The digitalization of public services promises convenience and savings, but in practice it forces governments to choose: modernize their infrastructure at the risk of losing control over data, or preserve sovereignty at the cost of slower updates. London’s deal with Google and Brussels’ agreement with Microsoft revealed that the issue of storing and accessing information has become not only technical but geopolitical—and that citizens’ data are turning into a strategic asset, on par with energy or raw materials.

Society’s dependence on digital technologies deepens every day. The more domains move online, the more data we generate—medical records, financial transactions, consumer habits. The volume of information on the internet doubles roughly every three years.

Governments too are moving services online—from tax filings to medical files. In theory this should make processes faster and cheaper, but the reality is more complex. London’s new contract with Google made clear that even advanced economies face the same dilemma: modernization or control over their data. Under the terms of the deal, vast troves of information will be stored in the United States. Microsoft has already acknowledged that it cannot guarantee full autonomy to clients in France—or across the EU—if Washington demands access.

This raises a universal question: who owns our digital footprints, and can governments guarantee their protection? Since 2018 the EU has enforced GDPR, reinforced by the Data Sovereignty Act, the Data Act, and the NIS2 directive. These rules enshrine data sovereignty and restrict cross-border access, yet they cannot eliminate the risks altogether.

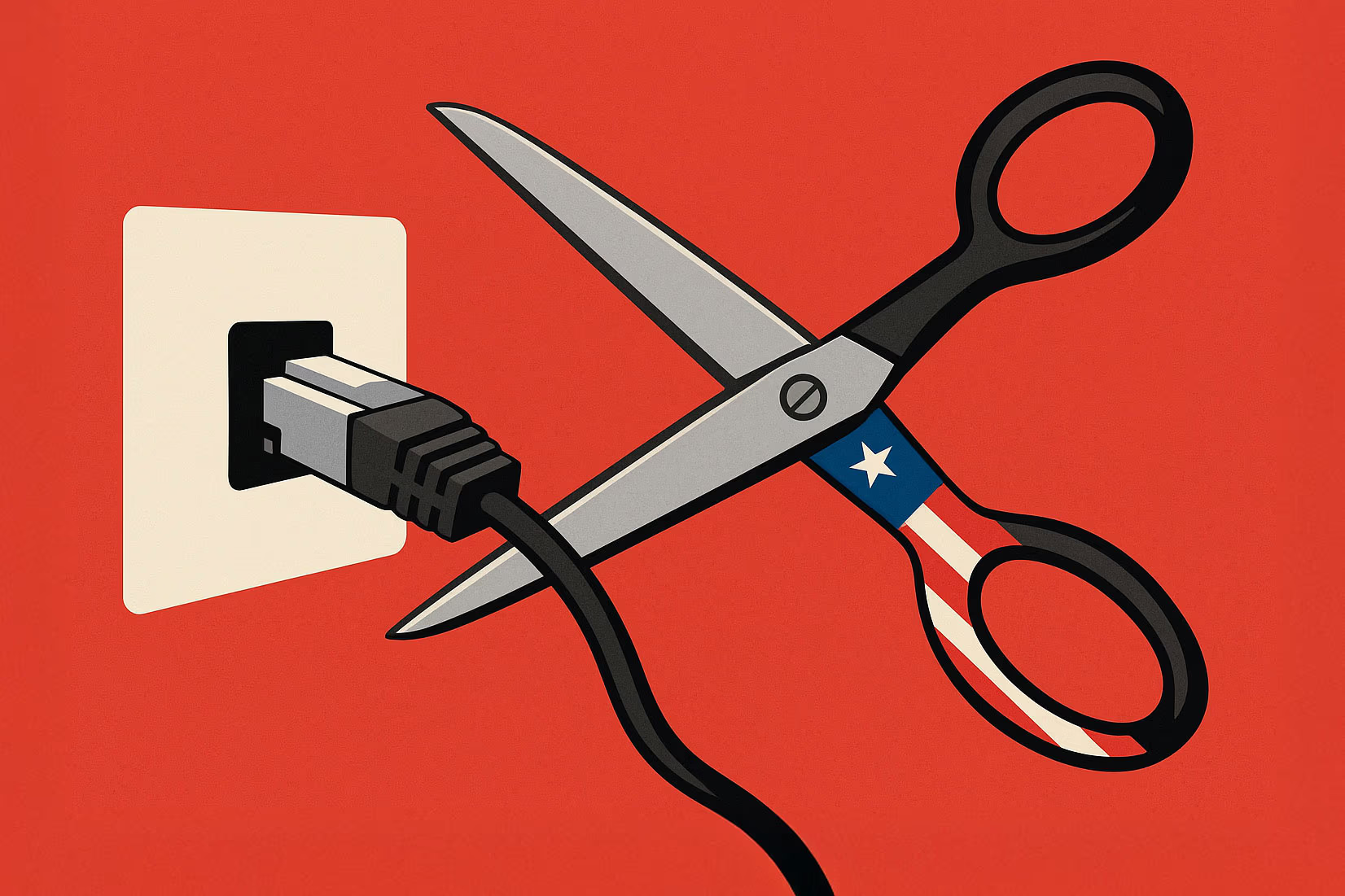

Digital Sovereignty, Outsourced

Politico: Europe Fears the U.S. Could Cut Off Its Internet

The Threat No Longer Feels Hypothetical

Hackers Attack Microsoft Servers Worldwide

Government and Energy Networks Breached in the U.S., Europe and China as U.S., Canada and Australia Launch Investigation

That is why Britain’s deal with Google has raised concerns. In July, the government announced that the company would modernize public infrastructure free of charge. More than a quarter of state systems—and up to 70% of those used by the NHS and the police—still rely on technology that is 30 to 40 years old. Google has pledged to replace them with cloud-based systems and invest hundreds of millions of pounds in "in-kind services". In return, the company secures access to future tenders and a reputational boost. But is it not naïve to hand over the management of state data to a multinational corporation?

The main risk is vendor lock-in: critical infrastructure concentrated in the hands of a single provider from another jurisdiction. Added to this is the reach of America’s CLOUD Act, which obliges U.S. companies to grant authorities access to data even when stored abroad. Officially, the law was designed to facilitate information-sharing, yet it clashes with Europe’s approach to privacy. Google insists that the technology will remain under London’s control and promises to challenge Washington’s demands. But is that enough?

The EU, meanwhile, is negotiating with Microsoft. The company has pledged to invest €5 billion in upgrading infrastructure, strengthening its hand in public tenders. Yet the risk of dependence is once again obvious. Antoine Carniaux, head of Microsoft France, has said bluntly that the corporation cannot guarantee data will remain out of reach of U.S. authorities. In response, the firm has floated the idea of diversified cloud centers in Europe. These include Blue—a joint venture with Capgemini and Orange in France—and a project in Germany with SAP and Arvato Systems. But the underlying problem remains: citizens’ data are a strategic resource, more valuable than gold.

International data-center governance bodies urge governments not only to defend national interests but also to build alliances that combine sovereignty with economic benefit. Still, outsourcing national computing capacity to foreign corporations cannot be a long-term strategy. Big Tech firms enjoy market capitalizations and budgets larger than those of many states, and their overriding priority is shareholder profit. Their financial muscle and lobbying power allow them to set the terms of engagement.

Google and Microsoft promise millions of pounds and euros in "free services" and an aura of goodwill. But their business depends on growth and profit. Any country with weak domestic capacities but the ability to pay regularly is an attractive client—especially if it has resources but lacks the technology to exploit them. Britain and EU member states fall squarely into this category. For the corporations, it is a fresh revenue stream and a way to sustain market capitalizations measured in trillions of dollars.

The enormous pressure on Big Tech to sustain growth should not become a government’s problem. Their priority must be national security, intellectual property, and the privacy of citizens. Hence the principle of data sovereignty: the state stores the information of its institutions, businesses, and population on its own systems. Today, this is part and parcel of national sovereignty.

A country’s physical borders also define the limits of its digital space. Unlike Coca-Cola or McDonald’s, Google and Microsoft derive their core profits from data itself. Little wonder that these corporations are eager to entrench themselves in the EU’s $25 trillion economy. Yet governments must place the inviolability of citizens’ data above all else.

Trustworthy alliances among states, safeguards for the integrity of national data, and caution in signing contracts are all essential. But data sovereignty demands constant vigilance.