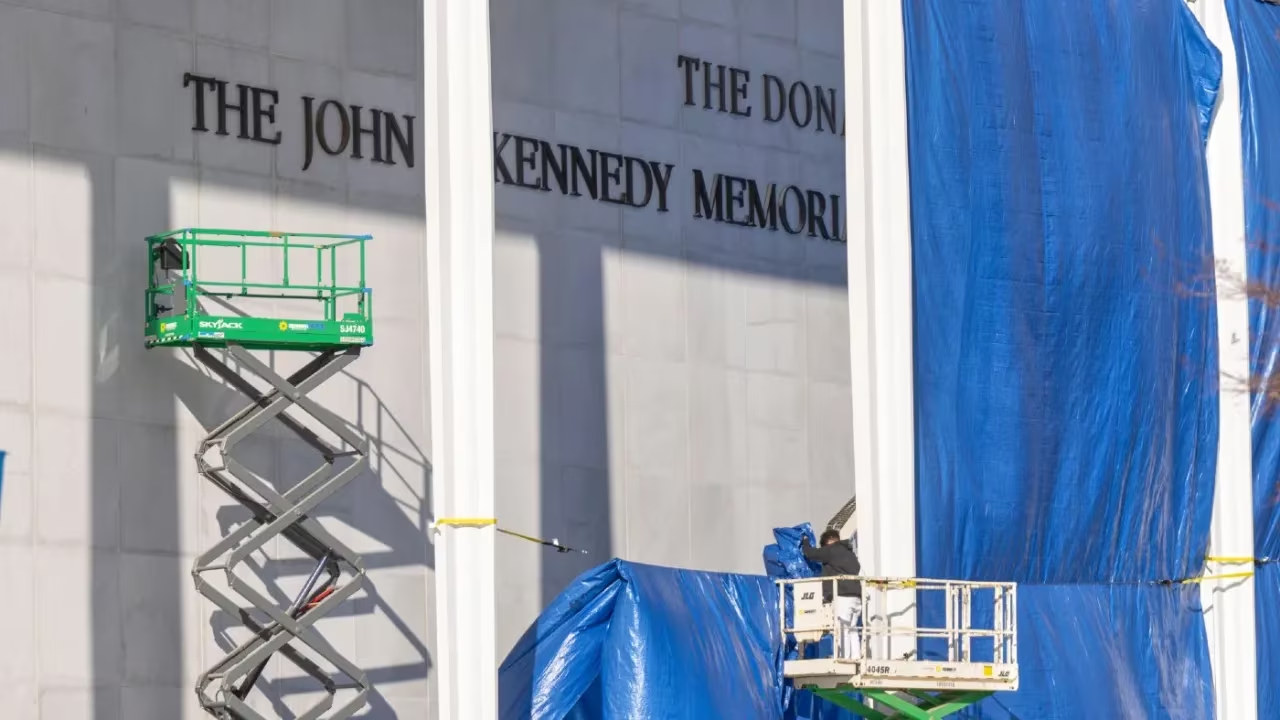

On December 19, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts formally became the “Donald J. Trump and John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts”—at least, that is what the new plaque affixed to the building now says. It was installed the day after the Center’s board of trustees, most of whose members were appointed by the sitting president, voted to approve the change. The decision was taken over the objections of the late president’s family and despite the fact that, as a matter of law, only Congress has the authority to alter the institution’s name as set out in statute.

Over the past year, the assignment and alteration of names has assumed a prominent place on Trump’s political agenda. Three days after the new sign appeared at the Kennedy Center, he announced plans to build a flotilla of new “Trump-class” battleships. Earlier this month, the U.S. Institute of Peace also underwent a renaming of its own, becoming the “Donald J. Trump U.S. Institute of Peace”.

When it comes to names, Trump clearly does not share Shakespeare’s notion that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. On the first day of his second term, he launched the project by executive order, declaring that “the names of our national treasures, including majestic natural landmarks and historic works of art, should honor the contributions of visionary and patriotic Americans from our country’s rich past”. Anticipating questions about the need to await congressional approval, he signaled that federal agencies could use the new names “during a transitional period”.

Defense Secretary—now referred to by the administration as the secretary of war—Pete Hegseth then joined the effort. As part of his campaign against “woke culture”, he began restoring to military bases names associated with Confederate generals. As NPR reported, he circumvented a 2021 congressional ban on such names by “identifying soldiers who shared the same surnames as Confederate figures and declaring that the bases were now named in their honor”. Hegseth may prove more successful in entrenching these names in everyday use than the Kennedy Center’s board has been in its attempt to change how people refer to that institution.

And yet the wave of renamings does not end there. It is entirely possible that Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport could, in time, become Donald J. Trump International Airport, and the city’s metro system “the Trump Train”.

What is at stake, however, is more than the gratification of presidential vanity. Such a policy fits squarely within the logic of how strong leaders act upon coming to power. As branding specialist Rebeca Arbona observes, “such renamings are not merely about words—they are about sovereignty. When the ruling power dictates what things are called, it shapes the framework through which people perceive and discuss them”.

Arbona may be right about the administration’s intentions, but not about the outcome. Anyone who has spent time on a university campus knows that students name places on their own terms, regardless of decisions handed down from above. Or step into a small town where a beloved hotel has been bought up and rebranded—the locals will still go on using the old name.

When society ignores new names, the project fails. Here, people possess a genuine lever of influence—what political scientist James Scott called the “weapons of the weak”. A change of name, by itself, does not guarantee a change in language, and no administration can fully control that. It is telling that the domain name TrumpKennedyCernter.org is already owned by one of the creators of the satirical animated series South Park.

There is therefore no reason for passive acquiescence. In everyday speech, the institution can continue to be called the Kennedy Center. News organizations, too, must decide whether to follow official directives or disregard them. That was the course taken by the Associated Press, which said it would continue to use the name Gulf of Mexico despite a January 20 order renaming it the “Gulf of America”. The agency reminded readers that “the Gulf of Mexico has borne this name for more than 400 years”, and that no president can erase such a history with a single stroke of the pen.

Major outlets, including The New York Times and The Washington Post, backed that stance. In October, journalist Joshua Benton analyzed several online databases and found that, ten months after the presidential order, the name “Gulf of Mexico” was still being used far more frequently.

It is ultimately up to people whether, a year from now, the names of the Institute of Peace and the Kennedy Center remain more familiar than those the Trump administration is trying to impose.