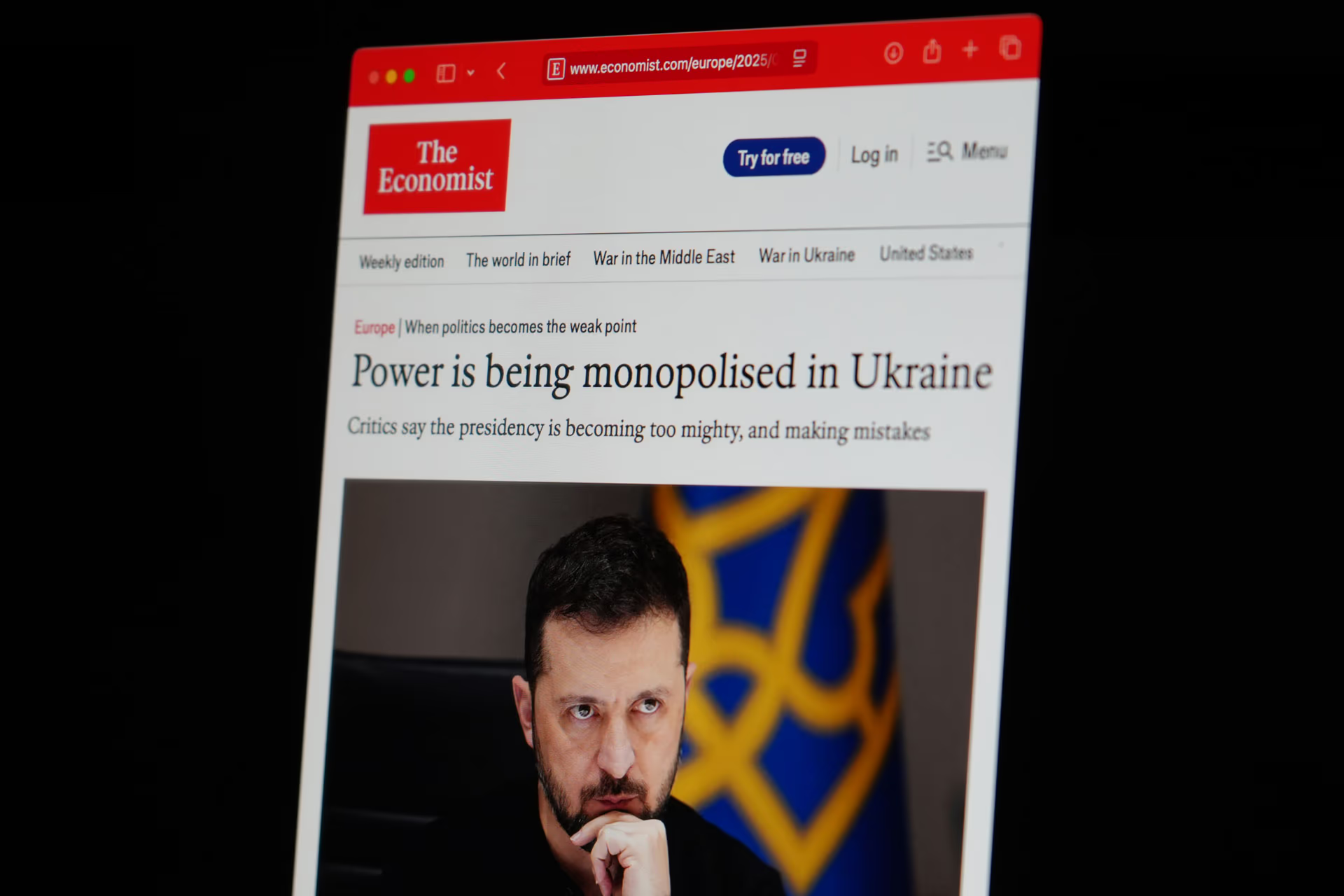

British magazine The Economist—one of the most consistent supporters of Ukraine in the international press—published an article titled "Power is being monopolised in Ukraine." Despite its restrained tone, the article may be the most direct and systematic critique of Ukraine’s leadership in recent months.

From the outset of the full-scale war, The Economist has been one of the most vocal supporters of Ukraine—diplomatically, economically, and militarily. That makes the magazine’s new article, focused on Ukraine’s internal governance problems, all the more striking—it reads like a warning.

The central point of the article: power in Ukraine is becoming concentrated in the hands of too small a circle—and this is starting to hinder the country, even during wartime.

The piece states that significant influence lies not with the parliament or the government, but with a handful of presidential appointees—including Andriy Yermak, Dmytro Lytvyn, and Oleh Tatarov. The administration is described as unwilling to share authority not only with opponents but even with potential rivals within its own ranks. Loyalists are appointed to state-owned companies, while those who show independence or enjoy broad support are removed.

Ukrainian reformers and civil society representatives, according to the magazine, are increasingly facing pressure. For example, anti-corruption activist Vitaliy Shabunin was sent to the front line, and his movements are reported to the authorities daily. He himself compares the tactics being used to the early years of Putin's rule—"at least in terms of petty vindictiveness."

The editorial notes that war naturally leads to a centralisation of power, but even Ukraine’s Western allies are beginning to express concern about how far it has gone. In the magazine’s view, Ukrainian democracy has never been rooted strictly in the rule of law—its resilience relied on competition between regional elites, a diversity of power groups, and an active civil society supported by Western embassies and the media. All of these checks have now been weakened.

"While the Western media and European leaders have lionised Zelensky and turned him into a celebrity, we feel trapped."

Yulia Mostovaya, editor-in-chief of the independent online outlet zn.ua

The Economist

Yulia Mostovaya, editor-in-chief of the independent online outlet zn.ua

The Economist

The article also highlights how the government’s attitude toward the opposition has shifted. In February, Petro Poroshenko was effectively sidelined from political life under the pretext of national security threats. His assets have been frozen, and he faces charges of treason. Many see this as a dangerous precedent. "If Poroshenko can be barred from an electoral process without any court decision, so can anyone else," says member of Ukraine’s parliament, the Rada, Oleksiy Honcharenko.

Against this backdrop, The Economist points to Ukraine’s impressive achievements in military technology. Independent teams of developers and engineers have established production of next-generation drones and missiles. One industry participant emphasizes: "We don’t want to have any dependence on America’s politics." However, the publication notes that growing state control may undermine the autonomy and innovation of these initiatives.

Despite all the challenges, Ukraine remains incomparably freer than Russia. But as Honcharenko stresses: "We have demonstrated that a small democracy can resist a larger autocracy and turn itself into a porcupine. But a small autocracy can be swallowed by a larger one."

What matters is not only what the article says, but who says it. If even The Economist—an outlet that has been an unshakable ally of Ukraine since the start of the war—is warning about the dangers of political concentration, this is not an attempt at destabilization but a signal. And it would be a mistake not to hear it.

At Home

The Institution of Personal Loyalty

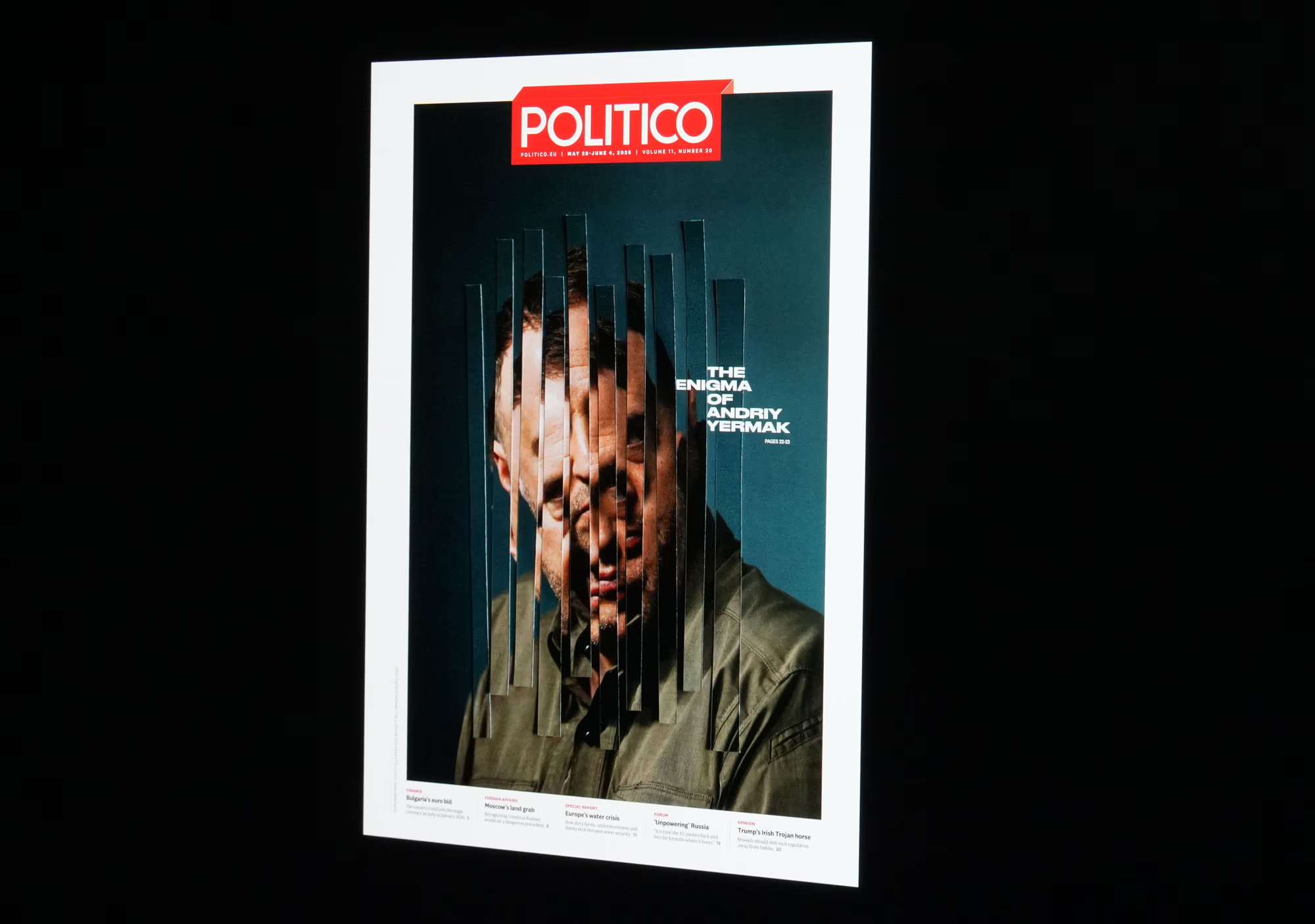

A Politico article explains how Andriy Yermak became Zelenskyy’s indispensable envoy—and the center of power in Ukrainian politics

Where Did the Billions for Fortifications Go?

BIHUS Info Exposes Price Inflation and Phantom Contracts in Ukraine’s Defense Construction Program

Council of Europe Report Documents Systemic Human Rights Violations Under Martial Law in Ukraine

Military Recruitment, Police, and Security Services Accused of Beatings—Some Fatal—Arbitrary Detentions, Persecution of Critics, and Conscription of People With Disabilities

"By Removing Babel, You Remove the City’s Soul"

Odesa Becomes a Battleground of Cultural War, as Decolonization Starts to Mirror Soviet-Era Tactics

Financial Times: Zelensky Accused of Targeting Anti-Corruption Activists and Independent Media

Raids, Cabinet Shake-Up, and Pressure on Oversight Bodies Fuel Concerns Over Democratic Backsliding