As early as 2021, U.S. and British intelligence agencies concluded that Russia was preparing for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Those assessments, however, failed to trigger a meaningful response—either from European partners or from Ukraine’s leadership, where the warnings were dismissed as exaggerated or unlikely. Guardian journalist Shaun Walker, drawing on more than a hundred interviews with intelligence officers, government officials, and diplomats from multiple countries, has meticulously reconstructed the sequence of events and the way in which key decisions were made. Below is a summary of the main findings of his investigation.

Looking back, Western analysts believe that Vladimir Putin made the final decision to invade as early as 2020. That year, Russia adopted constitutional amendments that allowed him to remain in power beyond 2024. It was also the moment when the country was engulfed by the pandemic and Putin retreated into isolation—sharply curtailing personal contact while, according to those who spoke with him, spending long hours reading books on Russian history and, it appears, reflecting on his own place within it.

The same year saw the violent suppression of mass protests against Alexander Lukashenko in Belarus, while in Russia Alexei Navalny was poisoned. Taken together, these seemingly disparate events reinforced Putin’s drive toward further consolidation of power and pushed him toward the pursuit of great-power ambitions.

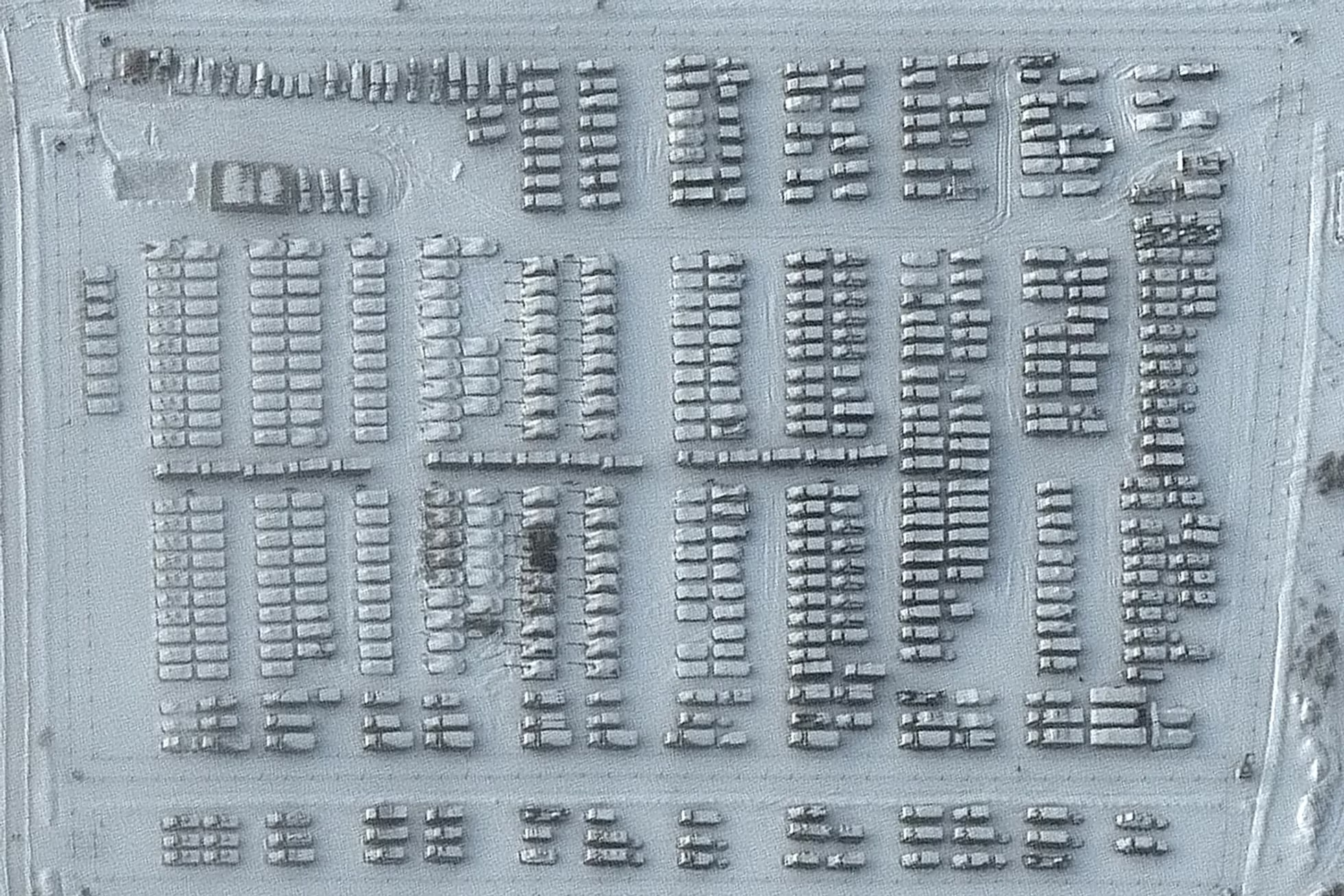

In the spring of 2021, Russia began massing troops along Ukraine’s borders and in Crimea, formally describing the buildup as military exercises. U.S. intelligence received information suggesting that in his address to the Federal Assembly on April 21, Putin might employ rhetoric designed to justify a military invasion. One scenario under consideration involved the formal annexation of the Donbas “people’s republics” and the creation of a land corridor to Crimea—which would have required Russia to seize parts of the Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions as well.

Joe Biden contacted Putin, expressed concern, and proposed a high-level summit. The exercises ended, Russian units pulled back from the border, and Putin’s address itself turned out to be unexpectedly restrained. In June, the presidents of the United States and Russia met in Geneva, where Ukraine was scarcely discussed. At the White House, the conclusion was drawn that the immediate threat had passed.

Yet in July, Putin published a lengthy essay titled “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.” It was widely interpreted as a signal of the Kremlin’s real intentions—including within Western intelligence services, where the text was read as confirmation that keeping Ukraine within Moscow’s sphere of influence was of fundamental importance to Putin.

In the autumn of 2021, against the backdrop of the Zapad military exercises, Russia once again began building up its forces along Ukraine’s borders and in Belarus. The United States obtained new intelligence pointing to a far more ambitious plan—not a limited operation, but an attempt to effectively seize Ukraine, storm Kyiv, and install a compliant regime. At that moment, the Biden administration’s attention was largely absorbed by the fallout from the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, which had dealt a serious blow to its international standing.

In November, Biden dispatched CIA Director William Burns to Moscow. His mission was to deliver a direct warning: Washington understood what was being prepared, and an invasion would bring catastrophic consequences for Russia. Putin, however, declined to receive Burns in Sochi—the conversation took place only by phone.

The warnings had no effect. Upon his return to Washington, Burns, at Biden’s request, offered his personal assessment and stated unequivocally that Putin intended to attack Ukraine.

Soon afterward, U.S. Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines traveled to Brussels, where she delivered a closed briefing to the heads of NATO intelligence services. She shared portions of the American intelligence and its central conclusion—Russia was preparing an invasion. That assessment was publicly endorsed by Richard Moore, the head of Britain’s foreign intelligence service, MI6.

Most European counterparts, however, reacted with caution. The United States and the United Kingdom declined to disclose their sources, fearing they could be compromised. There was also the lingering memory of 2003, when U.S. intelligence justified the invasion of Iraq by citing evidence that Saddam Hussein possessed weapons of mass destruction—claims that later proved unfounded.

Finally, many Europeans viewed Putin as a rational leader and found it difficult to believe he would risk a de facto rupture with the West over Ukraine. In France and Germany, the troop buildup was seen as a form of pressure and a negotiating tactic, rather than preparation for a real war.

In Kyiv, signals from Washington and London were interpreted in much the same way. Britain’s defense secretary, Ben Wallace, personally told Volodymyr Zelensky that there was no longer any doubt an invasion was being prepared—the only question was timing. Zelensky regarded that assessment as excessive.

In December 2021 and January 2022, U.S. and British intelligence obtained a far more detailed picture of the impending operation. The core evidence consisted of satellite imagery of Russian positions along Ukraine’s borders and intercepted communications—likely not only at the field level but also within the General Staff. Additional indirect confirmation, analysts believe, may have come from sources inside the Kremlin itself. Although the circle of those privy to Putin’s plans was extremely small, it was impossible to miss that the president was spending increasing amounts of time with the military.

Hostomel. March 10, 2022.

By January, U.S. and British intelligence services knew that the invasion was planned from multiple directions, including from the territory of Belarus. They were aware of preparations for an airborne assault on Hostomel airport, which was intended to serve as a foothold for a rapid seizure of Kyiv. They also possessed information about plans to deploy sabotage groups into the capital, tasked with the physical elimination of Zelensky in the first hours of the operation.

Burns arrived in Kyiv with the same purpose—to warn Volodymyr Zelenskyy once again—but his words failed to have a decisive impact this time as well. The Ukrainian president feared that orders to prepare for war could trigger panic at home and be interpreted in Moscow as a deliberate escalation.

By mid-February, the United States, the United Kingdom, and several other countries began evacuating their diplomatic missions from Kyiv. French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz traveled to Moscow, hoping to persuade Putin to abandon a military scenario. On February 12, Joe Biden held his final phone call with the Russian leader. In its aftermath, the American president concluded that the decision for war had already been made and that Putin had no interest in negotiations.

Unable to shift Zelenskyy’s position, the Biden administration—above all National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan—turned to direct contacts with Ukraine’s military leadership, including the Main Intelligence Directorate. There, the threat was taken far more seriously, but launching full-scale preparations without a political decision was impossible—such a decision could be made only by the president.

On February 21, a carefully choreographed meeting of Russia’s Security Council was held. Formally, the discussion focused on recognizing the “DNR” and “LNR,” but for many participants—including within Russia’s elite—it became clear that the issue at hand was a war against Ukraine. Almost no one dared to object.

The following day, Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council convened. Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Valerii Zaluzhnyi insisted on the introduction of martial law, but Zelenskyy limited the response to a state of emergency. He appears to have assumed that Russian forces would confine their actions to the Donbas. Even then, however, he was informed that several sabotage groups were operating in Kyiv, tasked with assassinating him.

On February 23, American, British, and Polish intelligence services confirmed that the order to launch the invasion had been given. Despite this, the head of Germany’s intelligence service, Bruno Kahl, arrived in Kyiv—his subsequent evacuation would prove exceptionally difficult.

On the night of February 24, Russia launched a full-scale invasion. The Verkhovna Rada convened in an emergency session and imposed martial law. Zelenskyy spent much of the day speaking with Western leaders, beginning with British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, with a single request—to contact Putin and try to stop the war.

The paradox was that U.S. and British intelligence services, having correctly assessed Moscow’s intentions, overestimated Russia’s military capabilities while simultaneously underestimating Ukraine’s capacity to resist. They assumed Kyiv would fall within days. Yet the Ukrainian army, even though caught unprepared in the first hours of the invasion, managed to disrupt the landing at Hostomel and hold the capital.

Shaun Walker sums it up this way: the central lesson of this story for the intelligence community is that no scenario should be dismissed simply because it appears irrational or impossible.