Two years ago, Ukraine was driven by different expectations. President Volodymyr Zelensky spoke of an imminent counteroffensive, while his inner circle promised Ukrainians they would soon be "sipping coffee on the Yalta promenade." As a symbolic gesture, Ukrainian Railways began selling tickets to Donetsk and Simferopol—for those who hoped to be the first passengers on trains to liberated territories. Backed by Western equipment and newly formed brigades, the counteroffensive was seen as the inevitable turning point in the war.

Since then, the frontline has shifted. Russia has expanded the area under occupation, intensified its attacks on Ukrainian cities, and moved dangerously close to the borders of Dnipropetrovsk region. And in Kyiv, despite the external threat, the internal struggle—for influence, resources, and control—is only intensifying.

Meanwhile, the front in Donbas holds thanks only to the limits of human endurance—exhausted but unbroken, Ukrainian soldiers maintain their positions under constant shelling.

One of the hardest-hit sectors is Kostiantynivka. Russian forces are concentrating here, attempting to replicate the encirclement tactics used in Avdiivka. Under drone strikes and near-total isolation, Ukrainian troops are fighting not just for ground—but for survival. One of them, Oleh Chausov, was badly wounded at the edge of a forest, waiting for rescue that seemed all but impossible.

Night Evacuation

In the dead of night, Ukrainian infantryman Oleh Chausov lay on the edge of a forest, writhing in pain—his leg, shoulder, and lung had been wounded. Then came bad news over the radio: evacuation was impossible. The road to positions in Kostiantynivka was under direct fire, with Russian drones circling overhead. "There were just too many of them," he recalls.

He was promised a remote-controlled tracked platform—a compact rescue robot, less visible to drones than an armored vehicle. It was operated from several kilometers away. When the machine reached him, Chausov dragged himself onto it with great effort. But 20 minutes later, there was an explosion—the platform had hit a mine. He survived and crawled to a trench, where he found shelter.

Meanwhile, the situation on the front was rapidly deteriorating. Russian forces had advanced 16 kilometers, forming a partial encirclement of Ukrainian positions around Kostiantynivka. From the east, south, and west—a tightening ring. Ukrainian soldiers report that any movement within this pocket is immediately spotted by drones, and the attacks are relentless, day and night. Troops remain in position for weeks without rotation and with no way to evacuate the wounded.

"Resupplying ammunition, rotating personnel—doing anything at all is extremely difficult," says Makas, an officer with the 12th Azov Brigade.

As a possible assault on Kostiantynivka looms, it remains unclear whether Moscow will opt for a frontal attack, as in Bakhmut, or attempt to close the ring and force a Ukrainian retreat—as it did in Avdiivka. Regardless of the strategy, Ukrainian troops point to Russia’s key advantage: air superiority and a sharp increase in drone usage.

"They used to strike from just two or three kilometers out," says Oleksandr, commander of a drone unit in the 93rd Brigade. "Now it’s every 10–20 minutes, at distances up to 15 kilometers. Anything within range is destroyed."

Endless, Still

Why Putin Keeps the War Going

The Kremlin Still Believes That Manpower, Missiles, and a War of Attrition Will Break Ukraine and Exhaust the West

Why Trump’s Peace Plan Is Stalling

Hard Lessons From the 2022 Talks

A Shift in Tactics

When Ukrainian troops talk about a turning point in Russia’s drone campaign, they most often mention "Rubicon"—an elite unit that first gained notice in Russia’s Kursk region, where it used attack drones to destroy Ukrainian supply lines. This spring, the same unit was redeployed to Kostiantynivka, where it quickly repeated the same tactics: targeting roads, vehicles, and communications.

"Everything changed when they showed up here," says Rebecca Matsiurovsky, an American volunteer and head of medical services for a battalion in the 53rd Brigade.

From a field hospital in Kramatorsk, 25 kilometers from the front line, she packs small batches of antibiotics, which are dropped by drone onto forward positions. It’s the only way to reach the wounded who cannot be evacuated. She always packs more than needed: "Sometimes the drone crashes. Then I put together another pack. And another. Until at least one makes it through."

Rebekah Maciorowski.

Relentless attacks have forced Ukrainian soldiers to spend nearly all their time in shelters. "Just getting to the toilet is almost a heroic act," says Mykola, stationed southeast of the city.

Last month, the head of the Donetsk regional administration urged civilians to leave Kostiantynivka, calling it "a matter of survival." But Russian control of the skies makes evacuation difficult. Thousands still remain in the city, which had a pre-war population of about 70,000.

Unpeace

Instead of Peace

JPMorgan Assesses Likely Outcomes of the War in Ukraine and the New Balance of Power in Europe

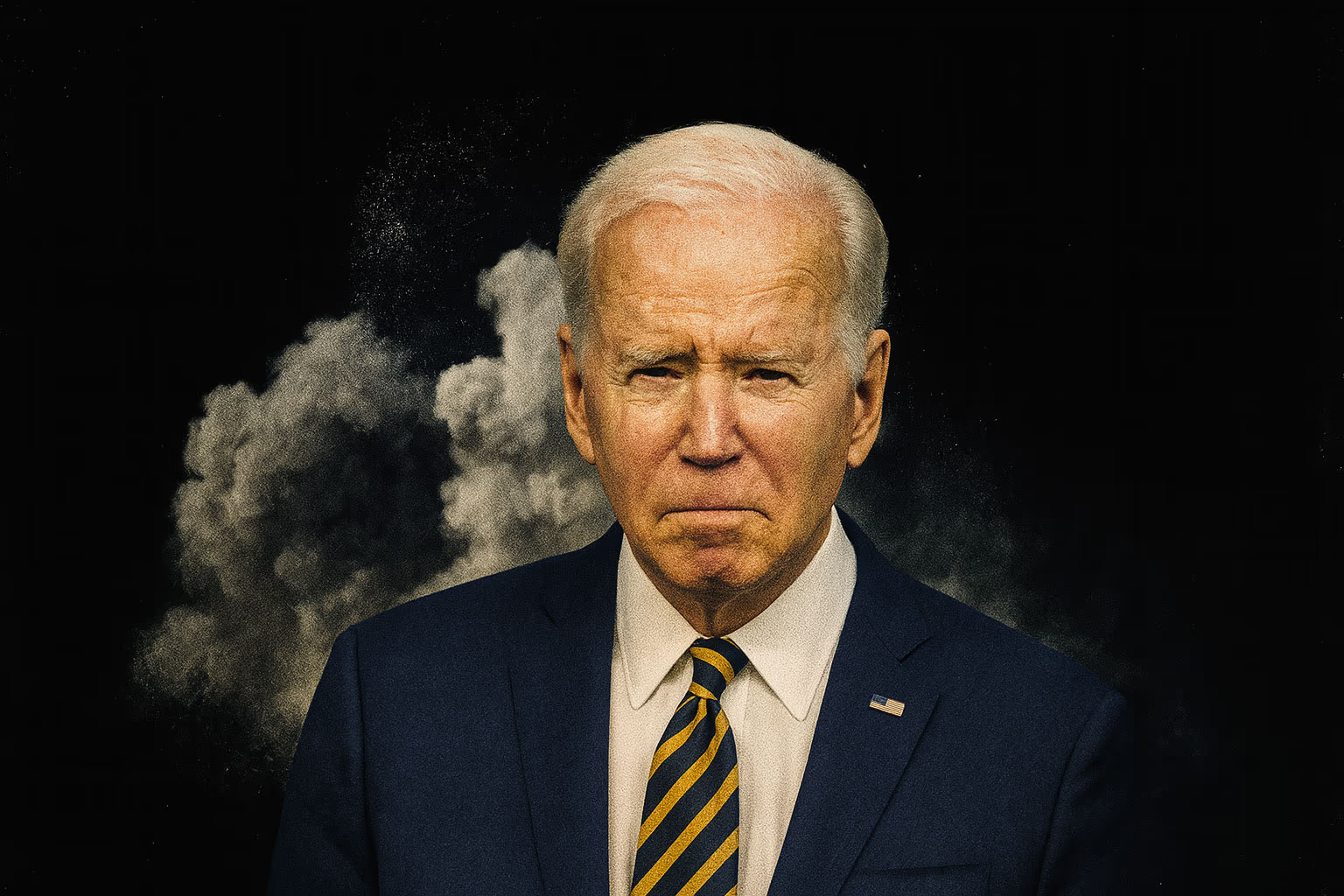

After Yet Another Failed Call With Putin, Trump Again Called the War in Ukraine "Biden’s War"

The U.S. President Has Repeated the Phrase So Often That We Decided to Examine What It’s Based On—and What It Leaves Out

At the Limit

Yevhen Tkachov, a volunteer with the humanitarian mission "Proliska," used to drive his pickup truck within 8 kilometers of the front line. Now, after drones targeted his vehicle, he stays no closer than 16. The pickup has been replaced with a modest car—less visible from the air.

The road into Kostiantynivka is scarred by impact craters: charred vehicles, shattered houses. In one stretch, a net has been strung up to intercept drones. The northern entrance to the city bears a banner: "Welcome to Hell."

On a recent Friday, Tkachov evacuated 74-year-old Tetyana Chubyna. She was trembling as she stepped out of the car. She hadn’t left her apartment for nearly a year—and only on the day of her departure did she see what had become of her city. "Everything is destroyed—the station, the homes, the factories. It’s horrifying," she said.

Russia continues to use heavy bombardment ahead of its advances. However, Azov officer Makas believes there won’t be urban combat in Kostiantynivka like there was in Bakhmut—instead, he expects Russia to try to encircle the city.

In these conditions, Ukraine is increasingly relying on drones and remotely operated machines—like the one that attempted to rescue Oleh Chausov.

According to Oleksandr of the 93rd Brigade, these platforms move slowly—about 20 km/h—which helps them stay less detectable. Each can carry up to 180 kg of supplies—food, water, ammunition. Most importantly, they allow for the evacuation of the wounded without endangering others.

"I’ve lost count of how many times soldiers have come under fire while pulling out a wounded comrade," says Matsiurovsky.

After the first machine hit a mine, Chausov was eventually rescued by a second one—it moved in under cover of night and reached the city by dawn. Medics pulled him out and brought him to the hospital.

He is now recovering in western Ukraine. "There were so many drones out there," he recalls. "It was a living nightmare."