On Friday evening, November 28, Andriy Yermak announced his resignation as head of the President’s Office amid mounting pressure over his possible role in a $100 million corruption scheme. For a man who spent nearly six years as Volodymyr Zelensky’s closest and most influential ally, this is more than a personnel reshuffle—it marks the collapse of an entire political construct.

A former producer and lawyer who became a key negotiator on war, security and relations with the West, Yermak built around the president a closed vertical that fused diplomacy, domestic politics and quiet operations against rivals. This text examines how the “Yermak vertical” was created, why it turned into a political liability for Zelensky, and what may happen to the system of governance after its architect steps aside.

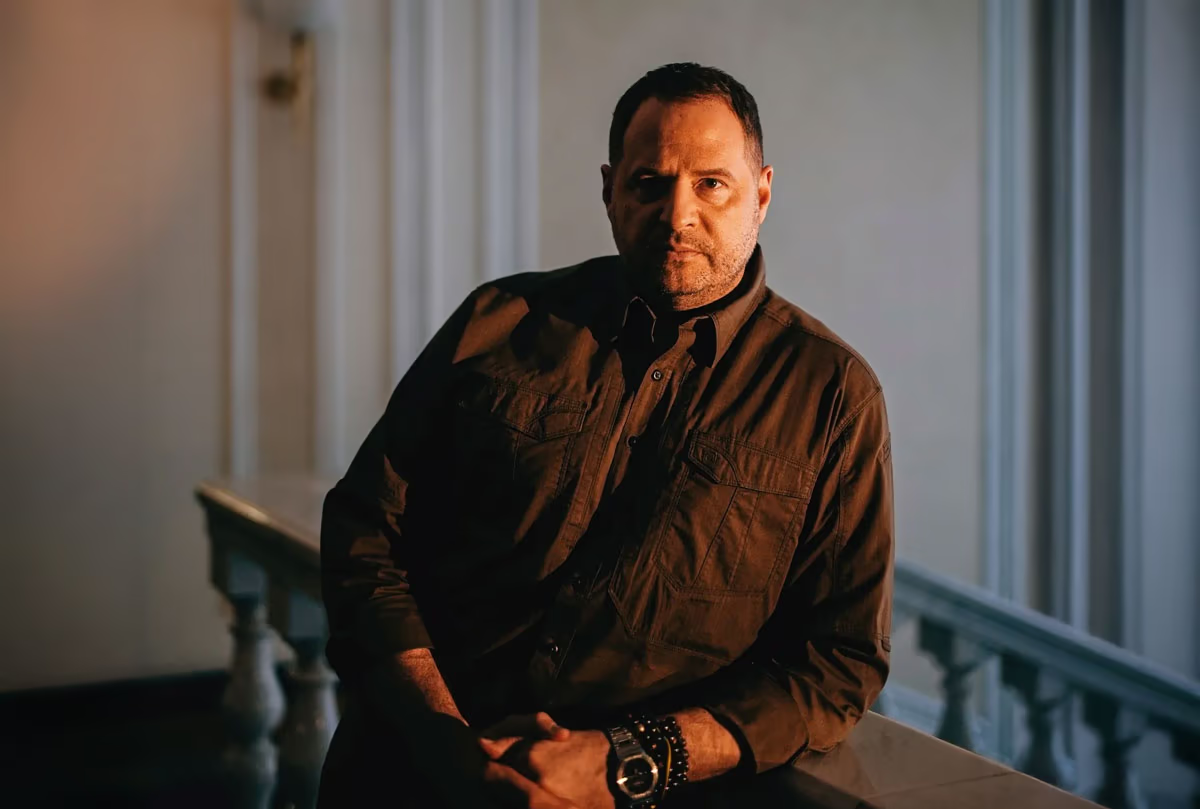

For years, Andriy Yermak remained in the president’s immediate orbit. At night, they slept only a few steps apart in the bunker beneath the administration building; at dawn, they exercised together. During the day, the 54-year-old chief of staff rarely left Zelensky’s side, appearing to his left or right in countless photographs from diplomatic meetings and official events.

That is now in the past. On Friday evening, November 28, Yermak submitted his resignation—or rather, was forced to do so—amid growing pressure over his possible link to a $100 million corruption scheme that has shaken Ukrainian politics. He was not listed as a suspect in the case involving the alleged misappropriation of funds intended for building air-defense systems and protecting Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. Yet opposition lawmakers claim his name appears in the investigative materials, and on Friday morning anti-corruption officials searched the office of the former film producer.

Zelensky Came to Power Promising to Eradicate Corruption

Now His Inner Circle Is at the Center of a Major Kickback Scheme in Energoatom

The Corruption Schemes That Never Stopped

How the “Mindich Tapes” Scandal Deepens Public Disillusionment in Wartime Ukraine

Is he guilty? Yermak denies any involvement. Yet for many of the president’s supporters, his departure came as a relief—a move that allowed Zelensky to distance himself from a figure without an electoral mandate who, through sheer proximity to the president, had amassed an exceptionally broad range of political powers. Critics described this “green cardinal” as, in effect, Zelensky’s bodyguard, personal fixer and, simultaneously, a substitute foreign, defense and interior minister.

Even long before the scandal emerged, Yermak enjoyed the trust of only 17.5 percent of Ukrainians, according to a Razumkov Center poll, while the president’s approval stood at 60 percent. Unlike most of Zelensky’s allies, he had not known him since school. Their paths crossed through the television world: Zelensky was its star, and Yermak a lawyer working in the industry.

From Zelensky’s personal manager to the system’s architect: how Yermak rewrote the balance of power around Bankova

Last year, Zelensky offered a concise description of their relationship. Speaking to Bloomberg, he said: “I respect him for the outcome; he does what I ask him to do.” In wartime, that set of tasks could be nearly boundless—from drafting peace proposals and maintaining informal diplomatic channels to orchestrating exchanges that helped bring back Ukrainian service members or abducted children.

According to a detailed Financial Times report, Yermak’s influence reached so far that he even intervened in the conduct of military operations. Early this year, protesters gathered outside the presidential administration chanting: “Fire Yermak.” Rumors circulated that he had been behind an aborted attempt to weaken the anti-corruption agencies, which had come uncomfortably close to Zelensky’s inner circle.

Whether true or not, by that point the once-all-powerful aide had accumulated a long list of political adversaries. They accused him of nurturing the presidential team’s inclination toward suspicion and authoritarian methods, orchestrating “covert operations” against those deemed enemies or simply ensuring their dismissal. It became a refrain in political circles: he knew everything happening in Ukraine. And so an inevitable question followed—how could he not have known about the large-scale embezzlement of public funds meant to keep people from freezing in winter or dying under drone strikes?

Zelensky Tries to Contain the NABU and SAP Scandal—But Public Trust in Ukraine Has Already Eroded

As Protests Enter Day Five, the Presidential Office Considers Sanctions Against the Owner of Ukrainska Pravda Over Corruption Reporting

A Power Struggle at the Expense of Defense

At a Critical Moment in the War, the State Is Focused on Reallocating Authority

Yaroslava Barbieri, a research fellow at the Chatham House think tank, stresses that the timing of Yermak’s departure is crucial. Last weekend, the head of the President’s Office traveled to Geneva for talks with the United States on the 28-point peace plan, which Kyiv viewed as effectively accommodating Moscow’s demands. The Trump administration had long centered its attention on Ukraine’s corruption problems. Advocates of this stance argued that such concerns should justify restricting the distribution of multibillion-dollar financial aid.

According to Barbieri, “the corruption scandal had become so toxic for Zelensky’s image that this political vulnerability was genuinely dangerous amid revived negotiations on terms favorable to Moscow.” In the end, she adds, the president’s “self-preservation instinct kicked in.” As she puts it, “his desire to appear as a leader who puts loyalty to national interests above personal loyalty to close associates prevailed.”

Although European partners likely nudged Zelensky toward parting ways with Yermak, tensions with the White House had surfaced long before. It was the head of the President’s Office who advised Zelensky to pursue a meeting with Trump in the Oval Office—a meeting that ultimately collapsed—and it was he who, according to the FT, suggested handing the U.S. president a set of photographs of emaciated prisoners, after which the encounter fully unraveled. Both Republicans and Democrats had grown weary of Yermak’s sharp, lecturing tone; one source described him as a “bipartisan irritant.”

Members of Trump’s team urged Zelensky to dismiss him after that White House meeting—partly because Yermak needed an English interpreter—but those recommendations went unheeded.