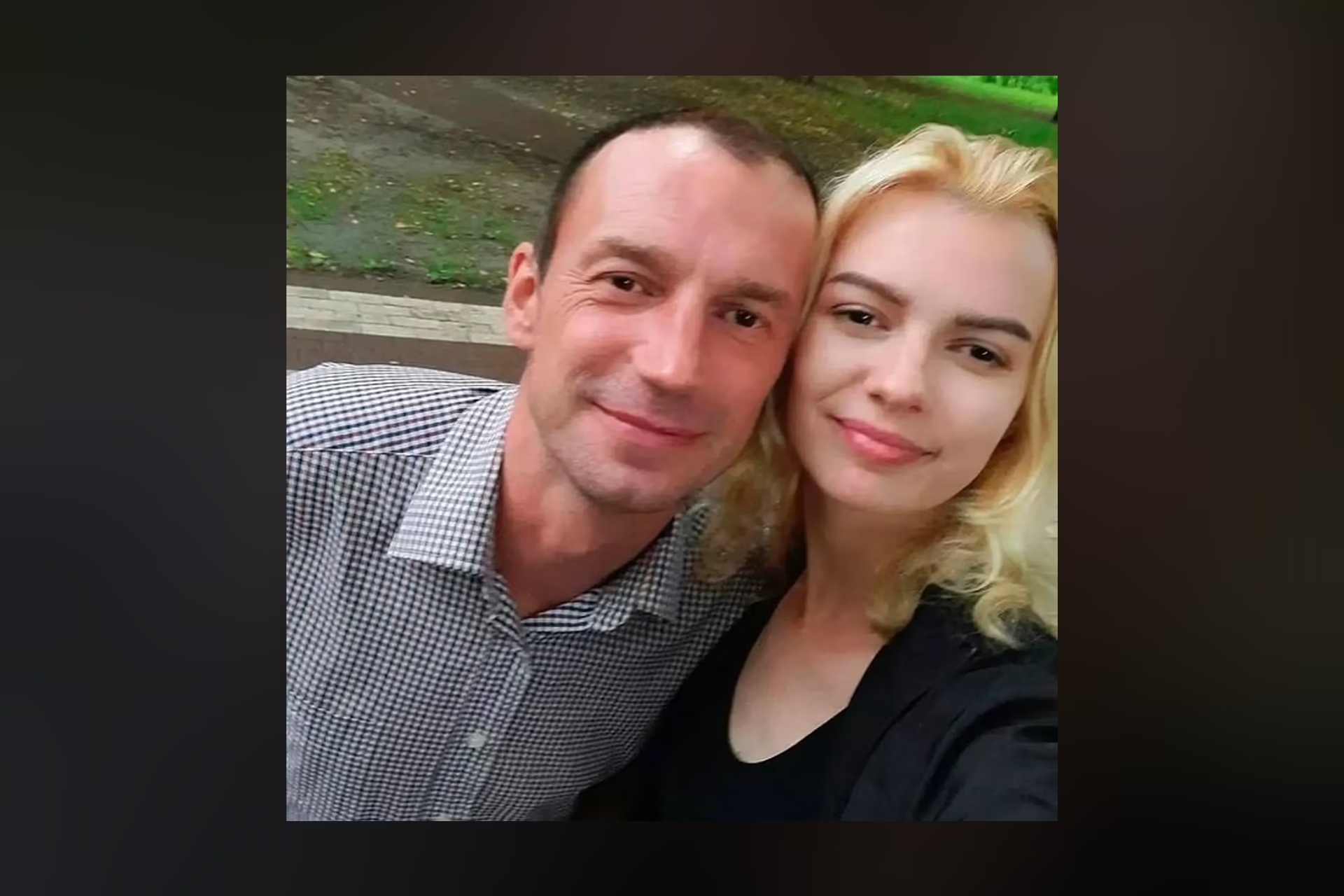

On August 22 in Charlotte, 23-year-old Ukrainian Iryna Zarutska was fatally stabbed aboard a light rail train; the release of surveillance footage sparked nationwide outrage. On September 9, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted Decarlos Brown under 18 U.S.C. §1992 (violence on mass transit resulting in death), a charge carrying a possible life sentence or the death penalty. Against this backdrop, President Donald Trump not only demanded capital punishment but also denounced the political and judicial system, writing on Truth Social: “the blood is on the hands of Democrats who refuse to lock up bad people.”

Decarlos Dejuan Brown Jr., 34, a resident of Charlotte, was homeless and unemployed at the time of the attack. According to his family, his mental health problems worsened after his release from prison in 2020: doctors had diagnosed him with schizophrenia and prescribed treatment, but Brown refused medication and displayed erratic behavior. His mother, Michelle Dewitt, sought involuntary hospitalization; after brief observation and release with prescriptions, he still abandoned treatment, became aggressive, spoke to himself, shouted unpredictably, and slammed doors. Fearing for their safety, relatives placed him in a homeless shelter shortly before the attack.

In January 2025, outside the Novant Health clinic, Brown repeatedly and without cause called 911, claiming in all seriousness that an “artificial material” had been implanted in his body that “controls when he eats, walks, and speaks.” After his arrest for Zarutska’s murder, he echoed similar statements in a jailhouse call to his sister, insisting he had never met or spoken to the victim before the attack and that “the material made me do [it].” Authorities have not established an official motive; police classify the assault as spontaneous, with no prior interaction between him and the passenger before the stabbing.

Criminal Record

Decarlos Brown’s criminal history stretches back at least to 2011, with no fewer than 14 arrests between 2011 and 2025. The offenses span a wide range — from simple assaults and disorderly conduct to theft and domestic violence. The key milestones in his record are as follows:

⋅ 2011–2013 — a series of arrests for minor offenses (assaults, public disturbances, theft); several failures to appear in court were recorded; he was placed on probation.

⋅ August 2014 — while on probation, Brown committed a major felony: armed robbery of a Honduran man, taking a phone and about $750. He was convicted of robbery with a dangerous weapon.

⋅ 2015–2020 — served a five-year prison sentence for armed robbery; released on parole in September 2020 under one year of supervision.

⋅ Late 2020–early 2021 — shortly after release, detained in connection with a domestic violence incident involving his sister. The family dispute apparently did not proceed to trial (see below).

⋅ September 2022 — arrested on suspicion of assaulting a woman and damaging property; final court records show no charges (the case was either not filed or dismissed).

⋅ April and May 2024 — twice detained for abusing the 911 system; both cases were closed and do not appear in court records.

⋅ January 2025 — third episode of improper 911 calls: Brown was detained outside Novant Health after repeatedly making baseless calls; the report noted his claims of “implanted artificial material” that “controlled his body.”

Brown accumulated at least 14 arrests, including incidents of violence, theft, disorderly conduct, 911 abuse, and armed robbery. In recent years, however, many cases did not result in long-term detention: charges were not filed, were dismissed, or did not lead to prison time.

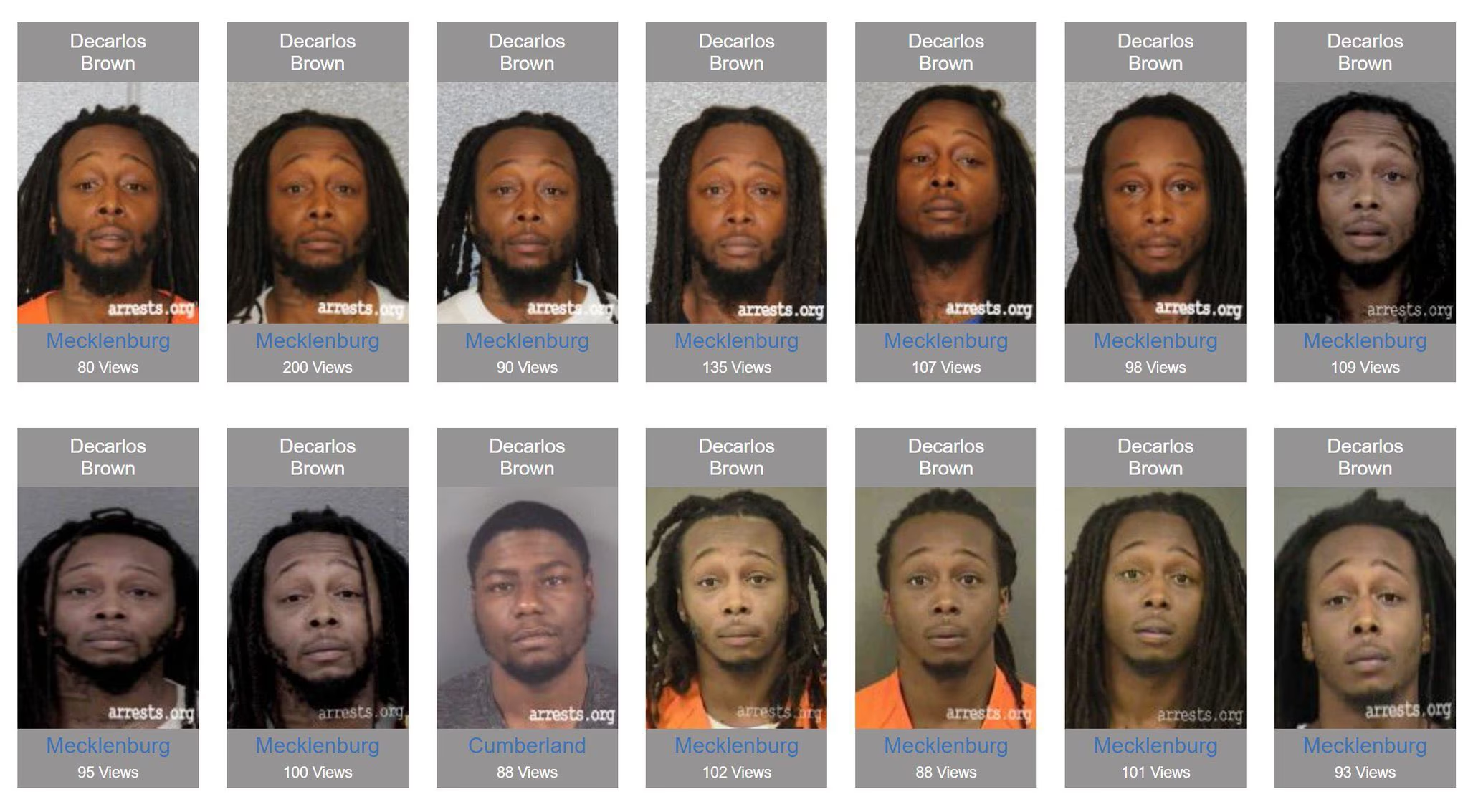

Mugshots of Decarlos Brown taken during various arrests over the years.

Why He Was Free

After serving his five-year sentence for armed robbery, Brown was released on schedule in 2020. Subsequent incidents were generally classified as less serious: judges often released him pending hearings, sometimes without bail, on a simple promise to appear. This was the case in January 2025, when after the 911 episode he was released without posting bail.

Given his behavior, the defense requested a competency evaluation. On July 28, 2025, the court ordered a psychiatric assessment, but it had not been carried out by the time of the killing. As a result, Brown remained free. After the murder, the court ordered a 60-day compulsory psychiatric evaluation in a state facility; his detention was set without bail. The Mecklenburg County District Attorney publicly admitted the case exposed vulnerabilities in how the justice and mental health systems handle repeat offenders with severe disorders, while the chief district judge launched a review of bail policies.

The Murder of Iryna Zarutska

Murder of Ukrainian Refugee in Charlotte Intensifies Dispute Over Democrats’ “Soft” Policies

Trump Accuses Them of Enabling Criminals, While Senator Tillis Had Already Opposed Federal Control of the City

Police Released Full Footage of Iryna Zarutska’s Killing in the U.S., With the Killer Facing Life Imprisonment or the Death Penalty

Ukraine’s Embassy and Major Ukrainian Media Have Not Mentioned the Incident Even Once

Ukraine Denied Irina Zarutska’s Father Permission to Travel to the US for Her Funeral

Her Relatives Publicly Criticize the Court’s Decision to Release the Repeat Offender and Point to the Inaction of Train Passengers During the Attack

The Life and Story of Iryna Zarutska

She Sought Protection in the US but Found Herself Most Defenseless There—While for Liberal Politicians and Media the Story Proved Inconvenient and Quickly Vanished From the Agenda in Both the US and Ukraine

Investigation Progress

Arrest and Police Statement. On the night of the crime, Charlotte police (CMPD) quickly detained Decarlos Brown at the East/West Blvd station. The police report confirmed his identity and age, noting that he had a minor hand injury at the time of arrest, was taken to a hospital, and then placed in custody. Police highlighted his “long criminal history dating back to 2011,” including theft, armed robbery, and threats. No motive was given; investigators described the attack as occurring “without any prior interaction” with the victim.

Charlotte Mayor Vi Lyles called the murder “senseless and tragic,” urged respect for the victim’s family’s privacy, and asked the public to allow investigators time. Members of the city council demanded stronger security measures on public transit.

On September 9, 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a federal charge against Decarlos Brown under the statute on violence against mass transportation resulting in death (18 U.S.C. §1992). Penalties under this provision include life imprisonment or the death penalty; capital punishment for first-degree murder is also provided under North Carolina state law.