On July 17, Financial Times published an article titled "Volodymyr Zelenskyy accused of authoritarian slide after anti-corruption raids", detailing recent actions by the Ukrainian government that have raised concerns both domestically and abroad. The trigger was a series of searches targeting anti-corruption activist Vitaliy Shabunin and former infrastructure minister Oleksandr Kubrakov, carried out in violation of procedural norms.

Against this backdrop, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy replaced the prime minister, tightened control over anti-corruption institutions, and refused to approve an independent candidate to lead the Bureau of Economic Security. Critics say these steps point to a broader crackdown on dissent and the dismantling of democratic checks and balances.

Anti-corruption raids targeting prominent public figures, along with reshuffles that consolidate power among presidential loyalists, have triggered accusations that Zelenskyy’s administration is drifting toward authoritarianism. Increasingly, observers warn that the president and his inner circle are using the powers granted under martial law to silence critics, pressure civil society, and tighten personal control.

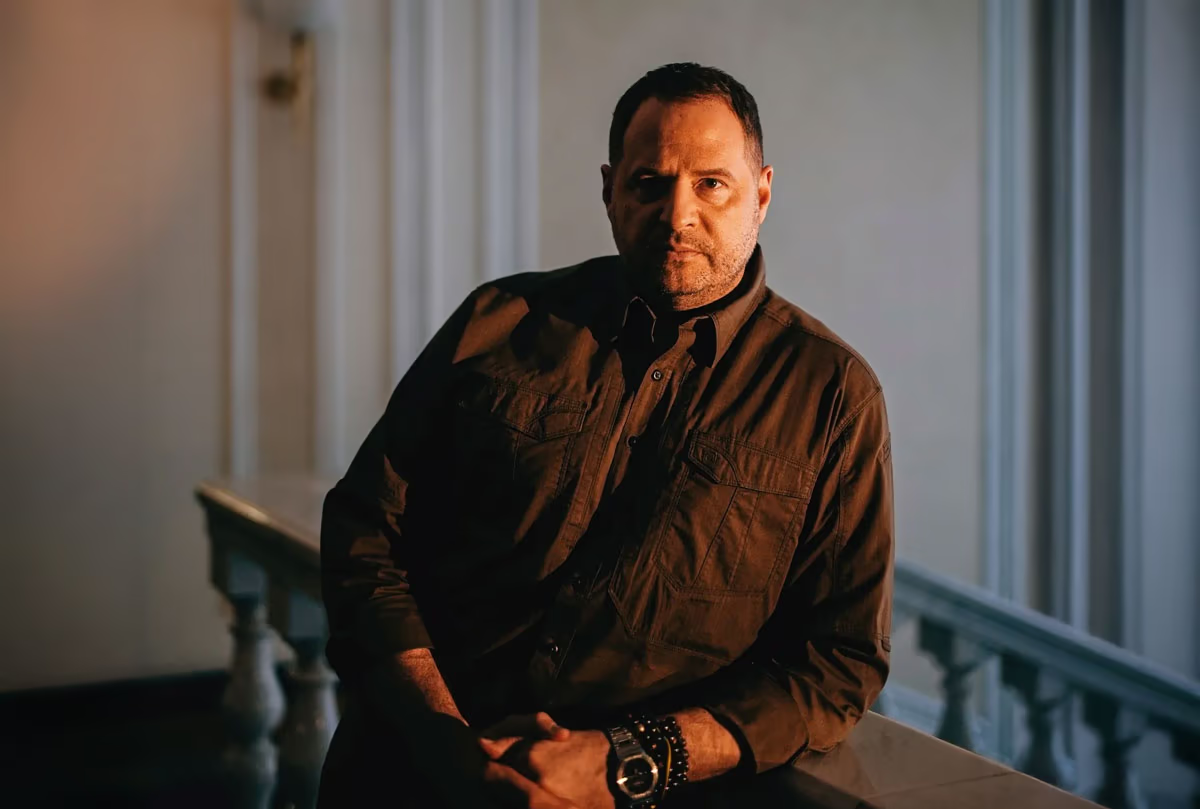

Tensions escalated on July 12, when armed officers from the State Bureau of Investigation raided the home of Kharkiv-based activist and anti-corruption advocate Vitaliy Shabunin. His phones, laptops, and tablets were seized. Almost simultaneously, investigators conducted a search at the home of former infrastructure minister Oleksandr Kubrakov in Kyiv. Both men said the actions were politically motivated: no warrants were presented, and lawyers were not allowed to be present.

Shabunin told the Financial Times that the raids were intended as intimidation: "If they can go after me—a person under media scrutiny and with public support—then they can go after anyone." He believes the real targets are two groups: activists and journalists, as well as servicemen—since the charges against him stem from his time in Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces. His lawyer argues the case is fabricated and meant to discredit him.

Despite their individual contexts, critics see the cases against Shabunin and Kubrakov as part of a politically driven campaign. Civil society groups and opposition lawmakers have described the events as a coordinated attempt to suppress dissent. MP Oleksandra Ustinova called it a "Russian-style scenario" designed to divide society. Leading Ukrainian media were equally outspoken: Ukrainska Pravda warned of "the first but confident steps by Zelenskyy toward corrupt authoritarianism," while the Kyiv Independent noted that a crackdown of this scale on a high-profile anti-corruption figure could not have happened without the president’s approval.

At Home

The Prosecutor General Gets It All

How the Law Subordinating Anti-Corruption Agencies Became a Turning Point for Ukrainian Democracy

What Some Would Call Propaganda

The Economist Raises Concerns About Authoritarian Drift in Ukraine

A Power Struggle at the Expense of Defense

At a Critical Moment in the War, the State Is Focused on Reallocating Authority

Government interference in the internal procedures of anti-corruption agencies has also sparked a sharp backlash. The cabinet refused to appoint Oleksandr Tsyvinsky—who was selected through an independent process—as head of the Bureau of Economic Security. According to MP Anastasia Radina, chair of the parliamentary anti-corruption committee, the cabinet had no authority to block the appointment.

In parallel, Zelenskyy replaced the prime minister. Yuliia Svyrydenko, a close ally of presidential chief of staff Andriy Yermak, took over from Denys Shmyhal, who had led the government since 2020. The reshuffle came amid a worsening situation on the front lines, Ukraine’s ongoing push to secure continued U.S. support, and efforts to reboot the executive team.

Kubrakov’s case concerns an alleged scheme to procure Belarusian fertilizers worth $350,000. The former minister denies any involvement and says the investigation is retaliation for his attempts to expose corruption by First Deputy Prime Minister Oleksiy Chernyshov, a key figure in Zelenskyy’s inner circle. In mid-July, Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau formally charged Chernyshov in a separate case involving a $24 million land fraud. Shabunin has claimed that the criminal proceedings against him and Kubrakov are a response to the broader efforts of the anti-corruption community, including their attempt to block a bill that would have granted amnesty to defense contractors implicated in graft.

According to Daria Kaleniuk, executive director of AntAC, the case against Shabunin is an attempt to exert pressure through the use of mobilization laws and military secrecy. She believes the administration is counting on the West—preoccupied with other crises—not to pay sufficient attention to what is happening.

That assumption may not be unfounded: despite previous public warnings from the G7, this time Western embassies in Kyiv have refrained from making direct comments—even in response to the raids targeting Shabunin and Kubrakov. One ambassador admitted, "It is very difficult to criticize Ukraine right now," given the intensity of Russian aggression. Others point to the delicate balance between offering support and ensuring reform oversight.

The resignation of U.S. Ambassador Bridget Brink in April, following disagreements with the Trump administration, and the absence of a permanent mission head have only deepened the sense of uncertainty. One Western diplomat noted that Ukrainians have sensed a shift in Washington’s approach: the rule of law and good governance no longer seem to be top priorities.

"If the institutions designed to provide checks and balances are turned into tools of pressure, Ukraine risks losing the democratic core it has fought for since 2014," Kaleniuk concluded.