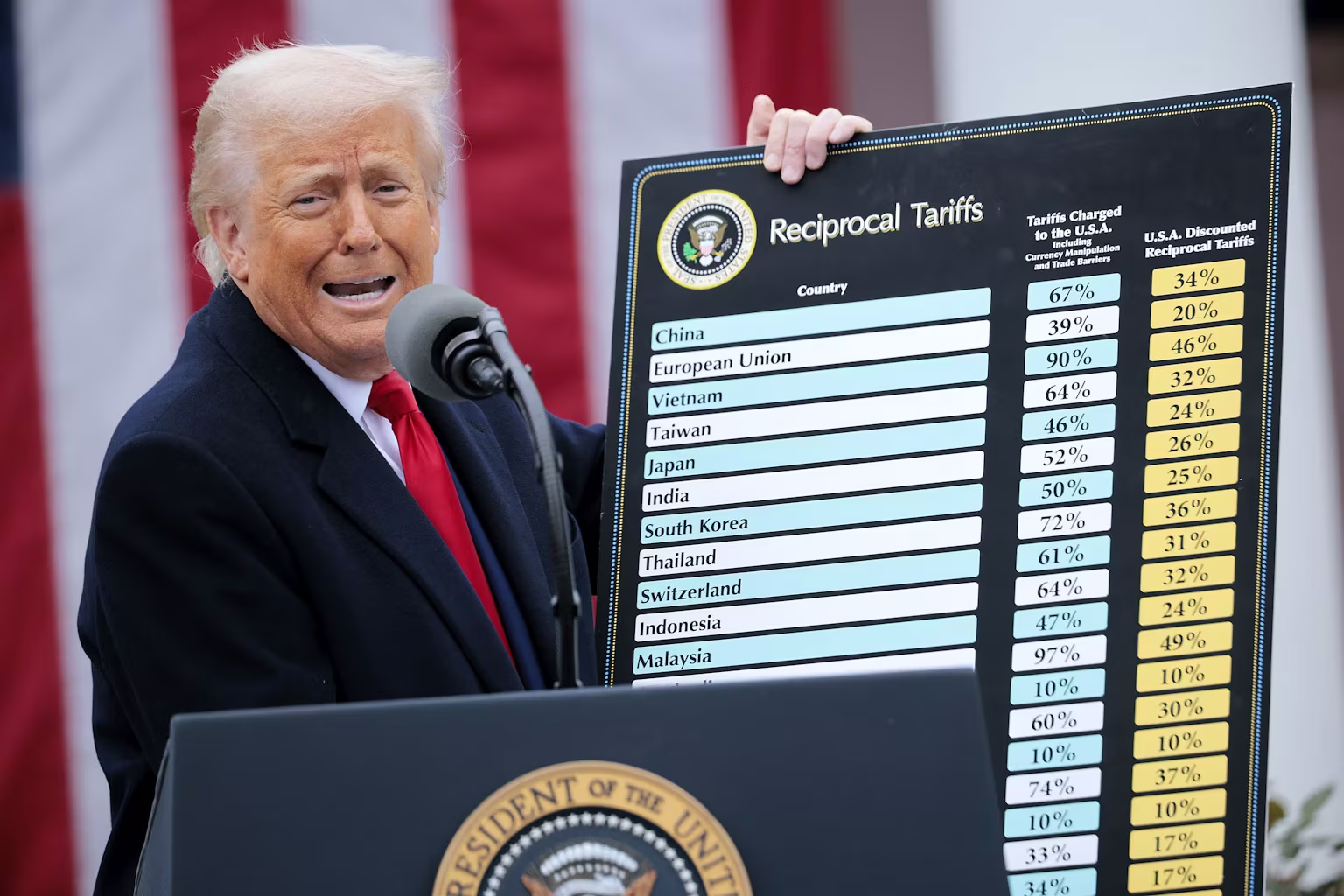

When Donald Trump unveiled his "Freedom Day Tariffs" this spring, only to back down days later amid turmoil on global markets, his team was quick to frame the move as temporary.

Officials claimed that a three-month pause would give the administration time to negotiate dozens of trade deals around the world. "We’re shifting into high gear," said White House trade adviser Peter Navarro on Fox Business Network. "We can close one deal a day."

But the 90-day delay announced by Trump is nearing its end, and the promised 90 deals have yet to materialize. The U.S. is once again preparing for a sweeping trade offensive targeting dozens of countries. Among the proposed measures: 27% tariffs on Kazakhstan, 47% on Madagascar, and 36% on Thailand.

"I’m not thinking about a pause," the president said at a press briefing earlier this week when asked about Wednesday’s deadline. "I’m going to send letters to many countries. I think you’re just beginning to understand how this process works."

Business leaders, lobbyists, economists, and investors might beg to differ. Even within Trump’s own administration, officials have at times struggled to keep up with his maneuvering. A new cliff edge is in sight, once again raising the familiar question: will he actually go through with it?

Tariff Policy of Trump

Who Invented Trump’s Tariff Policy That Shook Global Markets?

Meet Peter Navarro

He Did It

Trump Sends U.S. Trade Policy Back to the 19th Century with a Ridiculous Justification for Extreme Tariffs

A Tariff Farce With an Intermission

Why Is Trump Playing the Good Cop and the Bad Cop?

"I’d say he’s serious," said Marc Busch, professor of international trade diplomacy at Georgetown University. "He’ll likely spare countries that are genuinely negotiating in good faith. But starting July 9, we’ll be hearing about tariffs as steep as anything the U.S. has seen since the 1930s."

A few deals have been reached, easing tensions slightly. The first was a partial agreement with the United Kingdom, followed by a fragile truce with China and a deal with Vietnam. According to sources familiar with the negotiations, U.S. officials are also close to a framework agreement with the European Union.

Yet the deals that have been reached fall well short in both scale and substance compared to traditional free trade agreements, which typically take years to negotiate. "These aren’t real trade deals. They’re ceasefires," says Marc Busch. "Essentially, they’re procurement agreements that may—or may not—satisfy Trump for a while. They also come with elegant but non-binding language."

Even if Trump decides next week to extend the 90-day pause or begins to push through deals at a rapid pace, existing tariffs remain significantly higher than they were before his return to the White House. Their impact is already starting to show in the prices paid by American consumers.

"The U.S. economy is undoubtedly performing better than expected in the immediate aftermath of ‘Freedom Day,’" said Goldman Sachs President John Waldron. "But at the same time, there’s still an outlook for rising inflation this summer."

For mid-sized businesses, the consequences may prove especially painful. According to estimates by JPMorganChase, if the U.S. maintains a universal 10% tariff on all imports—along with 55% on goods from China and 25% from Mexico and Canada—the additional burden on such companies could reach $82.3 billion.

As analysts at the institute note, such enterprises "often play a vital role in regional economies and are embedded within broader production chains. Their financial distress can trigger a ripple effect, impacting other businesses and entire communities."

If the "Freedom Day tariffs" are reinstated after the pause expires, business costs will surge sharply. But even without further escalation, the existing tariffs still in place are already costing American companies significant sums.

The administration’s strategy—sharply raising tariffs and then partially rolling them back in exchange for deals—resembles, in Marc Busch’s words, "a retailer who hikes prices by 100%, then holds a sale offering 30% off." He adds: "It’s remarkable that we’re still talking about this. American businesses are already being forced to either absorb these tariffs themselves or pass the costs on to consumers."

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, despite public pressure from Trump, has maintained neutrality and kept interest rates unchanged, opting to wait and see how the White House's trade policy unfolds. He remains one of the few senior officials openly addressing the consequences of the tariffs.

"Someone has to pay for them," Powell said at a recent press conference. He explained how the cost of tariffs ripples through the supply chain—from manufacturers to end consumers. "At every step, companies will try to shield themselves from those costs. But in the end, part of the tariff is passed on to the consumer. We know this—businesses confirm it, the data shows it. That was true in the past, and it will be true again."

Trump, however, sees things differently. He insists that tariffs are a tax paid by other countries—not by American companies and their customers.

Regardless of the decisions made in the coming days, many analysts believe that key measures introduced in recent months—particularly the universal 10% tariff—are likely to stay in place for the long term.

"We believe that high, broad-based tariffs are likely to remain because, of all the trade policy tools announced, they’ve proven the most effective at generating revenue," says Michael Pearce, deputy chief U.S. economist at Oxford Economics. "Given the fiscal challenges that lie ahead, future administrations will find it very hard to walk away from that source of income."