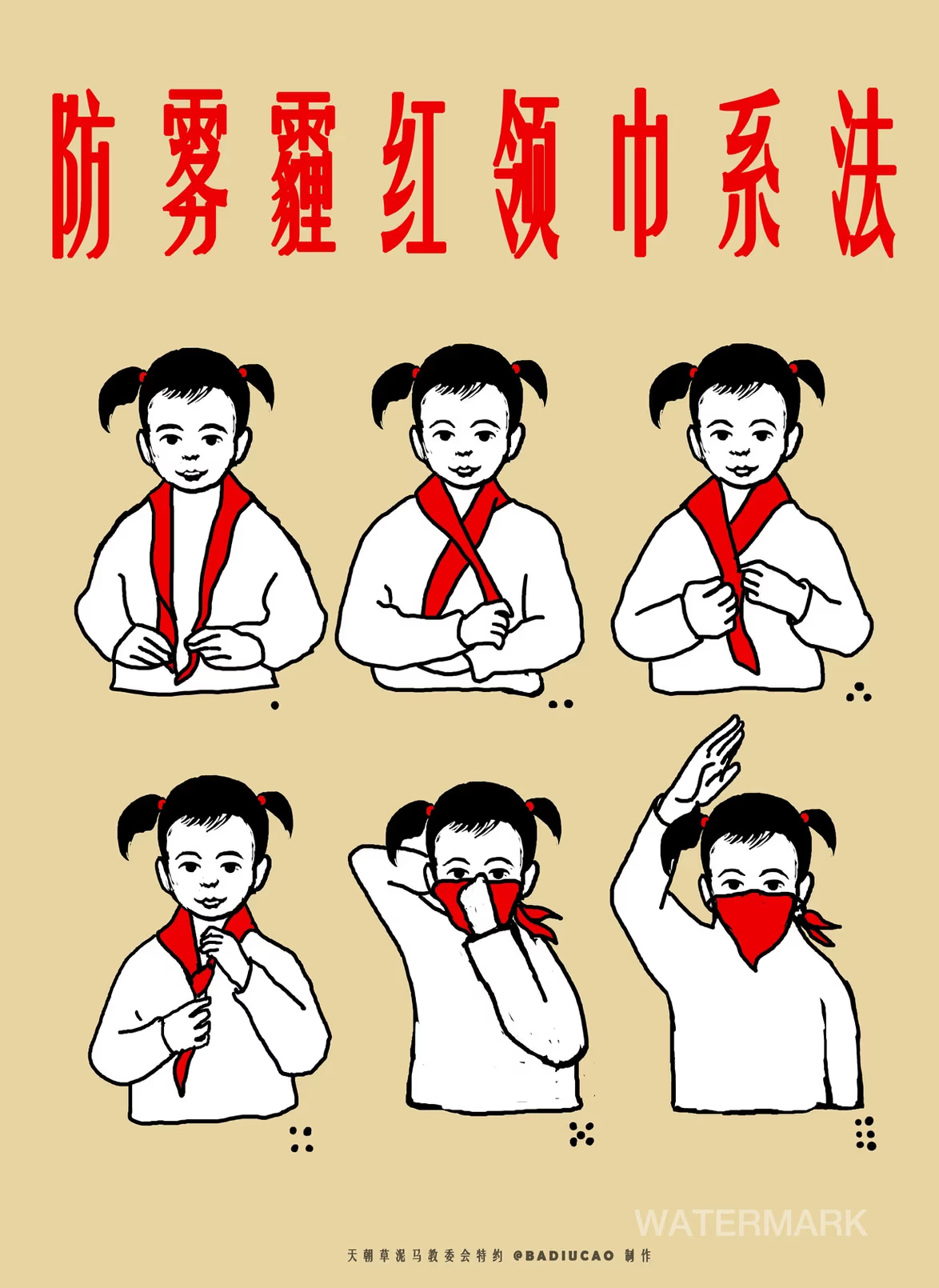

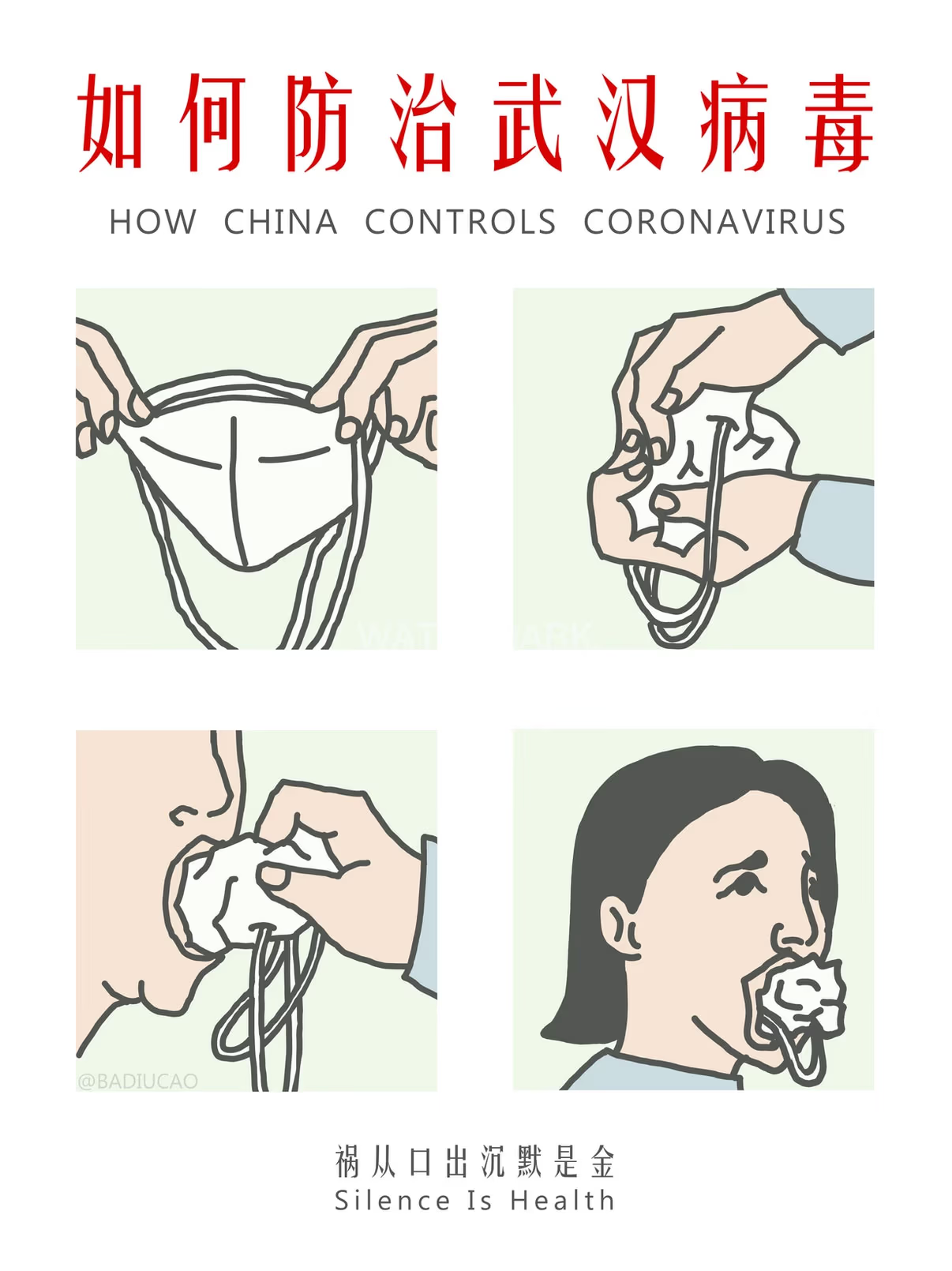

Intolerance toward freedom of thought and expression, xenophobia, and censorship are hallmarks of any authoritarian regime. Such states skillfully manipulate public opinion, artificially turning dissenters into outcasts who oppose the "official position". Various forms of repression are employed: public shaming, job dismissals, intimidation of family members, and imprisonment. Over a decade ago, a Chinese artist known by the pseudonym Badiucao was forced to leave his native Shanghai to remain free and express his views on events in China without censorship. Despite its developed economy, the situation with freedom of speech in China remains dire. For years, Badiucao has openly spoken out against the restrictions on opposition voices, internet censorship, distortions of political events, and propaganda. His works are banned in China, his exhibitions in Europe have been targeted for cancellation by Chinese embassies, and he cannot return to Shanghai without facing immediate arrest. In this interview, we discuss Badiucao’s exposure of Chinese propaganda and the country’s role in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

On your Instagram, it says you’re a 'Chinese artist hated by the Chinese government'. How did that come about?

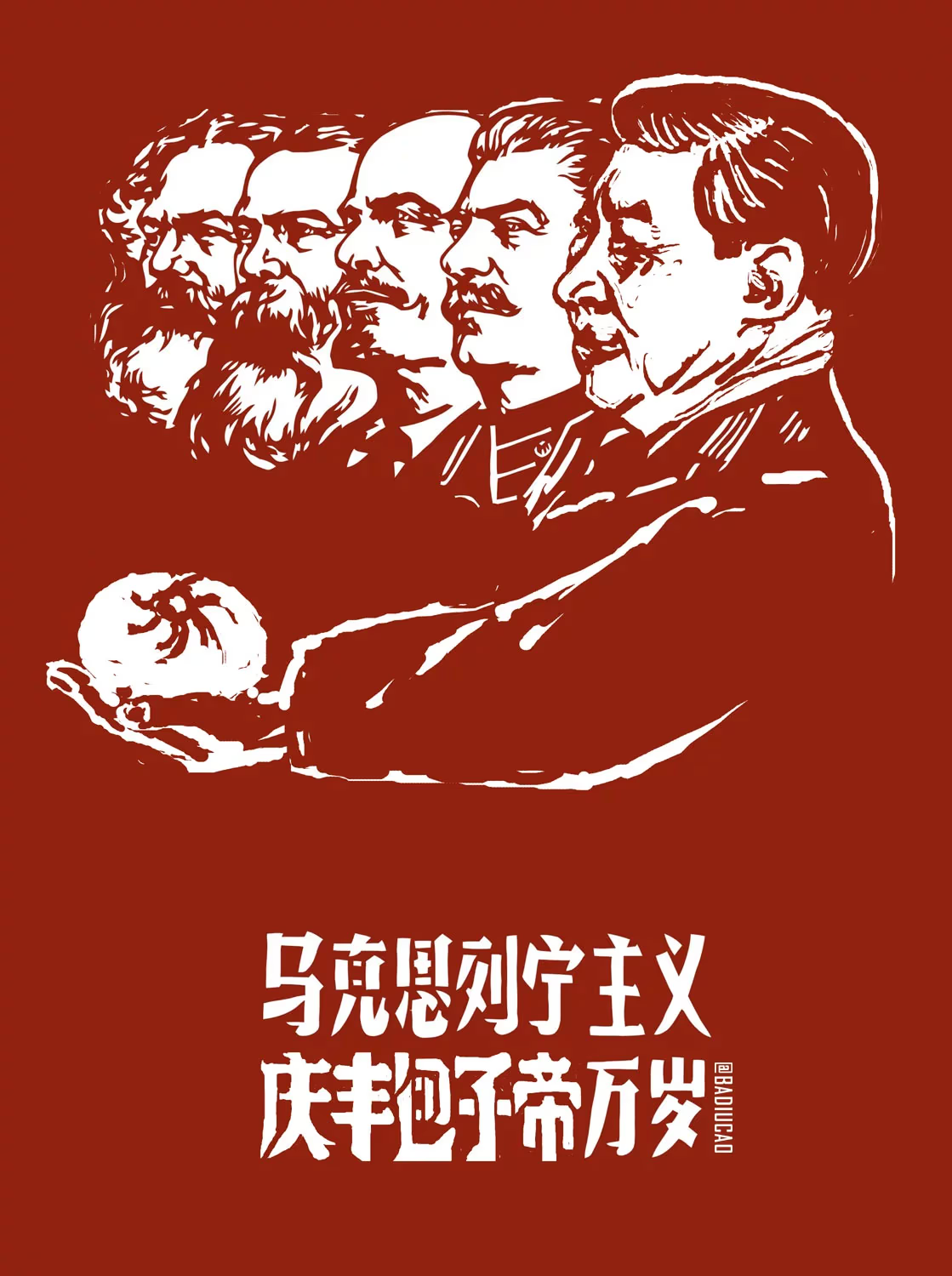

Well, I think the Chinese government is authoritarian and illegitimate; it doesn’t tolerate criticism. As an artist, I dedicate most of my work to addressing issues in China and its ruling dynasty—this makes me their number one target among artists. The ruling elites adhere to a single model of governing the country and dislike change. At their core, they oppose free creativity and innovation, which are difficult to control.

In recent years, the Chinese government has threatened me multiple times through its embassies in Europe. They’ve even demanded the closure of my exhibitions.

You’ve been living in Australia for over 10 years, but you were born in Shanghai. What do you remember about your childhood there?

Shanghai is a very civilized city compared to most Chinese cities. It’s home to 20 million people, highly developed, and Westernized, with countless skyscrapers and universities. It’s a great place to live—until you encounter politics.

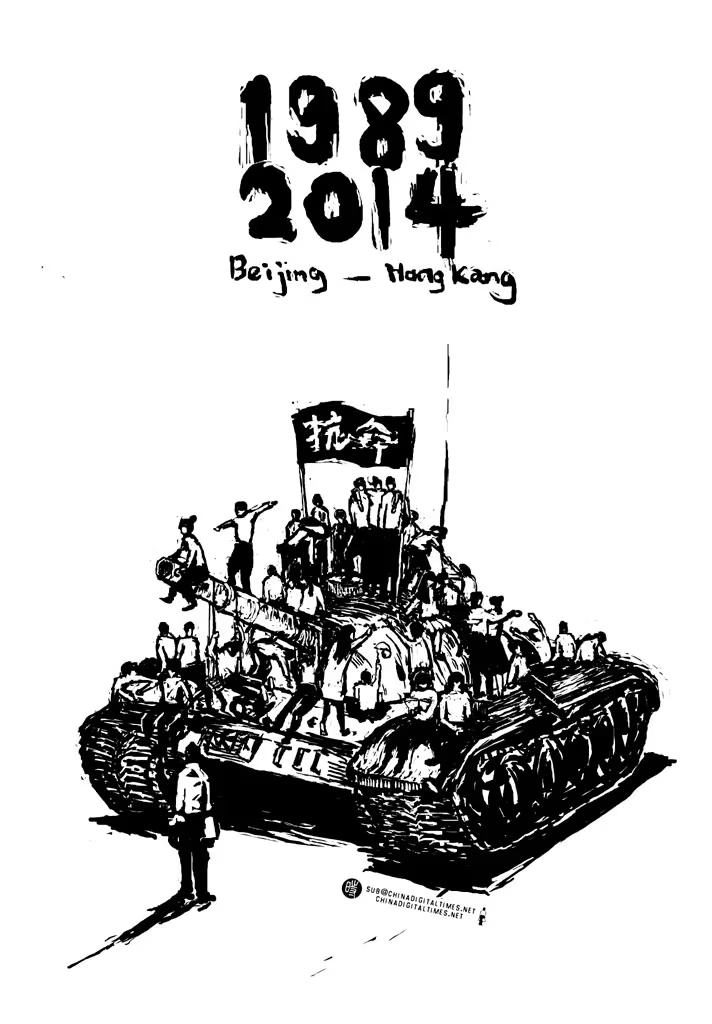

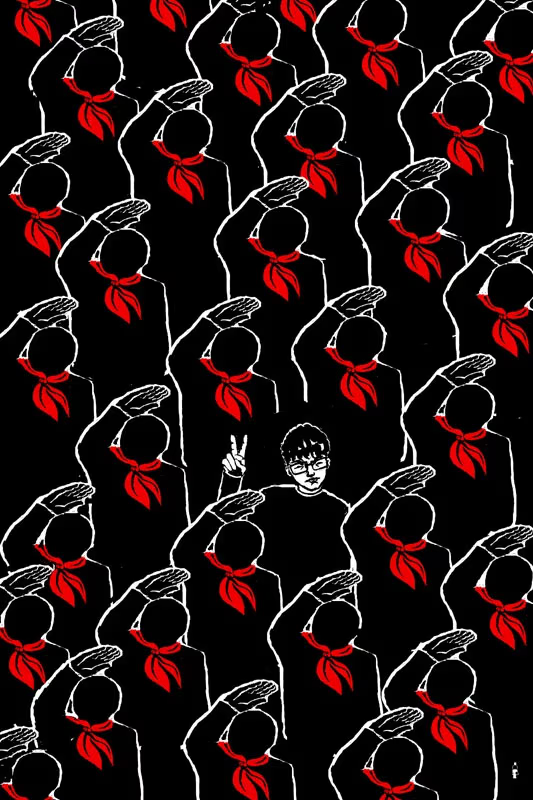

I remember how, from early school years, we were raised in the spirit of communism and endlessly told about the Party. When you’re seven years old, it drives you crazy! In 1997, when Deng Xiaoping died, it was forbidden to smile at school that day. My friends and I couldn’t understand why we were supposed to refer to this man as "Grandpa", as if he were a family member or relative. Only when I got older did I realize it was all manipulation.

How did your family react to your decision to leave China?

They supported my decision. I see myself as continuing the fight of my ancestors. My grandparents were the first in our family to experience repression for criticizing the Chinese regime back in the 1950s. My father told me about their experiences and didn’t want me to follow the same path. That’s why I started my work as an anonymous artist. However, in 2019, my identity was revealed, and my family in Shanghai had to deal with the police.

Despite their support, leaving wasn’t easy. But it was necessary to realize my potential and gain complete freedom.

What was your first work about?

In 2011, a collision between two high-speed passenger trains occurred in Wenzhou. It became a major issue for the government since China was selling the technology for these trains to Europe and the U.S. Many people died, and even more were injured, but the Chinese government did everything possible to suppress information about the tragedy and minimize its negative impact on the country’s transportation industry.

Nevertheless, the accident was widely covered in the media and online. At the time, I was already living in Australia, and I felt the urge to speak out. That’s how I created my first political cartoon.

Your exhibition MADe IN CHINA is currently on display in Prague. Can you tell us about its concept and what visitors can see there?

The exhibition is a collection of my recent works, some of which were previously shown in Italy. However, for the Prague exhibition, I added six new pieces about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Living away from China, I’ve learned how to portray politics through humor.

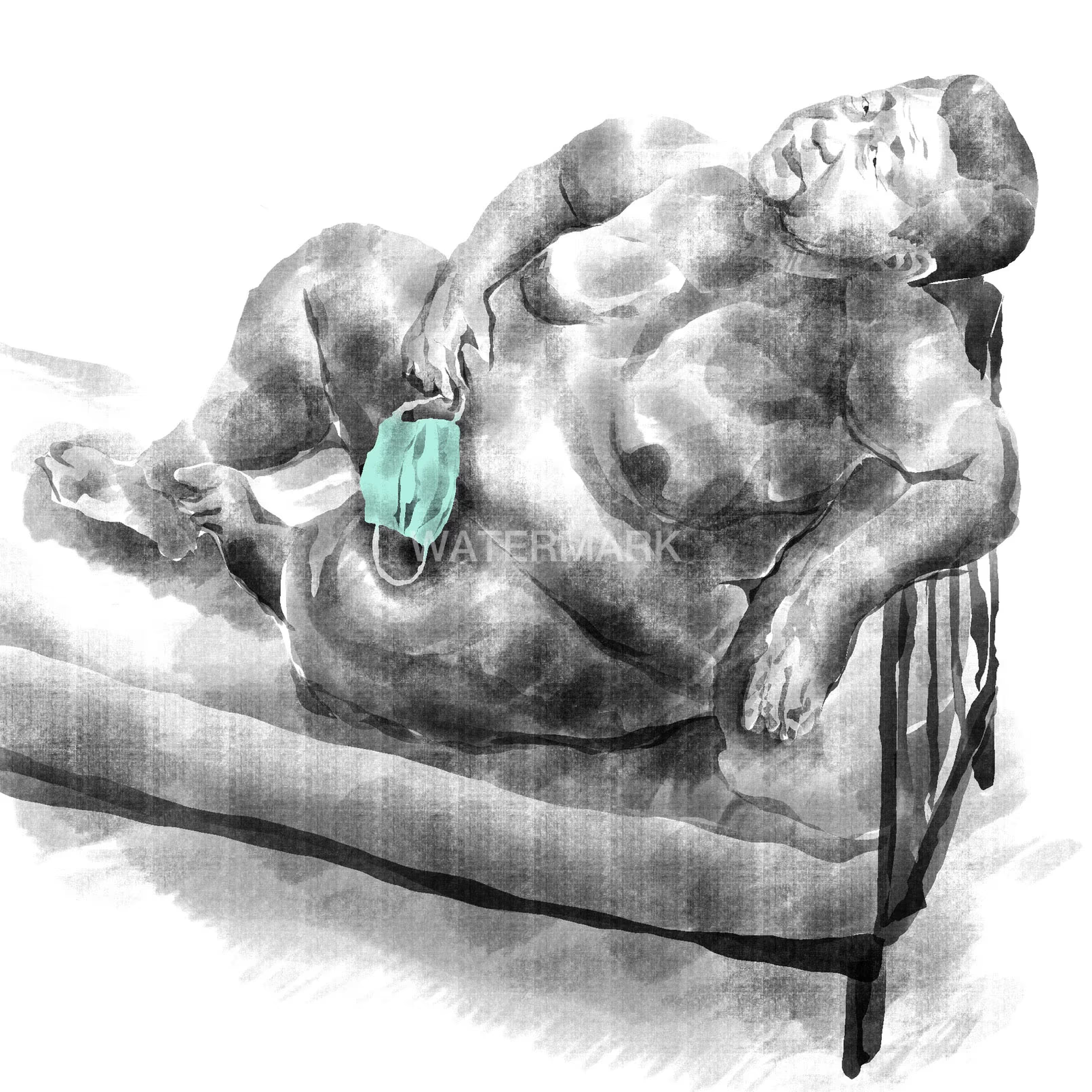

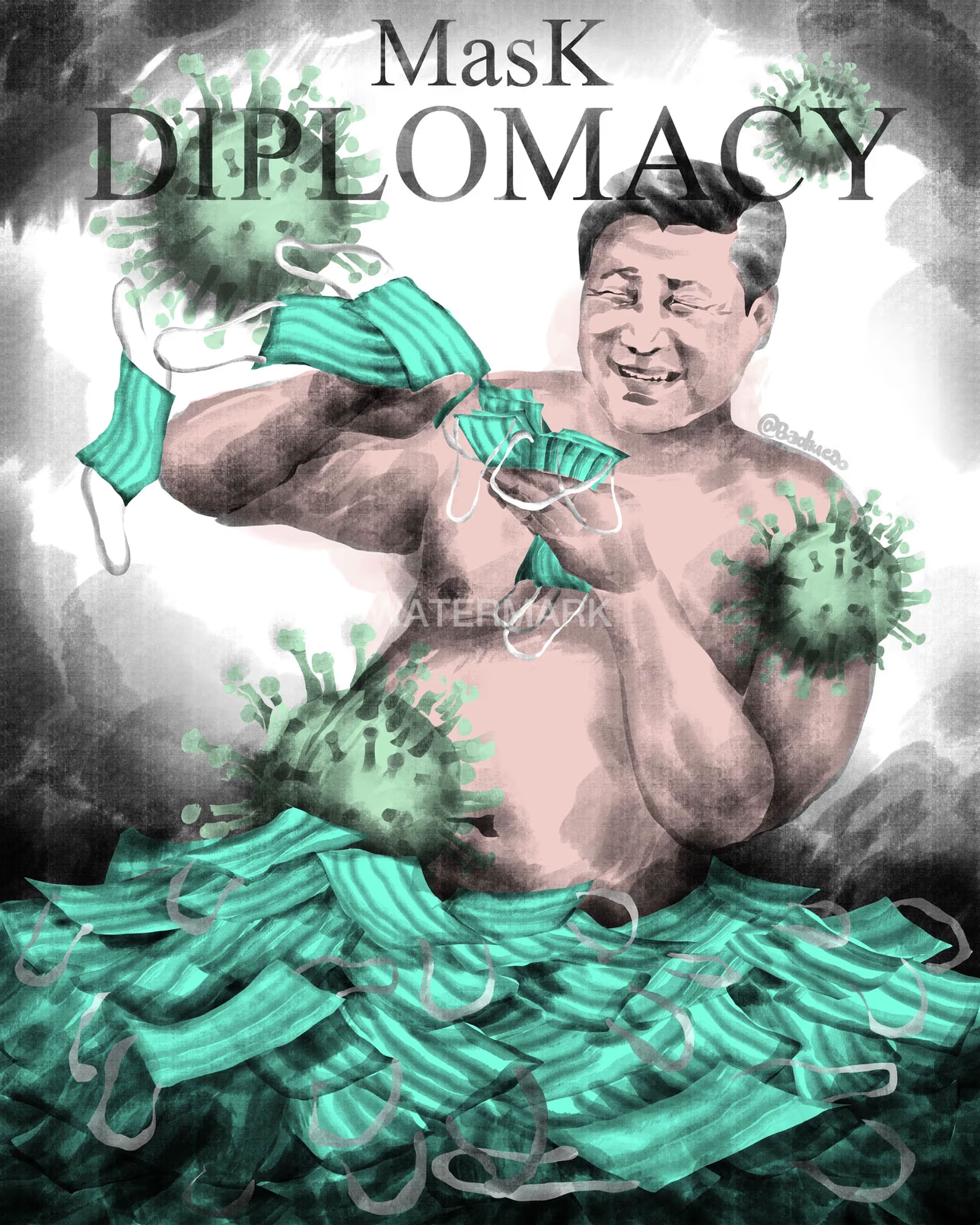

A significant part of the exhibition is dedicated to COVID-19, which originated in China, and the government’s responsibility for losing control over it. Eight doctors who tried to warn the public about the danger were arrested and punished.

There are also pieces about prison torture, which, unfortunately, remains a routine practice in China.

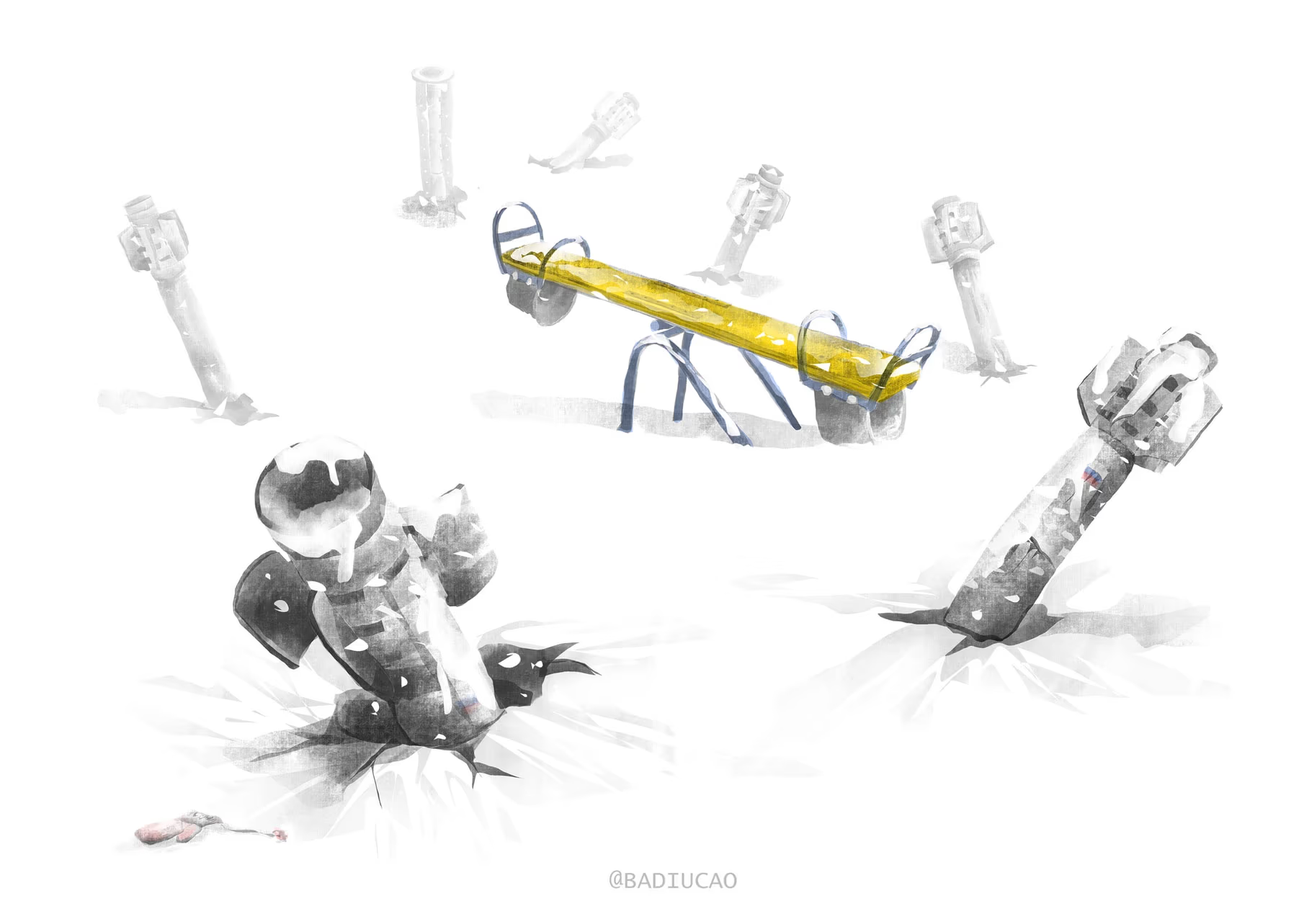

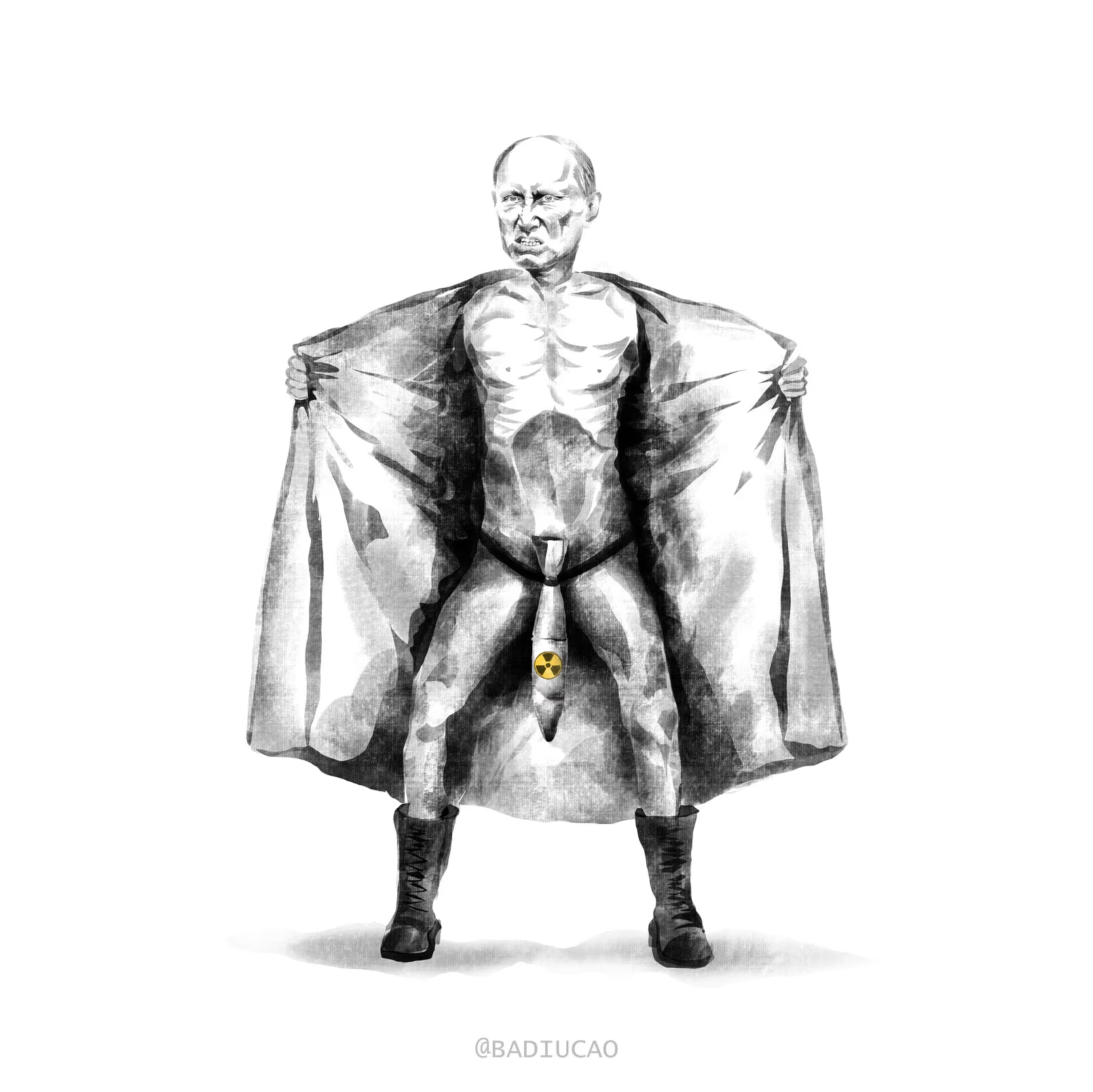

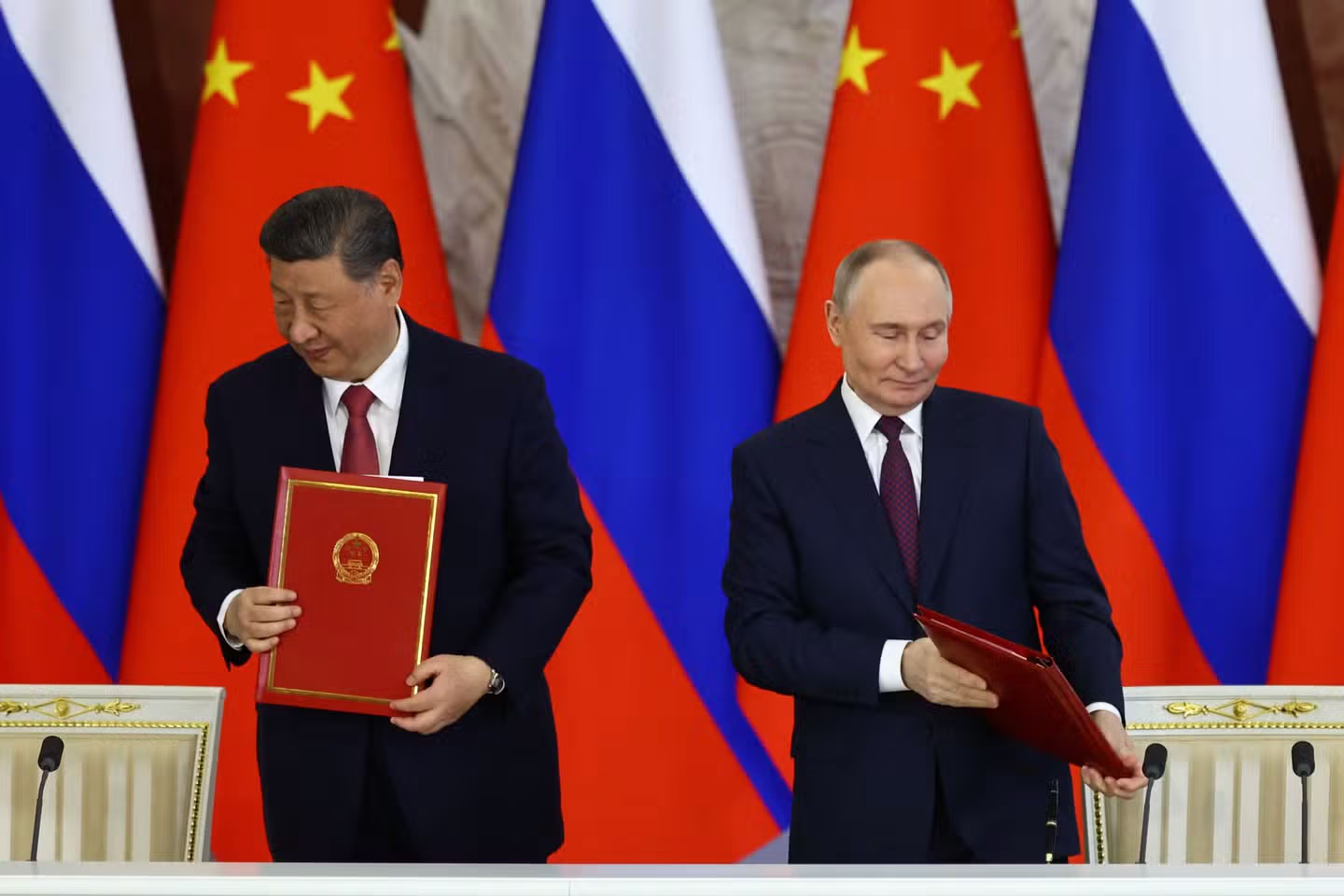

The most pressing theme of the exhibition is Russia’s war against Ukraine. I’ve presented six works that are also sold as NFTs. The proceeds from these sales go to those in need in Ukraine. There’s also a large portrait—a fusion of Xi Jinping’s and Vladimir Putin’s faces—symbolizing how the Chinese leader covertly supports Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, including financial and propaganda backing. Personally, I’m ashamed of my country’s actions in this regard.

Will it be possible to see your exhibition in Ukraine after the war?

I would really love that!

I want to thank you for supporting Ukraine, especially through your NFT project Seeds in the Pockets. How do you think China views Russia’s war in Ukraine? Whose side is it on, and can Russia rely on China for support?

In my opinion, we need to distinguish between the Chinese government, led by Xi Jinping, and the Chinese people. The Chinese government knew about the invasion before it happened. Xi Jinping allows Putin to speak about the friendship between China and Russia while Russia wages an aggressive war. Official Chinese media avoid using the word 'war' when covering events in Ukraine. Additionally, there’s tacit financial support. It’s clear that Xi Jinping supports Putin.

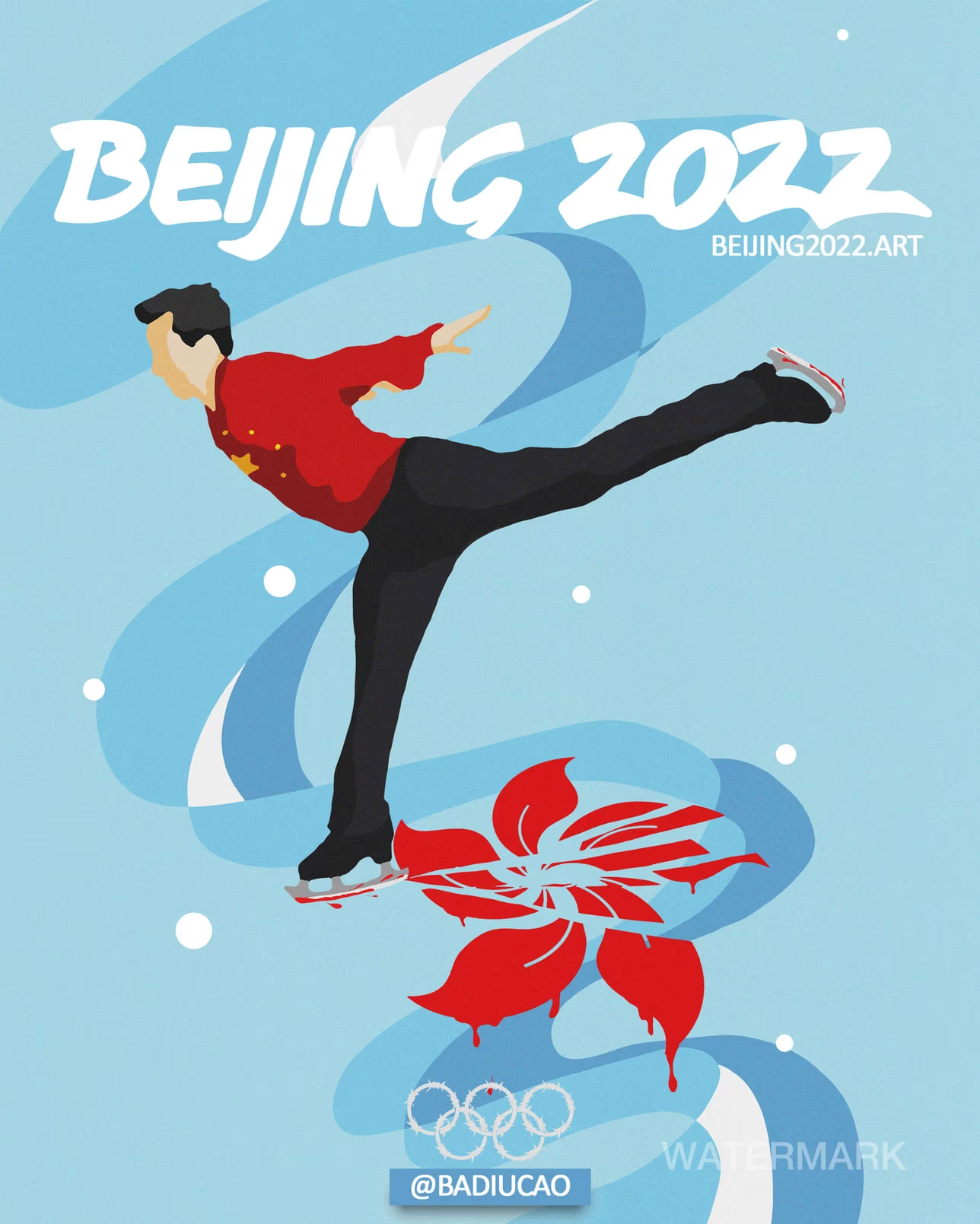

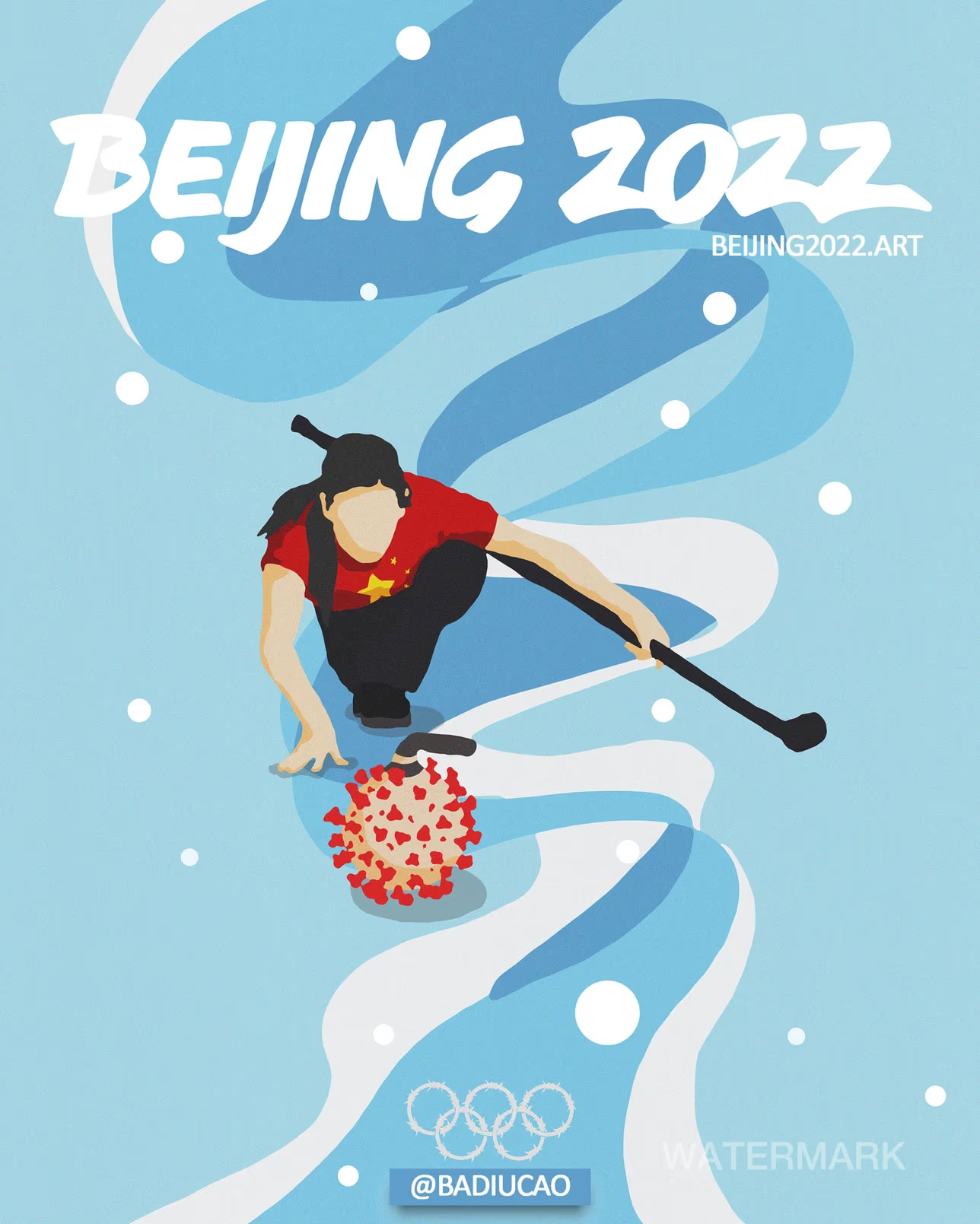

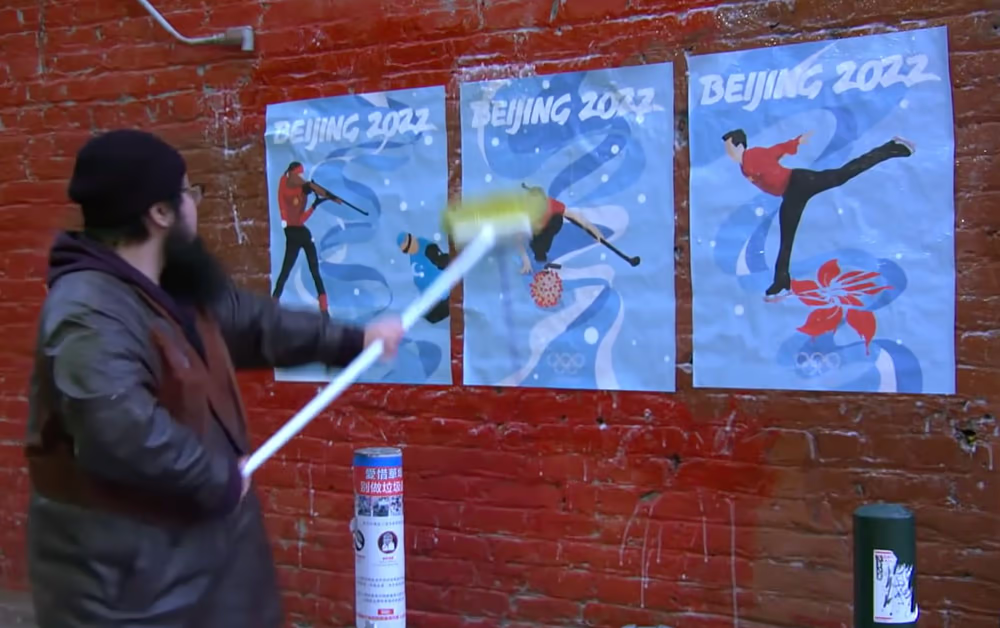

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began right after the 2022 Olympics, which were held in China. You dedicated an entire series of works to the event. Can you tell us how you developed that project?

People are used to enjoying the Olympics. But to me, it’s a kind of confrontation between countries, only without weapons and violence—a peaceful alternative to war. Instead of killing each other, nations compete to see who is faster, stronger, or can go farther. That’s the spirit of the Olympics, in my opinion.

I wanted to combine China’s political issues with the games and humor to show the conditions and circumstances under which these games were actually held. It took me a long time to find the right approach, but in the end, I was satisfied with the solution.

Despite censorship, I assume your works can still be seen in China. Do you receive any feedback or comments from people living there?

If you visualize it, censorship is like a rock wall—heavy and seemingly impenetrable. Art, on the other hand, is like water droplets that find their way through cracks in the stones. There are people who hear and understand my messages. They use VPNs, download my works (I always upload them in high quality), and share them. It’s a way to show people what freedom is and what it looks like. People need to see the difference.

Are there many people in China who share your views? Why don’t they want to leave?

That’s the most difficult question. Because of the censorship of the Chinese regime, it’s often hard to understand what the dominant public opinion in the country is. People hold many different opinions about the government. I know that many disagree with its actions, and I believe that one day China will change.

When will you be able to return to China?

(Laughs) I can go back anytime. But I’m afraid that as soon as I do, the only place I’ll be allowed to stay will be a prison cell.

I hope that someday China will become more democratic, and I’ll be able to return and remain safe.

Made in China

Beijing Is Trying to Erase Tiananmen—Now Even Abroad

The U.S. and Taiwan Say: The World Will Not Forget June 4, 1989

An Alliance Doomed to Asymmetry

Why Strategic Rapprochement With China Is Leading to a New Russian Dependency

China Rehearses a Blockade of Taiwan

Beijing is Pressuring the Island Through Drills, Laws, and Economic Leverage, Aiming to Break Its Resistance by 2027—Before the U.S. Can Intervene

China Prepares for a Prolonged Trade War

Beijing Builds Economic Resilience and Bets on Domestic Demand

China Introduces Digital ID for Internet Users

The System Will Strengthen State Control Over Online Activity—and Could End Anonymity for Good