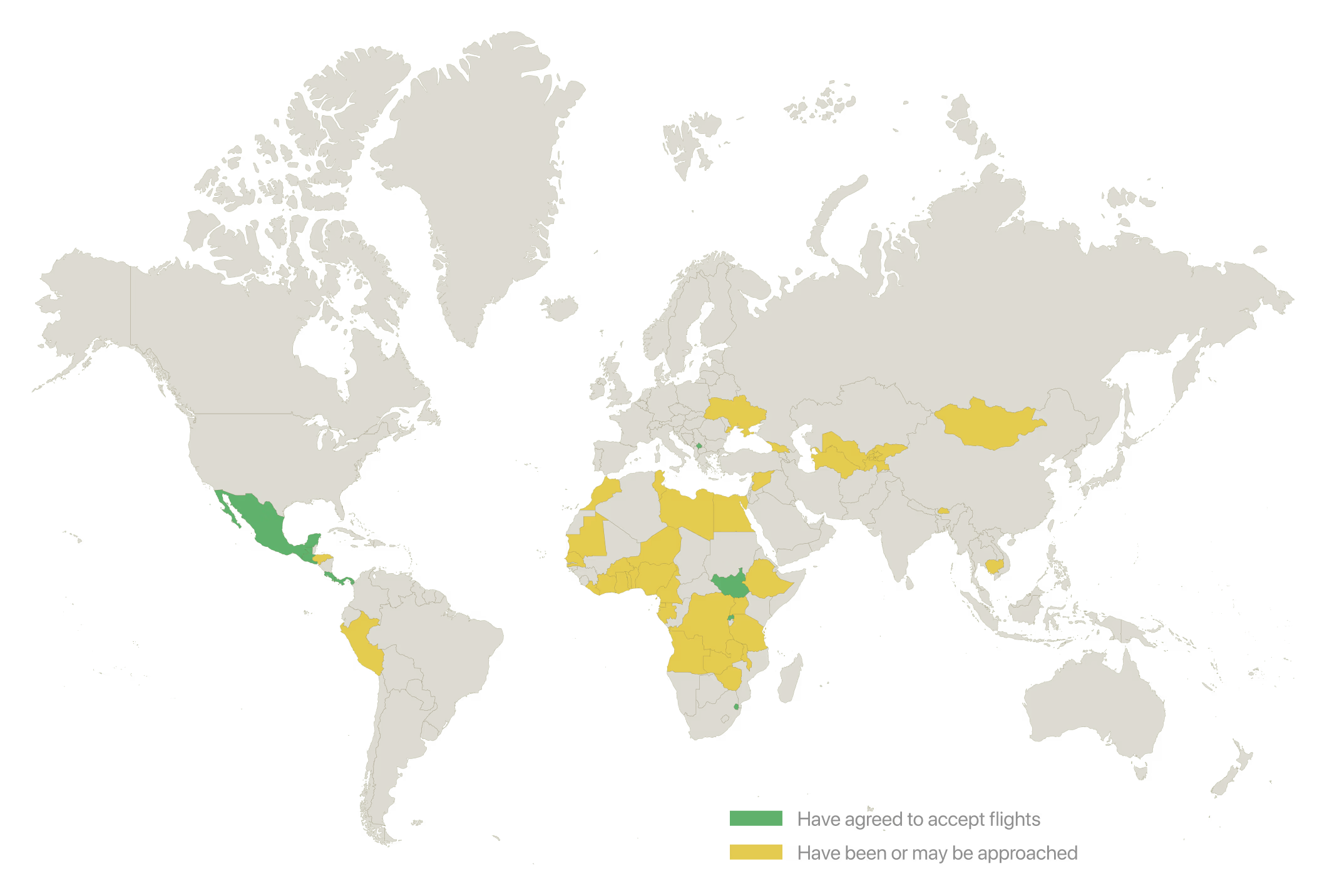

With Donald Trump’s return to the White House, his administration has launched a sweeping overhaul of immigration policy, focusing on fast-track deportations, bypassing legal procedures, and striking deals with third countries willing to take in migrants with no connection to them. After the U.S. Supreme Court in June allowed the resumption of removals without a mandatory delay for appeal, the White House stepped up negotiations with dozens of countries. According to The New York Times, the U.S. has approached or plans to approach roughly 51 countries. The goal is to build an infrastructure for mass deportations—including to places the migrants have never set foot in.

Agreements have already been signed with several countries, including some of the world’s poorest and least stable. On July 16, the U.S. deported five migrants to Eswatini—from Cuba, Jamaica, Laos, Vietnam, and Yemen. The Department of Homeland Security said the group included individuals convicted of murder and child rape. In March, 238 Venezuelans were sent to El Salvador under the Alien Enemies Act. They were accused of ties to terrorism and gang activity, but CBS News reported that 75% had no criminal record. By the end of April, Mexico had accepted about 6,000 non-Mexican migrants. President Claudia Sheinbaum described it as a humanitarian gesture—despite the fact that nearly 39,000 people had been deported from the U.S. to Mexico since the beginning of the year. In February, Guatemalan President Bernardo Arévalo agreed to accept migrants as a temporary transit measure, emphasizing that it did not constitute asylum. By then, Costa Rica had already taken in around 200 people, including 81 children and two pregnant women. President Rodrigo Chaves framed it as a duty to help “our economically powerful brother to the north.” In return, the U.S. committed to covering the costs of migrant care.

Panama became a transit hub in February—in exchange for U.S. funding. The country received deportees from Iran, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and China. In April, the U.S. paid Rwanda $100,000 to take in one Iraqi national. Under the terms of the agreement, Kigali agreed to accept ten more. In July, eight deportees—including citizens of Cuba, Laos, Mexico, Myanmar, and Vietnam—were sent to South Sudan after spending several days at a temporary holding center in Djibouti. In June, Kosovo agreed to temporarily host 50 migrants. According to sources, the deal was part of broader U.S. diplomatic efforts to strengthen international recognition of Kosovo’s independence.

Countries That May Accept Deportees from the U.S.

According to Tom Homan, the administration’s "border coordinator," the top priority is to sign as many agreements as possible to ensure a continuous flow of deportations. As Axios notes, some of the destination countries cannot be considered safe: Libya and South Sudan remain mired in long-term instability. Nevertheless, the White House views the policy as effective and as a demonstration of the "political will" to overcome all legal and logistical barriers.

At the same time, the administration has expanded its internal infrastructure for fast-track migrant detention. On July 3, a temporary tent camp named Alligator Alcatraz began operating in Florida. It got its name due to its location deep in the swampy Everglades region, which is indeed home to alligators. The camp was built on the site of a former airfield in just eight days and operates under a program that allows the federal immigration service to delegate part of its authority to state governments. This option was introduced in a 1996 law but had rarely been used until now. Since the 2024 election, the number of such agreements has surged—currently, they are in effect in 30 out of 50 states.

The migrant detention facility in Ochopee, Florida, was hastily constructed ahead of Donald Trump’s visit.

Officially, detention for the purpose of deportation is a civil procedure. However, conditions at Alligator Alcatraz differ little from those in a prison. Reporters from The New York Times and The Washington Post interviewed migrants held there. According to them, the tents leak—especially during the rainy season—mosquitoes are everywhere, showers are on a strict schedule, lights stay on all night, food is scarce, and medical care is nearly nonexistent. There are no books, TVs, or recreational areas. Legal aid is unavailable: the facility is isolated from nearby cities, and most detainees have no contact with the outside world. Moreover, Alligator Alcatraz does not appear in the official immigration detention database, making it impossible for families to locate missing relatives.

According to official data, the camp holds about 900 people, mostly from Latin American countries. Around 60% have prior convictions or are under investigation; the rest are being held solely for immigration violations. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis promotes the facility as an example of an "innovative and cost-effective" approach. However, critics argue that cost savings are achieved primarily by omitting basic infrastructure: the camp was set up without permanent construction, wastewater is hauled away by tanker trucks, and all supplies are brought in. Despite these measures, the facility’s operating costs exceed $450 million per year—more than what is spent on federal detention centers.

Contracts for the construction and operation of the camp were awarded without competitive bidding. They went to companies linked to Republican Party donors. The American Civil Liberties Union has filed a lawsuit, arguing that conditions at the camp violate basic human rights, including the right to legal representation. Many families are unable to locate their relatives, who have effectively "disappeared" from the federal system’s database.

Trump personally visited Alligator Alcatraz shortly after it opened. Federal officials have emphasized that the project was implemented entirely at the state level and that responsibility lies with Florida authorities. Still, the very existence of such a facility—alongside a series of international deals—illustrates a new principle: with enough political will, any legal norm or geographic boundary can be bypassed.

Not Their Home

Venezuela Accuses El Salvador of Torturing Deported Migrants

Caracas Demands Investigation Into Bukele’s Actions, Citing Beatings, Sexual Violence and Solitary Confinement

The U.S. Plans to Tax Migrant Remittances

Millions of Families in Africa and Latin America Risk Losing a Vital Lifeline

The Hell of Waiting

Inside a Dutch Refugee Camp Where More Than 20 Suicides Have Occurred

EU Migration Policy Shifts Sharply to the Right

Even Centrists Now Back Deportations, Offshore Camps, and Rewriting the European Convention