The twelve-day war in June, when the United States joined Israel in striking Iran, marked the culmination of decades of confrontation, mistrust, and hostility. Since its founding in 1979, the Islamic Republic has pursued independence from the West and resistance to the United States, while Washington has responded with pressure: sanctions, regional military presence, support for allies, and interventions. The two sides have repeatedly come close to direct clashes: in 1987–1988 the U.S. destroyed Iranian oil platforms and ships and mistakenly shot down a passenger airliner; in 2020 the killing of Qassem Soleimani again brought the crisis to the brink. This year President Donald Trump crossed the line: the U.S. launched dozens of cruise missiles and 30,000-pound bombs against three Iranian nuclear sites.

For Iran’s leadership, the United States remains the principal external enemy—a source of threats and humiliation dating back to the 1953 coup and the subsequent shah’s dictatorship. The leaders of the 1979 revolution were convinced that U.S. policy drove Washington toward regime change and military intervention. In the 1990s Tehran already felt the pressure: the Gulf War, expanding American presence, sanctions. From the 2000s onward, sanctions and proxy rivalries were compounded by episodes of direct confrontation—from clashes at sea to strikes on Iran’s allies.

Many observers see in this history an unbroken line of confrontation. Yet escalation was not inevitable. Opportunities for rapprochement arose more than once—through mutual respect, the avoidance of ultimatums, and recognition of each other’s interests. Some were missed, others derailed by political circumstances, domestic struggles, and pressure from regional actors. Decisions in the White House, the absence of long-term guarantees, and changes of administration repeatedly undercut even cautious progress.

The twelve-day war exposed the vulnerability of Iran’s strategy and the limits of U.S. military pressure. Washington can continue a policy of isolation, allowing Israel to carry out occasional precision strikes, but that offers no sustainable solution. The alternative is to use the outcome of the campaign as a chance to return to negotiations and rebuild relations. However difficult the past may be, it should not dictate the future.

After 9/11: A Brief Window of Cooperation and Its Collapse

After September 11, it briefly seemed that relations could change. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and President Mohammad Khatami condemned the attacks, and demonstrations of solidarity with Americans took place in Iranian cities. Interests aligned: the destruction of al-Qaeda and the containment of the Taliban, who in 1998 in Mazar-i-Sharif killed up to eleven Iranian diplomats and journalists.

Iran had long supported the Northern Alliance, the main counterweight to the Taliban. In 2001, terrorists linked to al-Qaeda, posing as journalists, assassinated Ahmad Shah Massoud—the legendary leader of the Alliance. For Tehran, the rise of radical Sunnis represented a direct threat to its interests and security.

Iran—what seems unthinkable today—assisted the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps shared intelligence, provided logistics, and facilitated coordination with the Northern Alliance. American diplomats Ryan Crocker and Zalmay Khalilzad maintained contacts with Iranian representatives, possibly even with Qassem Soleimani himself.

Iran was eager to shape postwar Afghanistan. At the 2001 Bonn Conference, Tehran, together with the United States, backed an inclusive government, a compromise on the constitution, and election procedures. James Dobbins highlighted the crucial role of Javad Zarif in brokering the terms of the transition; Zarif in turn emphasized Soleimani’s contribution in persuading the Northern Alliance to make concessions.

This was a rare opening to improve relations. Joint work in Afghanistan could have been a ladder toward gradual normalization. Instead, in January 2002 President George W. Bush included Iran in the “axis of evil.” A month earlier Israel had intercepted a shipment of weapons bound for Hamas, heightening suspicions. In Washington, hardliners regained the upper hand.

Protests in Tehran against U.S. strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities. June 2025.

Confident of an easy victory in Afghanistan, Washington shifted its focus to preparing the invasion of Iraq. In the White House, Iran’s assistance was deemed irrelevant. In American eyes, continued support for proxies and “terrorist organizations” outweighed episodes of cooperation.

Washington’s rejection pushed the Islamic Republic toward a harder line. Confronted with U.S. troops in both Afghanistan and Iraq, Iranian elites concluded that dialogue offered no guarantees, while reliance on force was more dependable. Tehran began preparing for a prolonged confrontation with the United States on multiple fronts simultaneously.

In this way, Iran’s leadership managed to avoid what it most feared—complete isolation and the threat of regime change by force. But the price was steep: the region slid into prolonged rivalry with the United States and its allies, with conflicts flaring along the entire arc of instability—from Iraq to Lebanon and up to Iran’s own borders. In Washington, attitudes toward Tehran once again hardened into the logic of “containment through pressure.”

This strategy also reshaped the internal balance of power in Iran. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the Quds Force moved to the forefront, evolving from auxiliary tools into central levers of foreign policy. It was in the Iraq campaign that the Quds Force established itself as the instrument defining Tehran’s regional tactics.

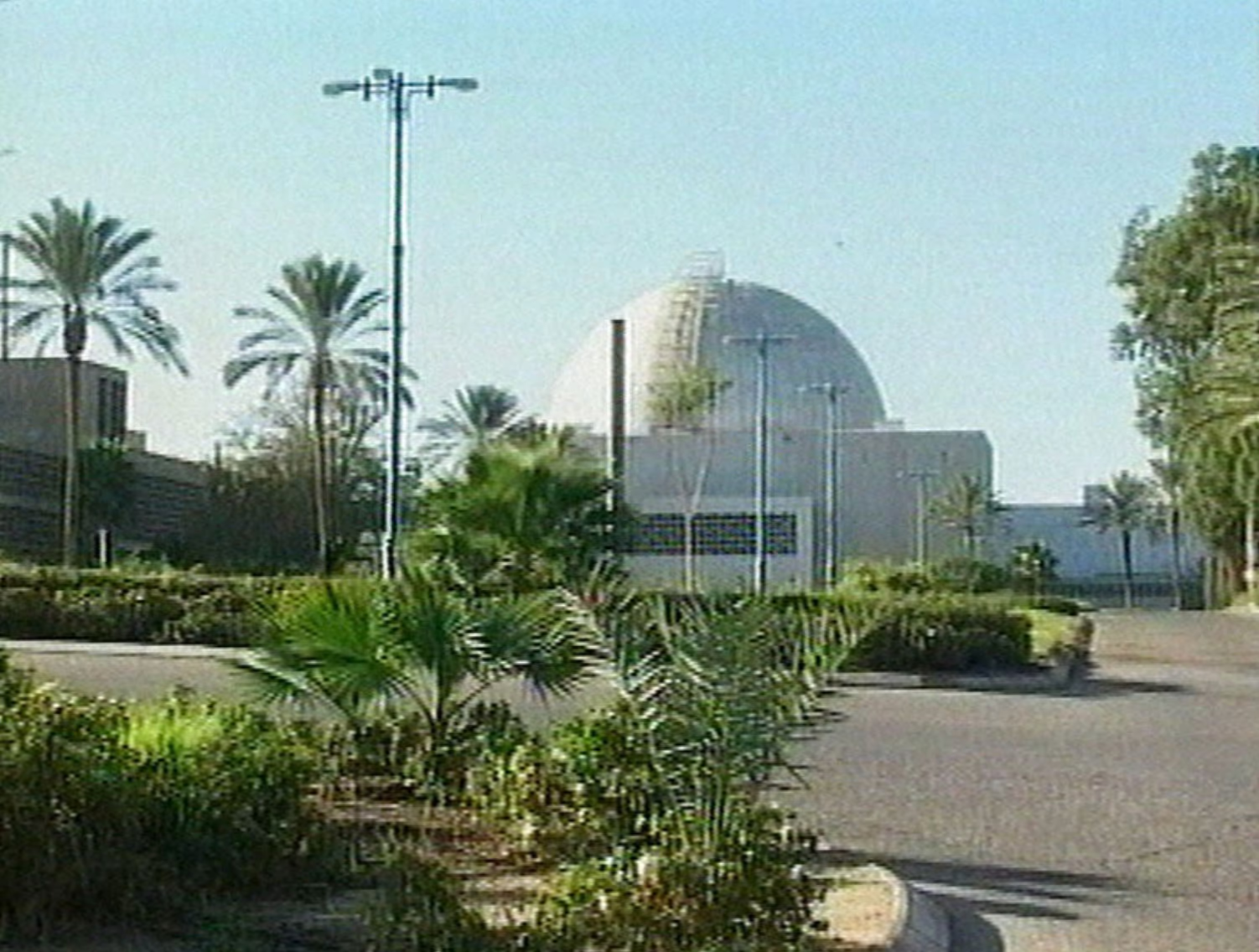

Fordow Is Iran’s Underground Nuclear Facility, Out of Reach for Israeli Strikes

Here Is What We Know About It

Israel Strikes Iran, Accusing It of Seeking Nuclear Weapons

Yet Israel Itself Has Long Possessed Them—Though Never Officially Admitted

Nuclear Program: Missed Deals and the Logic of Escalation

False hopes of rapprochement after 9/11 reinforced the conviction among Iran’s elite that the United States was not interested in an equal dialogue but sought to impose capitulation. Iran viewed U.S. bases in Afghanistan and Iraq as strategic encirclement and a threat.

Another turning point was the exposure of Iran’s nuclear ambitions. In 2002, opposition sources revealed covert facilities, just as the United States was preparing to invade Iraq. After George Bush branded Iran part of the “axis of evil,” trust collapsed.

But Washington failed to seize the opportunity for a diplomatic settlement. In 2003, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom secured a suspension of Iran’s modest nuclear program in exchange for limited sanctions relief. By 2004, however, Washington demanded Iran’s complete abandonment of nuclear activity without offering equivalent concessions.

In retrospect, that step proved a mistake. Without constraints the program gradually expanded. In 2005 Mahmoud Ahmadinejad came to power, pairing the drive to expand the nuclear program with hardline rhetoric and Holocaust denial, which deepened mistrust.

Had the United States backed the European initiative, Iran’s program would likely have remained limited and transparent—reducing threats. Tehran would have feared Washington less, pursued a different regional policy, and had stronger incentives to stick with diplomacy.

That calculation proved correct. By 2011 Iran’s program had grown substantially. Alarmed by the progress, Israel began threatening a preemptive strike. The Obama administration concluded that Iran could be contained only through a mix of pressure and negotiations.

Obama paved the way for talks by tightening sanctions in 2010 but avoiding regime-change rhetoric. He understood that ultimatums would not force Tehran to abandon nuclear ambitions; what was needed was a deal that served both sides and was backed by international monitoring.

In Tehran, Obama’s offer drew mixed reactions. Part of the elite—reformists and technocrats in particular—saw a chance to escape isolation; but within the Guardian Council, the clergy, and the security apparatus, skepticism prevailed: they believed the Americans could not be trusted.

Two years of tense negotiations involving Iran, the U.S., China, Russia, the U.K., France, and Germany culminated in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in 2015. In exchange for sanctions relief, Iran agreed to strict limits for at least a decade and rigorous international monitoring.

The agreement was a major step toward building trust. Had it stood the test of time, it could have been expanded—to cover restrictions on Iran’s missile program and regional policies. Sanctions relief and sustained cooperation would have given reformists a chance to strengthen their position inside the country.

Ali Khamenei at a mourning ceremony after the war between Iran and Israel. Tehran, July 2025.

Yet the expected thaw never materialized. The adoption of the JCPOA did not bring immediate changes to the Middle East. In Tehran, part of the elite still believed the U.S. remained an existential threat and had no intention of abandoning regime-change ambitions.

The Arab Spring further complicated the calculus. Uprisings across the region upset old balances and once again cast Iran as a threat. The loss of Syria would have meant a strategic defeat, weakening the “axis of resistance” and boosting Saudi Arabia’s influence.

In effect, Tehran chose a risky equilibrium: it scaled back its nuclear program under the JCPOA but expanded proxy activity and interventions in regional wars. Rivalry with the U.S. and its Arab allies—above all Saudi Arabia and the UAE—became systemic.

Iran’s foreign policy from 2014 to 2018 was marked by internal contradictions: diplomacy coexisted with escalation. As Javad Zarif noted, the country was in a "paralysis between diplomacy and the battlefield," and in the end the "battlefield" prevailed.

Had a different path been chosen, Iran’s nuclear program would have remained under strict control, and trust could have grown step by step. But in 2018 the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the deal. The result was heightened mistrust and eroded incentives for compliance.

A successful nuclear agreement could have reduced the perception of threat from Iran and opened space to address contentious regional initiatives—and perhaps even missile limitations. In the absence of guarantees that the deal would endure, that window closed.

Collapse of the JCPOA and Escalation: “Maximum Pressure,” Vienna, and the Turn to Moscow

The collapse of the JCPOA sharply escalated tensions between Tehran and Washington. The Trump administration launched its “maximum pressure” campaign, accompanied by harsh sanctions. Formally, the goal remained the same—to force Iran into a more “comprehensive” deal.

Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 election and the Democrats’ return to power raised hopes of restoring the agreement. During the campaign, Biden and other Democratic candidates said they were ready to return to the JCPOA provided Iran once again fully complied with it.

In April 2021, the United States agreed to negotiations in Vienna. By then, however, mistrust had deepened and opponents of the deal had gained strength in Tehran. The talks proved difficult—against the backdrop of Iran exceeding enrichment limits and announcing enrichment of uranium up to 60 percent, a step that brought the country significantly closer to the nuclear threshold.

It was in this context that Iran chose to support Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. Tehran established close military and intelligence cooperation with Moscow, provoking a sharp reaction from Europe and narrowing the space for diplomacy with the United States.

Iran’s Weakened Position and a Narrow Window for Diplomacy

In recent years, Iran’s regional standing has eroded significantly. After the Hamas attacks in October 2023, Israel systematically struck Iranian proxies, severely weakening Hamas in Gaza and effectively defanging Hezbollah in Lebanon. The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024 deprived Iran of a key ally and opened the prospect of a Sunni, anti-Iranian government in Damascus. In 2024–2025, Israel struck deep inside Iranian territory, exposing the vulnerabilities of its intelligence services and the limits of its missile and drone arsenal.

Donald Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio in Washington. June 2025.

If Trump does not want Iran to follow the path of North Korea—becoming a nuclear state—and if he wishes to avoid endless wars to contain Tehran, his administration will have to pursue a diplomatic solution. Iran, for its part, does not seek war and is not in a position to quickly build a credible deterrent arsenal—meaning negotiations remain the only viable option.

Within the Trump administration there is a conviction that the twelve-day war was a shock to Tehran and will force its leadership to think seriously about the future. But for Tehran to be willing to step back, diplomacy must deliver tangible, guaranteed benefits and be shielded from another breakdown. Paradoxically, it is the bombings that could open the way to a breakthrough—if both sides can break free of the inertia of past mistakes and agree on a roadmap covering the nuclear issue, the region, and sanctions.