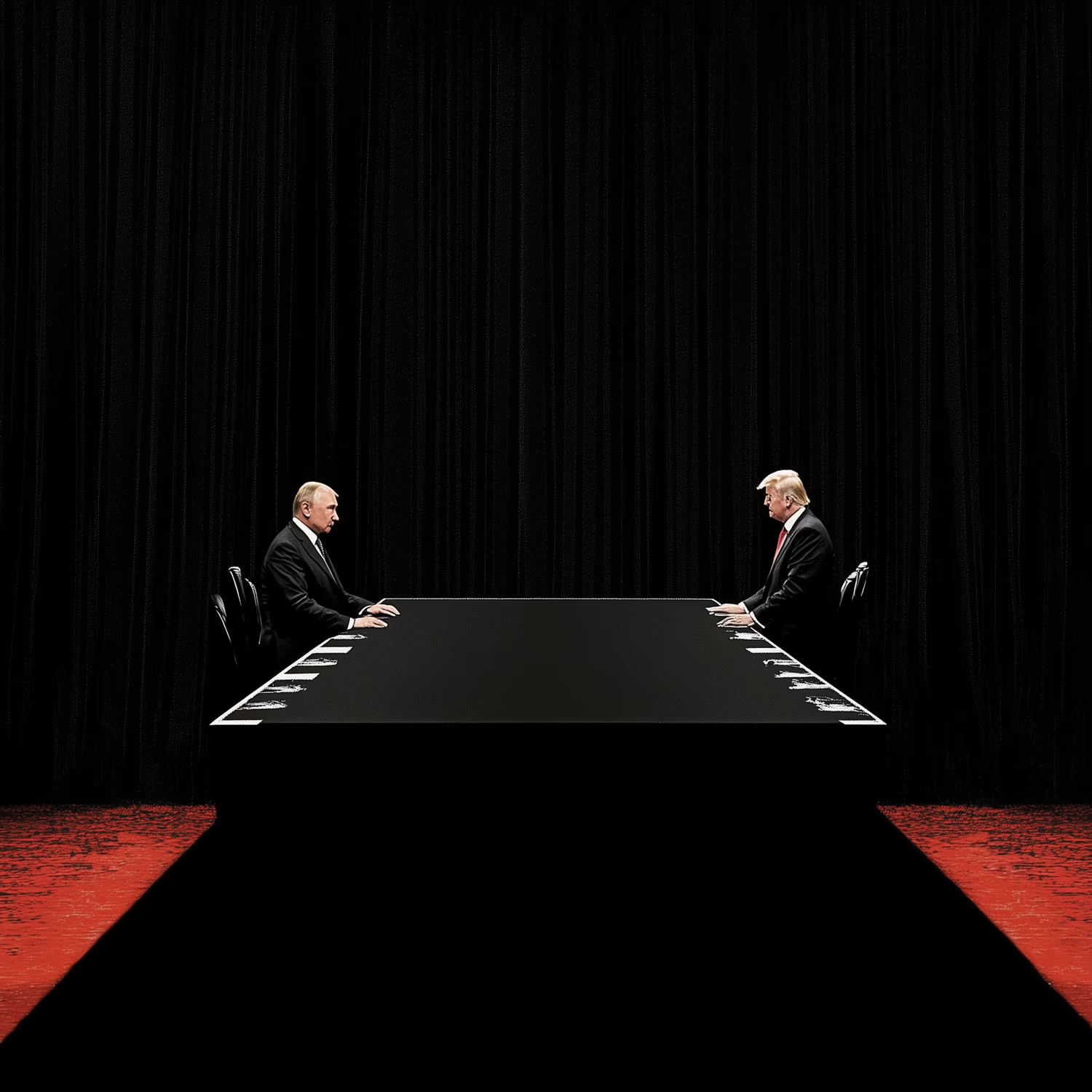

"This is Europe's worst nightmare," writes The Economist as it describes the new reality confronting the West. The illusion that the war would remain confined to Ukraine, that decisions could be endlessly delayed, that debates over arms supplies could drag on while bureaucracy operated at its usual pace—has crumbled.

For three years, Ukraine has fought Russia almost single-handedly. Western support has been measured and belated. It took Europe and the United States months to approve the transfer of long-range missiles, even longer to agree on training Ukrainian pilots. The promised million shells never materialized. While Ukrainian forces heroically held the front line, politicians in Brussels, Washington, and Berlin continued to deliberate whether their decisions might provoke Putin.

But that time is over. The war no longer feels distant. Moscow has strengthened military ties with Iran and North Korea, China is bolstering Russia’s defense industry, and Donald Trump is threatening to cut U.S. aid to Kyiv. Putin is no longer isolated, which means the strategy of containment at Ukraine’s expense is no longer sustainable. Europe now faces a choice: to persist in endless debates or to accept a reality where its own security depends on its resolve.

"Deep Concern," "Strong Condemnation," and "Call for Dialogue"

Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, European policy toward Russia has been dictated by fear—fear of provocation, escalation, and the possibility that the Kremlin might perceive support for Ukraine as a pretext for more aggressive actions. This fear shaped the rhetoric of European leaders, reducing their statements to hollow mantras: "deep concern," "strong condemnation," "call for dialogue."

But these declarations were never followed by measures capable of truly altering Moscow’s behavior. The sanctions imposed after Crimea were largely symbolic—designed to appear as a response while avoiding real damage to the Kremlin. Russian banks retained access to European financial instruments, energy giants continued selling oil and gas without disruption, and defense contracts between France, Germany, and Russia (including the notorious Mistral warships) were canceled hesitantly and with delays.

While Moscow waged war in eastern Ukraine through its proxies, Europe sought to "avoid provoking" Putin. Kyiv received neither lethal weapons nor significant military assistance. Even after the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 in 2014—when a Russian Buk missile killed 298 civilians—Brussels limited itself to condemnation and targeted sanctions that left Russia’s key economic sectors untouched.

Fear of Russia shaped European foreign policy not only toward Ukraine. For years, the Kremlin tested the limits of what was permissible—from cyberattacks on European institutions to the poisoning of political opponents on EU soil. The response was predictable: statements, meetings, "discussions on further steps." Yet no decisive actions were taken to force Putin into a choice—retreat or face real consequences.

This strategy of "not provoking" Moscow persisted for over a decade. But as history shows, appeasing an aggressor does not prevent war—it makes it inevitable. Europe ignored this lesson, choosing instead the illusion of stability.

Participant, But Not a Full-Fledged Ally

In 2007, Vladimir Putin addressed the Munich Security Conference, declaring that the West was pursuing policies that threatened Russia. This speech marked the beginning of a long confrontation in which Moscow sought to undermine Western institutions, while Europe and the United States maintained the illusion of strategic superiority.

The West responded with standard formulas: "We do not seek confrontation, but we will defend democratic values." In political terms, this meant that Europe had no real strategy to counter Russia. Years passed, the Kremlin wielded nuclear blackmail and wars in neighboring countries as instruments of pressure, while the West limited itself to condemnation and half-measures.

British political scientist Richard Sakwa argues that Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2022 was not inevitable—it could have been prevented, "if Western countries had developed a coherent policy that considered not only the threat from Moscow but also their own commitments to Kyiv." Instead, Ukraine found itself caught between two geopolitical blocs: too important to be simply handed over to Russia, but not significant enough to be turned into a full-fledged ally.

Ukraine was armed, but with constant caveats. It was promised support, but given no guarantees. It was used as a buffer, but never integrated into collective security structures. The West eagerly spoke of Ukraine as a stronghold of democracy, yet hesitated to make it part of its own defense architecture.

This is why the Cold War between the West and Russia escalated into a hot war between Ukraine and Russia. For Europe, it remained a geopolitical contest—a matter of sanctions, measured arms deliveries, but not a war requiring a radical reassessment of continental security. Kyiv paid the real price—in human lives, devastated cities, and millions of refugees—while Europe hesitated.

But now, that waiting game has ended. Putin is no longer isolated. Moscow has strengthened military ties with Iran and North Korea, Beijing is increasing its support for the Kremlin, and the United States teeters on the brink of political chaos that could wipe out its aid to Ukraine. Europe faces a choice: to continue behaving as if this war is someone else’s problem, or to finally acknowledge that the conflict can no longer be relegated to the periphery of its policy agenda.

The Cold War Is on the Verge of Turning Hot—For Europe Itself

Europe is unsettled. For the first time in decades, it is unsure whether the United States will come to its aid in the event of a real military confrontation with Russia. Donald Trump has made it clear that his America will no longer offer unconditional support to its allies. The future of NATO is now in question. European capitals anxiously parse statements from Washington, trying to decipher: if the crisis escalates into open confrontation with Russia, will Europe be left to face the threat alone?

This is an unfamiliar predicament for Europe. But Ukraine has lived in it for over a decade! Since 2014, it has existed in a state of uncertainty—relying on Western support but never fully assured of it. As The Economist writes, "last week was the darkest for Europe since the fall of the Iron Curtain." Ukraine is suffering from an acute shortage of weapons, Russia appears more menacing than ever, and America has suddenly ceased to be the continent’s security guarantor. Trump has not only sidelined European nations from negotiations over Ukraine—he is betting on reconciliation with Putin. But this nightmare extends beyond Ukraine. If the U.S. truly withdraws support for NATO, what will happen to Eastern Europe? How will Moscow act if it senses the Alliance’s weakness? How will Europe defend itself after decades of relying on American military power?

Not long ago, European leaders believed they were waging a Cold War against Russia with the backing of the United States. Now they realize they are in the same position Ukraine was in before 2014—alone in the face of a looming threat, hoping but uncertain whether help will arrive.

The difference is that Ukraine had no choice. Europe still does. But time for deliberation is running out.