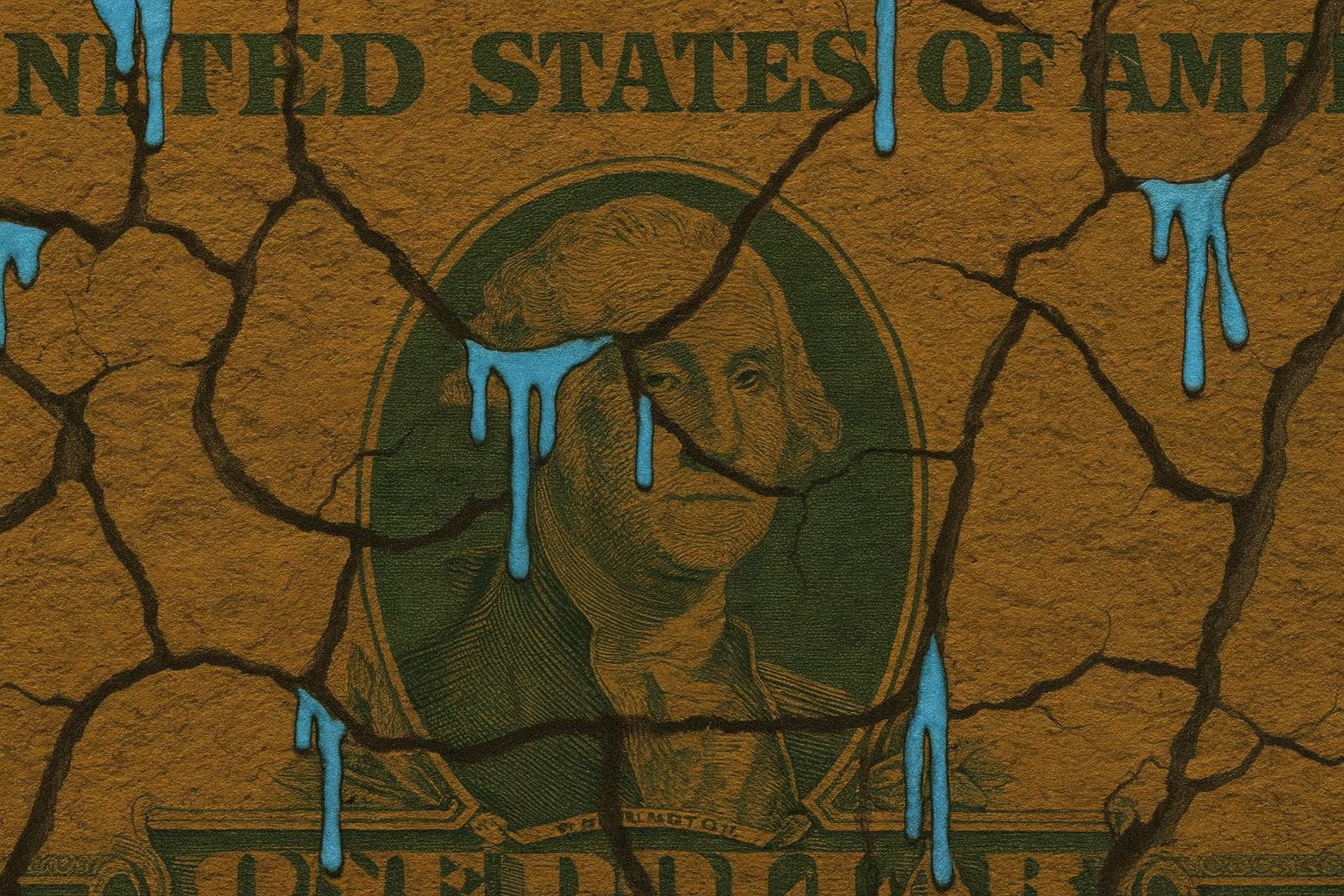

Donald Trump’s trade policy, built on aggressive tariffs, long served more as a political tool than a direct hit to Americans’ wallets. Businesses tried to cushion the impact: firms stockpiled goods, temporarily held prices steady, and hoped for tariffs to be lifted or eased. But since the new package took effect in July—15% on dozens of countries in addition to existing tariffs on China—room for maneuver has narrowed sharply. Rising cost pressures are now beginning to pass through to consumers, making higher prices inevitable.

U.S. companies are starting to pass on the consequences of Trump’s tariff policy to consumers. For months they held prices steady, hoping to ride out the uncertainty and absorb the blow with inventory. But after the new tariffs took effect in early July—roughly 15% on dozens of countries on top of the existing 30% on China—businesses have found their margins shrinking rapidly.

“Companies are reaching the point where their profitability is being squeezed, and they are forced to pass costs on to consumers,” said Cleveland Federal Reserve President Beth Hammack in an interview with CBS News.

The first signs are already visible. Home Depot had long kept prices in check by relying on inventory, but now warns of “modest movement in certain categories”—corporate language for price increases. Procter & Gamble has announced that about a quarter of its product range will become more expensive starting in August.

Tariff Policy of Trump

White House Tariff Policy Fuels Market Turmoil

Vague Statements, Last-Minute Adjustments, and Upcoming Court Rulings Undermine Investor Confidence

Who Invented Trump’s Tariff Policy That Shook Global Markets?

Meet Peter Navarro

The U.S. Economy as a Source of Global Instability

American Policymaking Increasingly Resembles That of Emerging Markets

The spotlight is on the auto industry. While manufacturers absorbed the costs, prices for new cars remained stable. But calculations by former GM executive Warren Brown show that this year alone tariffs will cost automakers $2,200 per vehicle. “GM, Ford, Stellantis, Toyota—they cannot absorb $2,200 per car. It’s impossible,” he told. According to him, within a month or two carmakers will quietly start raising sticker prices on 2026 models.

Official statistics still show only moderate inflation, but other data point to acceleration. Wholesale prices in July rose at their fastest pace in three years. A Harvard Business School tracker records rising prices among major retailers. Goldman Sachs estimates that by June companies were covering more than half of tariff-related costs, with consumers bearing just 22%. But if the trend continues, their share will rise to 67%.

The administration, by contrast, argues that businesses should continue to absorb the shock. “During COVID corporate profits were excessively high, and now we are returning to normal,” said Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent. In May, Trump even publicly urged Walmart and automakers to “eat the tariffs” and avoid raising prices.

For now, companies are trying to avoid a direct clash with the White House. But it is clear that sustaining the double pressure—from tariffs and a slowing labor market—will become increasingly difficult.