In May 2024, the Ukrainian military publicly admitted for the first time that fortification lines in frontline regions were inadequately prepared for the new phase of the Russian offensive. The breakthrough in Kharkiv Oblast coincided with the release of a BIHUS Info investigation that exposed the financial underpinnings of the failure. The report revealed that tens of millions of hryvnias—out of some 40 billion allocated for the construction of defensive structures—ended up in entities with fake addresses, inflated budgets, and direct ties to regional officials and business figures connected to the presidential administration.

The investigation’s key finding: fortification works, officially outsourced to regional administrations, became a source of enrichment for a small group of contractors. These companies operated through shell entities, sold materials at markups of 30% to 300%, and were often linked to each other despite being registered under separate legal names.

Regional Administrations as Primary Stewards of the Defense Budget

Under Ukrainian law, the Ministry of Defense is not the main contracting authority for fortification projects. In 2024, the core budget—around 40 billion hryvnias (approximately $1 billion)—was redistributed through regional administrations. This arrangement not only accelerated the tendering process but also made it easier to divert funds with less risk of centralized oversight. The largest allocations went to the Sumy, Kharkiv, and Kherson regions.

How Contractors Resold Concrete Blocks to Themselves with Markups of up to 1,500%

In Kherson, the main contractor was a company called Global Build Engineering, which received over 200 million hryvnias to construct fortifications. According to BIHUS Info, the company had close ties to Anton Samoylenko, the deputy head of the Kherson regional administration. Global Build sourced nearly all materials through a single intermediary—Dnipropromsnaptorg—which was allegedly controlled by the same individuals. The markup between purchase and resale prices ranged from 30% to 1,500%, with total overpayments estimated at roughly 35 million hryvnias.

The Zhytomyr Scheme: Money Laundering via Shell Firms and Fabric Purchases

In the Zhytomyr region, a company called Navitekservice—previously involved in the “Big Construction” infrastructure program—was awarded a fortification contract but did not carry out any actual work. Instead, the funds were funneled to a firm named Reikvik, which had no staff, no registered capital, and no operational history. A portion of the money moved through a chain of obscure companies, while purchases amounting to tens of millions of hryvnias were recorded not as construction materials but as “fabric” (tkanina)—a classic scheme for cash withdrawals via fictitious procurement.

Links to Eventus, Mindich, and the Presidential Office — No Signatures, Just Adjacent Doors

BIHUS Info traced direct connections between key contractors in both cases and companies linked to Tymur Mindich—a business associate of President Volodymyr Zelensky and co-owner of the Kvartal 95 studio. The owner of Navitekservice is the brother of the head of Eventus Management, a company associated with Mindich. In Kyiv, the office addresses of firms receiving government contracts matched those of Eventus. These ties may not be formalized on paper—but they are consistent and persistent.

The Recurrence of Schemes Points to a Pattern, Not Chaos

If these were isolated incidents, they might be dismissed as inefficiency or negligence. But the similarities in structures, mechanisms, partners, and beneficiaries across different regions suggest something more systematic. Fortification contracts have become the latest revenue stream for the same networks that once profited from the “Big Construction” program—now repurposed for a more sensitive, but equally lucrative, sector.

No Consequences, Weak Oversight — and a Frontline That Pays in Blood, Not Money

Despite public investigations and clear signs of fraud, the contractors remain in business. Officials stay in office. And oversight mechanisms, if they exist at all, remain purely procedural. In wartime, this isn’t just a governance failure—it’s a threat. For every stolen hryvnia, the price is paid not by the budget, but by those on the front lines.

At Home

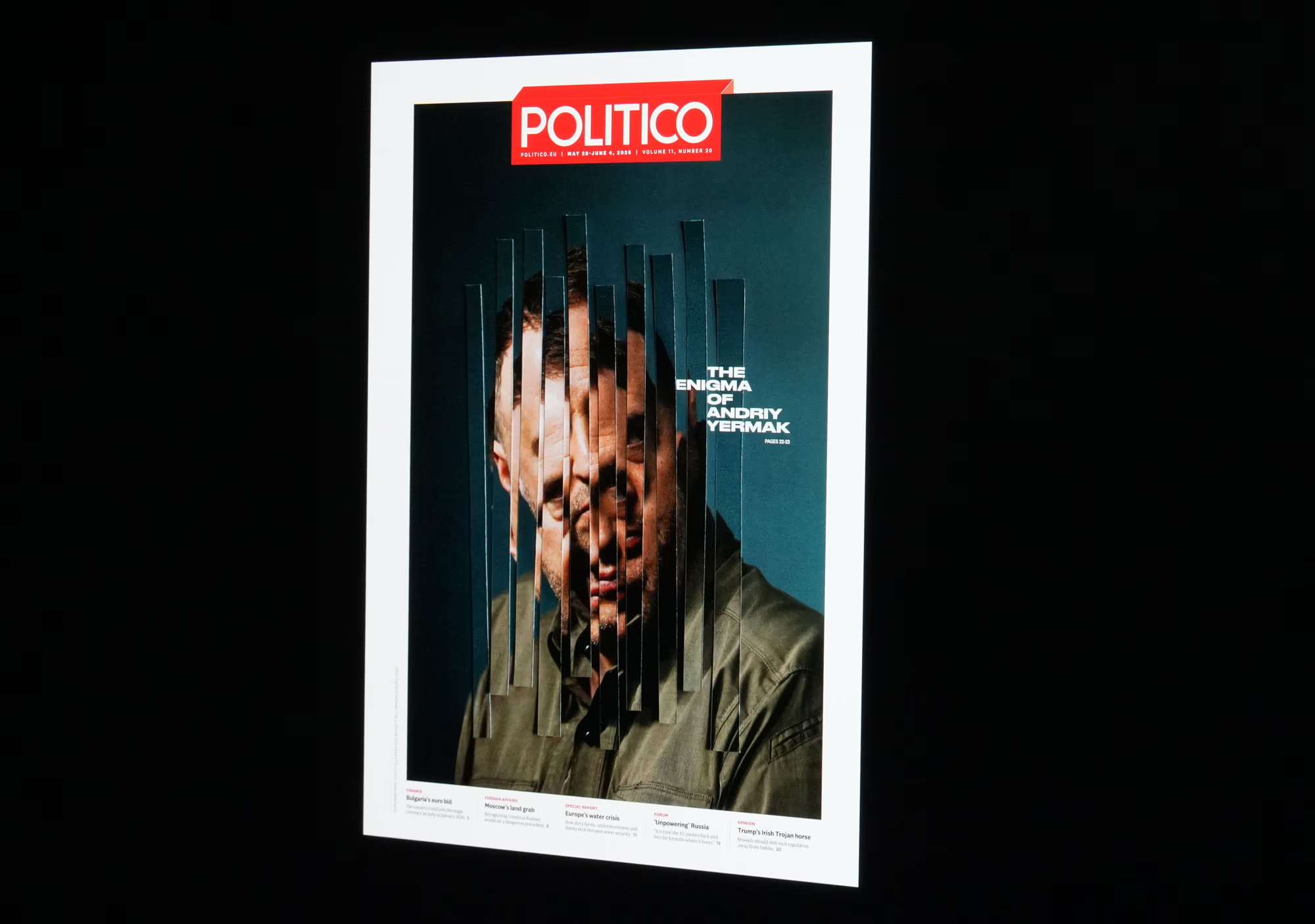

The Institution of Personal Loyalty

A Politico article explains how Andriy Yermak became Zelenskyy’s indispensable envoy—and the center of power in Ukrainian politics

Financial Times: Zelensky Accused of Targeting Anti-Corruption Activists and Independent Media

Raids, Cabinet Shake-Up, and Pressure on Oversight Bodies Fuel Concerns Over Democratic Backsliding

"By Removing Babel, You Remove the City’s Soul"

Odesa Becomes a Battleground of Cultural War, as Decolonization Starts to Mirror Soviet-Era Tactics

Ukraine's Disunity

Society must realize that only consolidation gives a chance for the future

Hundreds of Cases—and the First Call to Hold Someone Accountable

Kharkiv’s Mayor Condemns Draft Office Violence and Demands an Investigation