Two years ago, The Economist outlined a vision of “Ukraine 2.0” — a project to be driven by reformers in power and an active civil society. The magazine admitted that the chances of regaining lost territories were slim, at least as long as Vladimir Putin remained in the Kremlin. But even if Ukraine managed to endure on reduced territory and become a safe, democratic, and prosperous country, that in itself would count as a victory.

Today, however, the picture looks bleaker on all these counts. Ukraine is surviving but gradually exhausting itself and losing room to maneuver. “We can keep fighting for years, slowly giving ground,” says one senior official. “But the question is, why?”

Let’s start with the situation on the ground. Considering how things could have unfolded, the outcome looks impressive. Three and a half years on, Russia has suffered military setbacks, though Ukraine too has endured heavy losses. Putin has failed to seize Kharkiv, just 35 kilometers from the border, let alone Kyiv. Flows of goods through Ukraine’s deep-water ports now exceed pre-war volumes. Russian warships have been forced to take shelter in distant Novorossiysk, pushed out of the Black Sea by Ukrainian naval drones.

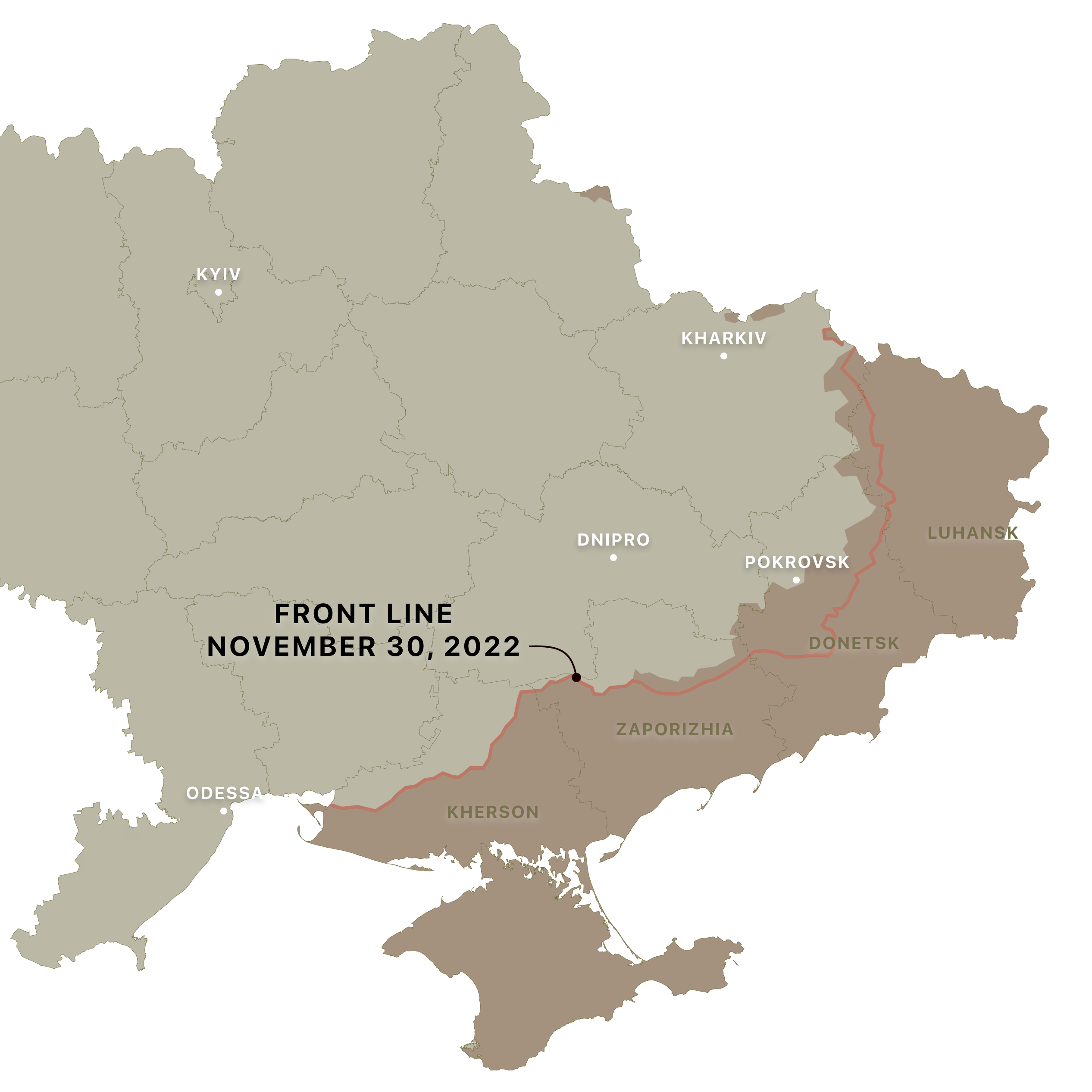

The front line has barely shifted since November 2022. Fighting for the small city of Pokrovsk in Donbas, once home to about 60,000 people, has dragged on for over a year. Russian losses are estimated at no fewer than one million killed and wounded. Meanwhile, Ukraine has turned the contact line into a drone battlefield: any movement within the 40-kilometer “grey zone” carries a deadly risk. Kyiv is capable of sustaining this mode of defense for a long time yet.

Occupied Territories of Ukraine on November 30, 2022, and September 24, 2025

Ukraine endures because its people have insisted on it. Much of the country’s security system emerged not thanks to the state but often in spite of its weakness. Parallel networks of civil society, business, and the military patched the gaps left by the Ministry of Defense, which officials themselves derisively call the “ministry of chaos.” Leading global drone manufacturers started out in garages and makeshift workshops. “When bureaucracy stalls, small groups create what the country needs,” explains an intelligence officer.

The problem is that Russia quickly copies Ukraine’s innovations and scales up mass production faster than Kyiv can respond. Meanwhile, mobilization is becoming more difficult and more brutal. The infantry faces a critical shortage of manpower. At the start of the war, Ukrainians paid bribes to get to the front; now, says a former draft officer nicknamed Fantômas, “they simply run away. The system collapsed last year.”

The prospect of a Ukrainian victory looks tenuous without a large-scale mobilization, which will inevitably be politically painful. People will have to be drawn from civilian sectors—and the sons of politicians, who are often shielded, will have to be sent to serve. The best possible outcome may be a compromise imposed by Trump. One senior Ukrainian official insists that the outline of such a deal is already visible, but most military commanders are sceptical and preparing for a prolonged confrontation. Deputy foreign minister and a senior negotiator Serhiy Kyslytsia does not expect a diplomatic breakthrough: “If I said Russia sells shit, that would be an insult to fertiliser. They sell air.”

Protests Exposed a Crisis of Zelensky’s Authority

Ukraine is beginning to run short not only of manpower but also of democratic legitimacy. “The trust between the authorities and society has collapsed,” admits one senior official. The climax came in the summer, when the government tried to curtail the work of two independent anti-corruption agencies whose investigations had edged close to the country’s leadership. Under pressure from allies and public outrage, the government was forced to back down.

Protests at the presidential residence—the first anti-war demonstrations against Volodymyr Zelensky since the full-scale invasion—proved a turning point. “From that moment the country will live in a ‘before’ and ‘after’,” said another official. The crisis showed itself not only in the government but in the authorities’ response to the protests. People managed to halt the abuses. Their homemade placards gave the movement its name—the “cardboard revolution”—and accused the authorities of far broader sins. One placard read: “You are not a tsar.” Another: “If you stole less, I’d bury friends less often.”

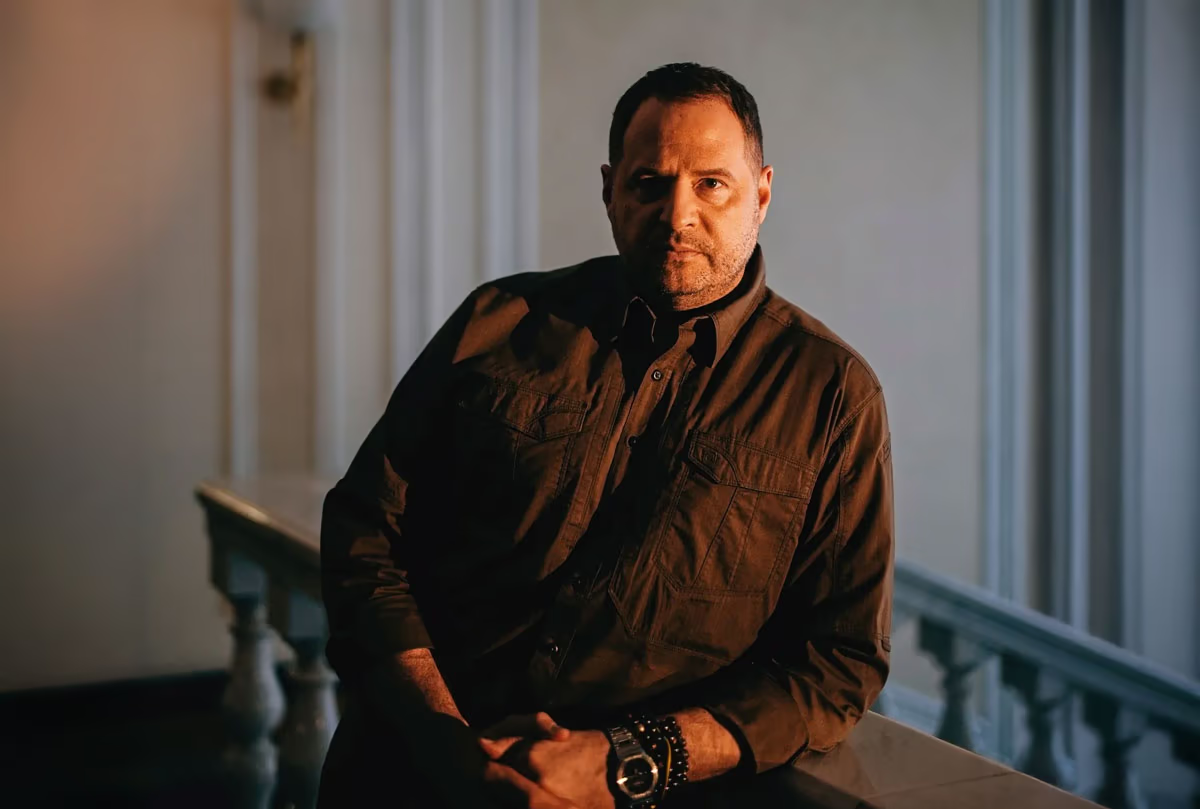

Zelensky, who won the 2019 election by a landslide and secured full control of parliament, has concentrated more power in his hands than any of his predecessors. The war and his decision to remain in Kyiv, inspiring the country to resist, further strengthened the vertical of power. Yet the heroic image bestowed on him by the West has bred arrogance. “Zelensky was more democratic at first, but the ovations carried him into orbit,” says one insider. “He began to believe in his own destiny.” Decisions are now made within a narrow circle of trusted figures, with Andriy Yermak, the head of the presidential office, at its centre. His influence, observers note, clearly exceeds both his experience and the status of an unelected official. One former minister calls Zelensky and Yermak “alter egos,” effectively running the country in tandem.

At Home

A Power Struggle at the Expense of Defense

At a Critical Moment in the War, the State Is Focused on Reallocating Authority

Financial Times: Zelensky Accused of Targeting Anti-Corruption Activists and Independent Media

Raids, Cabinet Shake-Up, and Pressure on Oversight Bodies Fuel Concerns Over Democratic Backsliding

The Institution of Personal Loyalty

A Politico article explains how Andriy Yermak became Zelenskyy’s indispensable envoy—and the center of power in Ukrainian politics

Meanwhile, the presidency itself increasingly mirrors Ukraine’s old vices. Threats against independent media and their advertisers, pressure on political opponents through lawsuits—including former president Petro Poroshenko—and extortion by the Security Service have become routine practices. A common tool of coercion is accusing targets of ties to Russia: one industrialist recounted how his colleague was forced to pay $2 million to avoid such an allegation.

There had been hopes that the July protests and the president’s subsequent reversal would halt this trajectory. But subsequent events suggest otherwise. On September 6, news broke of a brazen operation by Ukraine’s security services: the arrest in the UAE of fugitive ex-MP Fedor Khrystenko, accused of treason. The interest in him appeared less about the case itself than about an attempt to pressure him into testifying against an anti-corruption investigator probing the president’s circle. The season of scandals seems far from over.

Population Flight and Fiscal Gaps Erode the Economy

War has shaken Ukrainians’ faith in the future, and the impact is already visible in the economy. At a school in Kyiv’s central Pechersk district, the number of first graders has fallen by two-thirds. According to UN estimates, more than 5 million people have left the country. Most, sociologist Ella Libanova predicts, will not return. Business, already strained by missile strikes and power outages, is facing an acute labor shortage: many men are either at the front or evading mobilization, while women stay home to protect children during air raids.

Under such conditions, economic growth of 2–2.4% this year can be considered an achievement. Similar figures are expected next year, with or without a ceasefire. Economy Minister Oleksiy Sobolev notes that a third of this growth is driven by defense and technology companies.

EU membership remains an elusive goal—a kind of “Holy Grail” that could persuade citizens to accept painful reforms. “Many still naively believe they can become the Texas of the EU,” says Taras Kachka, the new deputy prime minister for European integration. But progress is uneven. Political obstacles stand in the way—from Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a Kremlin ally, to the interests of Polish farmers. Kachka is trying to accelerate the process, proposing to complete all necessary regulatory changes by 2030. “We have four years, and we cannot afford to lose a single day,” he emphasizes.

There are also more immediate problems. Russia’s invasion has blown a massive hole in Ukraine’s public finances. The country survives on external support, with all the distortions that entails. Taxes and domestic borrowing cover only basic military expenses—about two-thirds of the budget. Even the most optimistic forecasts project a $45 billion deficit next year, nearly a quarter of GDP. Western pledges amount to no more than $27.4 billion. “We have reached a point where there is simply no money,” laments one senior official. “And Europe itself has no funds that could bring us back to life.”

Ukraine Faces War or Elections

Ukraine faces two options—a fragile truce or a drawn-out war—and both look grim. “If the war ends, at least we will have a chance to climb out,” says one insider. But peace will bring its own tests: rebuilding a shattered economy, caring for traumatized soldiers, managing rising grievances, and sustaining a new army with less external aid. Continuing the war, while possible, will further drain the country. If fighting drags on and elections prove impossible, Volodymyr Zelensky will have to find new sources of legitimacy beyond his role as commander-in-chief.

It is clear that elections must be held as soon as security allows. The government appears to be preparing for a vote next year if negotiations succeed—approval ratings remain relatively strong. According to internal polling, Zelensky could win re-election: today he leads his likely challenger, former commander-in-chief Valeriy Zaluzhny, in the first round, though he could lose in a runoff. Yet many Ukrainians remain unconvinced of the merits of either candidate.

Despite the gravity of Ukraine’s predicament, hope should not be dismissed. Society has become far more engaged and now sets the tone in many spheres. The achievements of business, the ministries of economy and digital transformation, the army and defense industry command respect. But much of the central government is deteriorating. Zelensky appears to be running out of room for maneuver. Whether he can find a new path remains uncertain.