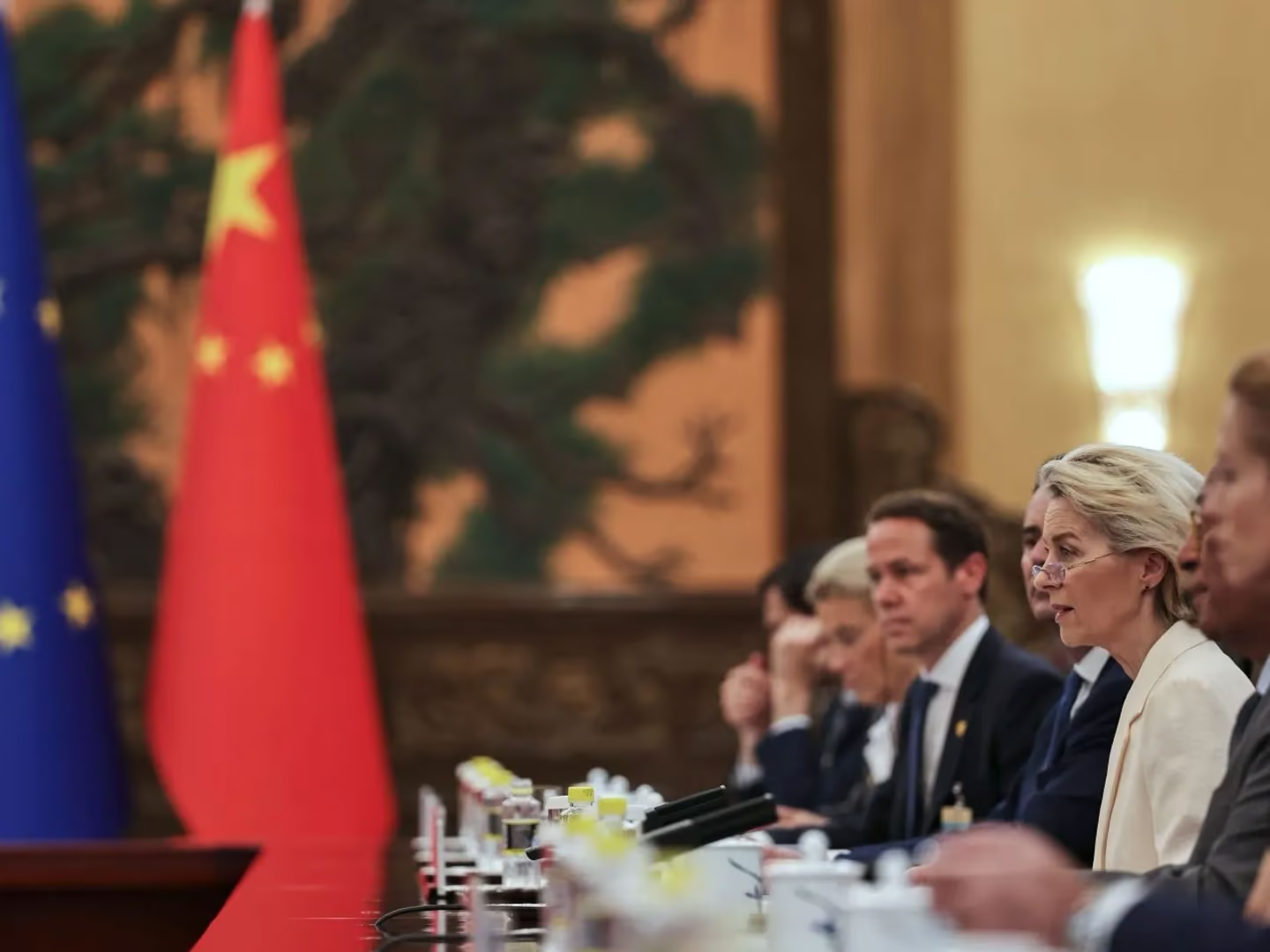

Last week's visit by European leaders to Beijing confirmed that the war in Ukraine remains a central factor shaping China’s foreign policy and its relations with the West. As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stated, the conflict is one reason why EU-China relations have reached "a tipping point." For Europe, China’s closeness to Russia and its perceived support for the war continue to be the main obstacle to restoring trust.

European Council President António Costa called on China in Beijing to "use its influence on Russia to uphold the UN Charter and end the aggressive war against Ukraine."

Beijing has tried to portray itself as a mediator in the search for lasting peace, but despite such statements, it has done little to bring the conflict closer to resolution. There is no domestic consensus in China—neither among experts nor the public—on the nature of the war, making it difficult to craft a unified foreign policy approach. Moreover, China’s strategic culture and close partnership with Moscow constrain its willingness to pressure the Kremlin into making concessions to Kyiv.

Still, the longer the war continues, the sharper the divisions between China and Europe become—and the harder they will be to bridge.

A Divided View Within China

Forty months into the war in Ukraine, China’s strategic community—from diplomats to commentators—still lacks a unified position. Heated debates between pro-Ukraine and pro-Russia voices continue even on Chinese social media.

Some experts and citizens view the war as Russian aggression against a sovereign state—an act that violates international law and principles China itself proclaims, such as the inviolability of borders and the rejection of force. This view also resonates with China’s historical memory as a country that endured foreign invasions. Ukraine also played an important role in China’s industrial development, particularly by supplying technologies and aircraft engines.

Yet another part of the elite views the conflict as an inevitable consequence of the Soviet Union’s collapse and the West’s attempt to assert control over the post-Soviet space. According to this logic, Russia is resisting NATO expansion just as Germany once rebelled against the conditions of the Treaty of Versailles. From this perspective, the war is part of a broader historical realignment rather than an isolated event.

Among the Chinese public, sympathy for Russia is fueled by a growing perception that China itself has become a target of containment policies pursued by the U.S. and Europe. Many see Beijing’s foreign policy as overly conciliatory, while Moscow projects a kind of "resolve" with which many Chinese citizens privately identify.

As a result, China’s stance on the war remains ambiguous. It’s not merely a balancing act between external interests and domestic views—many officials in Beijing genuinely recognize the validity of both narratives. This explains the 12-point position paper released by China’s Foreign Ministry in February 2023. It calls for "respecting sovereignty and territorial integrity," formally backing Ukraine, but also highlights "the legitimate security concerns of all countries," which is widely interpreted as an expression of empathy for Russia’s anxiety over NATO.

China has not recognized the annexation of Crimea, nor has it endorsed Russia’s claims to occupied Ukrainian regions. But it has also refrained from condemning them—because it does not want to take sides outright. This ambiguity is not merely a political tactic, but a reflection of a deeper internal split.

Made in China

The EU and China Agree on Climate—but Disagree on Everything Else

Environmental Cooperation Is an Exception Amid Trade Tensions and Political Distrust

How China Conquered the Rare Earth Metals Market and Took Control of Global Supply

What It Means for the U.S. and Europe Amid Rising Geopolitical Competition

Beijing’s Strategic Dilemma

China did not seek this war—and would likely have preferred it never began. Until February 2022, Beijing maintained friendly ties with both Moscow and Kyiv. Even after full-scale hostilities broke out, China did not sever trade with either side. While Western analysts often emphasize the deepening alignment between China and Russia, Ukraine remains a major trading partner for Beijing: in 2024, bilateral trade reached nearly $8 billion, despite the instability caused by the war.

Nevertheless, within Beijing’s hierarchy of foreign policy priorities, Russia holds a significantly more prominent place. It is a leading nuclear power and a neighbor with whom China shares a border of over 2,600 miles. Bilateral trade is approaching $250 billion annually. Moreover, Western rhetoric and actions in the context of the war have only drawn Moscow and Beijing closer: when Western leaders describe them as part of a single bloc—such as an "axis of autocracies"—it reinforces the Chinese leadership’s suspicion toward the U.S. and Europe.

The notion of a "no-limits partnership" between China and Russia, popular in Western commentary, often overstates the depth of their alignment. While the phrase is routinely used by Chinese officials, it remains largely symbolic—a gesture more than an accurate reflection of the bilateral relationship. As with any international partnership, ties between Beijing and Moscow involve disagreements, contradictions, and potential points of friction.

China’s strategic gravitation toward Russia often obscures the practical challenges of this partnership. Sanctions compliance in the financial sector has complicated transactions between Chinese and Russian firms. In 2024, growth in bilateral trade plateaued, and in the first half of 2025, trade volume declined by nearly 10%. Meanwhile, despite ongoing accusations that Chinese components are used in Russian weaponry, Ukraine itself actively deploys Chinese drones and uses Chinese parts in domestic drone production.

A Potential Mediator Without Leverage

In theory, China could play a meaningful role in brokering negotiations. In recent years, Beijing has grown more active in international mediation efforts—it was China that helped restore diplomatic ties between Iran and Saudi Arabia. If Beijing were to facilitate peace between Russia and Ukraine, it would not only remove a major obstacle to improving its relations with Europe, but also offer China a chance to shape a multipolar world order—countering the rigid narrative of "China and Russia versus the West." A successful resolution of the war under Chinese mediation would bolster Beijing’s image as a responsible global power.

In practice, China is unlikely to emerge as a key player in resolving the conflict. Its involvement—if any—is likely to be that of a secondary participant: invited to the table, but not shaping the agenda. This war remains a direct confrontation between Russia and Ukraine, with the U.S. and Europe playing indirect roles through military support. If Moscow and Kyiv are not prepared for a ceasefire and remain skeptical of potential postwar security guarantees, Beijing will not be able to function effectively as a mediator.

Moreover, China’s diplomatic flexibility is constrained by its own foreign policy alignment. Its close ties with Russia hinder it from adopting a more neutral position: Beijing is reluctant to pressure Moscow into making concessions. Such restraint is embedded in China’s diplomatic culture—when a country is viewed as an ally, Beijing refrains from criticism, even if it privately disagrees. Western states have repeatedly urged China to influence Iran, North Korea, Sudan, or Russia, but such calls have rarely yielded a response.

Tense relations with the U.S. and Europe further limit China’s role. Neither Ukraine nor its Western partners are likely to accept Beijing as the lead negotiator—fearing it would push for outcomes favorable to Moscow. Should other powers manage to halt the war, China might still seek to participate in peacekeeping or reconstruction efforts. But it is unlikely to spearhead the diplomatic path to negotiations.

The Central Obstacle

Despite Beijing’s stated desire to improve ties with European countries, the war in Ukraine remains the central source of friction between China and Europe. From the outset, Chinese analysts treated the conflict as important but distant—failing to anticipate its profound consequences for Europe or the extent to which it would complicate China-EU relations.

As early as 2019, the European Union officially labeled China a systemic rival, an economic competitor, and a partner. The first two designations proved easy to validate; the third—partnership—remains elusive. In Beijing, Western interpretations of Chinese policy are increasingly seen as corrosive to dialogue. As a result, Chinese leaders show little willingness to align with the U.S. and Europe on the war—particularly if it would require weakening ties with Russia. From Beijing’s perspective, it is Europe that must revise its misconceptions about China’s role in the conflict—not the other way around.

The outcome of the war—whenever it comes—will significantly impact the post-Soviet space and the future architecture of European security. If Russia emerges weakened, Eastern European and Caucasus countries are likely to deepen their alignment with the EU and Turkey, while Central Asian states will seek a more balanced posture—navigating between China, Russia, and other regional powers. Conversely, a resolution favorable to Moscow could reinforce Russia’s influence across these regions.

These potential scenarios are already shaping China’s strategic calculations. Beijing has a vested interest in a stable, open, and predictable environment along its borders to support trade and economic growth. Yet both possible outcomes of the war carry risks of renewed instability—including armed conflicts—that could strain China’s regional relations and present fresh challenges. Chinese analysts are increasingly debating what transformations the war’s end might trigger—and how best to prepare.

In trying to preserve neutrality in a war it neither initiated nor endorsed, China hoped to avoid escalation. But that approach has not delivered the intended result. On the contrary, contrary to Beijing’s expectations, the war has only solidified the confrontation among the world’s major powers—China, Russia, the U.S., and Europe. No party has benefited from this alignment—least of all Ukraine. And as long as the war continues, reversing this trajectory remains unlikely.