After the strikes on vessels carrying narcotics from Venezuela, calls are growing in the U.S. for military action and possible strikes on Venezuelan territory. Senator Lindsey Graham confirmed that the scenario is already being discussed within the administration. Donald Trump himself recently dismissed the idea of ground strikes. “No,” he told reporters curtly aboard Air Force One. Meanwhile, the Pentagon continues to expand its presence in the Caribbean, as the line between anti-narcotics operations and interference in Venezuela’s internal affairs grows increasingly blurred.

What began in early September as a series of U.S. airstrikes on boats in the Caribbean—allegedly carrying drugs from Venezuela—has evolved into a large-scale operation against Nicolás Maduro. Over two months, Donald Trump’s administration has deployed 10,000 troops to the region, positioned eight U.S. Navy surface ships and a submarine off the South American coast, relocated B-52 and B-1 bombers, and placed the aircraft carrier Gerald R. Ford under Southern Command. The Navy calls it “the most powerful and lethal combat platform in the world.”

These moves marked a sharp reversal in Washington’s policy. After the January inauguration, the White House was split between advocates of military intervention—led by Secretary of State Marco Rubio—and diplomats favoring negotiations, including special envoy Richard Grenell. For the first six months, the latter held sway: Grenell met with Maduro and negotiated the opening of Venezuela’s oil and mineral sectors to U.S. companies in exchange for reforms and the release of prisoners. But by July, Rubio had convinced Trump that removing Maduro was not a matter of democracy but of national security. He portrayed the Venezuelan leader as a drug lord tied to the Tren de Aragua gang and argued that Venezuela had become a “cartel state.”

Trump Declared That the U.S. Is at War With Drug Cartels

The Administration Justified Strikes on Boats in the Caribbean Sea That Killed 17 People

U.S. Declares a “War on Narco-Terrorists” and Prepares Covert Operations Against Venezuela

Trump Pivots Foreign Policy Toward Latin America, Blending Threats, Sanctions, and Promises to Allies

In July, Trump ordered the use of force against several groups, including Tren de Aragua and the Cartel de los Soles, and soon doubled the reward for Maduro’s capture—from $25 million to $50 million. He later admitted that he had authorized CIA operations in Venezuela. “Now we are definitely looking at the land, because we already control the sea,” he said. According to The New York Times, U.S. officials have privately acknowledged that the campaign’s ultimate goal is the overthrow of Maduro.

Covert Operations and Their Failures

By declaring its intentions publicly, the White House forfeited the main advantage of covert action—the ability to deny involvement and control the fallout. Washington now bears sole responsibility for the outcome and risks finding itself in a position where its actions are too visible to deny and too limited to succeed.

Even under conditions of secrecy, such missions rarely end in success. A 2018 study found that of 64 U.S. operations during the Cold War, only about 10% achieved their objectives when they involved backing opposition groups. Assassination attempts on foreign leaders routinely failed, while the few successful coups—such as in Iran (1953) or Guatemala (1954)—did not bring lasting stability. Venezuela’s military, carefully “immunized” by Maduro against rebellion, makes such an outcome nearly impossible.

The U.S. has tried before. In 2019, Washington recognized Juan Guaidó as Venezuela’s interim president, but the military remained loyal to Maduro. A year later came the botched “Operation Gideon”—a seaborne assault on Caracas by opposition fighters and American contractors.

Juan Guaidó.

Such failures only deepen conflicts, fueling anti-American sentiment and provoking further violence. The history of U.S. interventions—from Guatemala and the Dominican Republic to Brazil and Chile—shows that none has ever produced a lasting democracy. They typically ended in dictatorships, repression, and protracted wars. Maduro now actively exploits this legacy, portraying Washington’s pressure as a continuation of colonial policy.

Limits of Open Intervention

Among possible overt measures, the White House could try to intimidate Maduro with the threat of force. But such tactics have only ever worked against weak states—like Nicaragua in 1909. Attempts to pressure leaders such as Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi through threats proved ineffective.

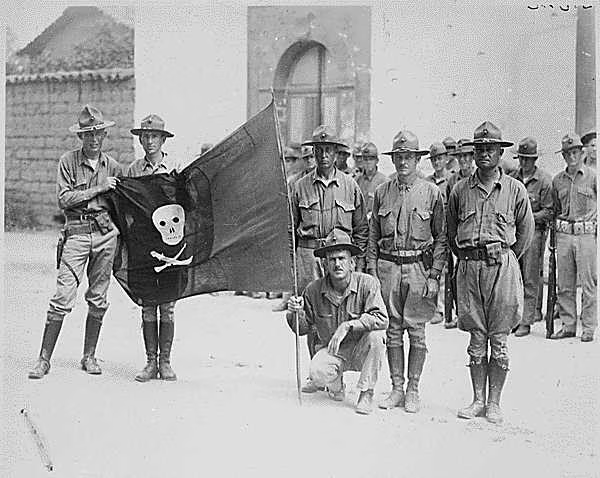

U.S. troops in Nicaragua pose with a captured Sandinista flag during the Banana Wars. 1909.

The prospect of relying on airstrikes also appears dubious. In theory, they could disrupt the chain of command and trigger a coup, but in practice no country has ever achieved regime change from the air alone. Modern communications make isolating leaders impossible, while bombing campaigns tend only to rally the army and population.

A ground invasion would require at least 50,000 troops—contradicting Trump’s promises not to entangle the U.S. in new wars. Even if he chose to proceed, maintaining control over Venezuela—a country twice the size of Iraq—would be nearly impossible. Comparisons with Panama or Grenada are misleading: Venezuela is a vast, mountainous state with jungles and porous borders, ideal terrain for guerrilla warfare.

After Regime Change—The Risk of Chaos

Even if the operation were to succeed, the aftermath would likely prove disastrous. The history of interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya shows that attempts to build democracy after the violent removal of a regime rarely end well.

Venezuela is a “kaleidoscope of armed groups”—from pro-government colectivos to Colombia’s FARC dissidents and the ELN. According to International Crisis Group expert Phil Hansen, the country “is literally saturated with armed factions of every kind, and none of them intends to disarm.” In such conditions, the risk of civil war is enormous.

Even a new leader installed with outside support would risk being seen as a puppet. Nearly half of such rulers are later overthrown by force. Venezuela, moreover, has a strong opposition led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate María Corina Machado. In the 2024 election, opposition candidate Edmundo González won more than twice as many votes as Maduro, but the results were annulled.

Proponents of intervention argue that U.S. military support could help establish democracy. Yet even polls favorable to Machado show that roughly a third of the population still backs Maduro—including much of the security apparatus. A 2023 RAND study warned that a military campaign in Venezuela would be protracted and extremely difficult to exit.

History teaches that foreign interventions are often built on distorted intelligence and inflated expectations. Napoleon III in Mexico and George W. Bush in Iraq both believed exiles who promised easy victories—and both became mired in wars. The Trump administration risks repeating their mistakes by failing to plan for what comes after regime change.

“America First”?

Regime-change policy in Venezuela runs counter to the principles Trump publicly espouses. He has repeatedly vowed to end the “forever wars,” claimed to have “stopped eight international conflicts in nine months,” and declared in Riyadh that nations should be free to shape their own destiny: “The so-called nation builders have destroyed far more countries than they have built.”

An attempt to oust Maduro would contradict that rhetoric, draw the U.S. into another conflict, strain relations with allies, and expand China’s influence in the region. A YouGov poll in September found that 62% of Americans oppose a military invasion of Venezuela, and 53% reject any use of force. Even in Florida—home to the largest Venezuelan diaspora—42% voiced opposition to intervention.

Moreover, such an operation would not bring the U.S. closer to its stated goals of combating drug trafficking and illegal migration. Venezuela does not appear in the DEA’s 2024 reports as a significant narcotics supplier, and the share of cocaine transiting its territory is below 8%. U.S. intelligence assessments deem it “highly unlikely” that Tren de Aragua coordinates major flows of smuggling or migration. Regime change would only intensify the refugee crisis.

Finally, intervention would undermine recent diplomatic gains. In the summer of 2024, Maduro offered to open all oil and gold-mining projects to American companies, redirect oil exports from China to the U.S., and limit contracts with Chinese and Russian firms—unprecedented concessions. Negotiations could have continued, but the White House chose a military path. If the goal is to protect U.S. interests, it would be more rational to return to diplomacy than to risk the chaos that a forced regime change would bring.