On September 2, U.S. forces struck a vessel that, according to the Trump administration, was carrying cocaine and belonged to members of the Tren de Aragua gang. The initial strike did not sink the boat, and, as media reported, two survivors remained on board. A second strike—the defining moment of the entire operation—destroyed the vessel completely, killing everyone on it. The incident has since raised questions about the legality of the mission, the Pentagon’s role, and the legal rationale the White House invokes in explaining what happened.

Members of the Trump administration defend the September 2 follow-up strike on the drug-running vessel, which killed the survivors of the first attack. They say the objective was to eliminate the boat entirely and that the Pentagon had issued internal legal authorization for such an operation.

White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told reporters on Monday that Admiral Frank Bradley, who oversaw the mission and ordered the second strike, acted to ensure the vessel would be sunk. «Admiral Bradley acted squarely within his authority and the law by issuing an order that ensured the destruction of the boat and the removal of a threat to the United States of America», Leavitt said.

Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told a cabinet meeting on Tuesday that the second strike «sank the boat and eliminated the threat», while emphasizing that his own role had been minimal.

By framing the strikes as directed at the vessel itself, officials echo language from a classified memo by the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) that authorized the mission. That framing allows them to ground the legality of the attack in the strongest possible terms after questions began to mount around the episode.

According to three lawyers familiar with the document, the OLC memo argues that the United States may use lethal force against unidentified cocaine-carrying vessels because cartels use the proceeds to finance violence. The rationale is that the cartels are engaged in an «armed conflict» with U.S. partners in the region, and that, under collective self-defense, Washington may destroy cocaine aboard such vessels to cut off revenue streams used to purchase weapons.

Most crucially for the administration, the OLC memo contends that the near-certain death of people on board does not make the vessel an unlawful military target.

The legal assessment rests on conclusions drawn by U.S. intelligence, set out in a classified annex of the OLC opinion’s «statement of facts» as well as in a presidential national security memorandum on the use of military force against drug cartels dated July 25. Although the documents remain classified and have not been publicly referenced before, they are known to contain detailed information, including estimates that each such vessel typically carries roughly $50 million worth of cocaine.

The OLC memo has faced sharp criticism from independent legal experts, given the scant public evidence that cartels finance armed violence specifically through drug trafficking rather than the other way around.

Even so, the Trump administration’s account fits within the framework laid out by the OLC memo and provides a plausible legal justification—one it can rely on to fend off potential congressional or criminal inquiries amid lawmakers’ calls for greater scrutiny.

That rationale is likely to be echoed by Bradley himself—a longtime special operations officer who now heads U.S. Special Operations Command as a vice admiral—when he appears Thursday morning before senior Democrats and Republicans on the House and Senate armed services committees.

Until this week, Hegseth had spoken far more freely about the purpose of the second strike. At various points, he suggested that killing people could be justified if they were linked to cartels. «Every trafficker we kill is affiliated with a Designated Terrorist Organization», Hegseth wrote on X on Friday as he tried to rebut a Washington Post report claiming he had ordered the killing of survivors after the boat strike.

He later escalated that rhetoric, posting a parody book cover depicting Franklin the Turtle, the cartoon character, firing on drug traffickers from a helicopter. The cover read: «Franklin Takes the Fight to the Narcoterrorists».

Pentagon Reports New Strikes on Drug Cartel Boats in the Pacific

According to the U.S. Defense Department, Fourteen People Were Killed

U.S. Expands Anti-Drug Campaign in Latin America

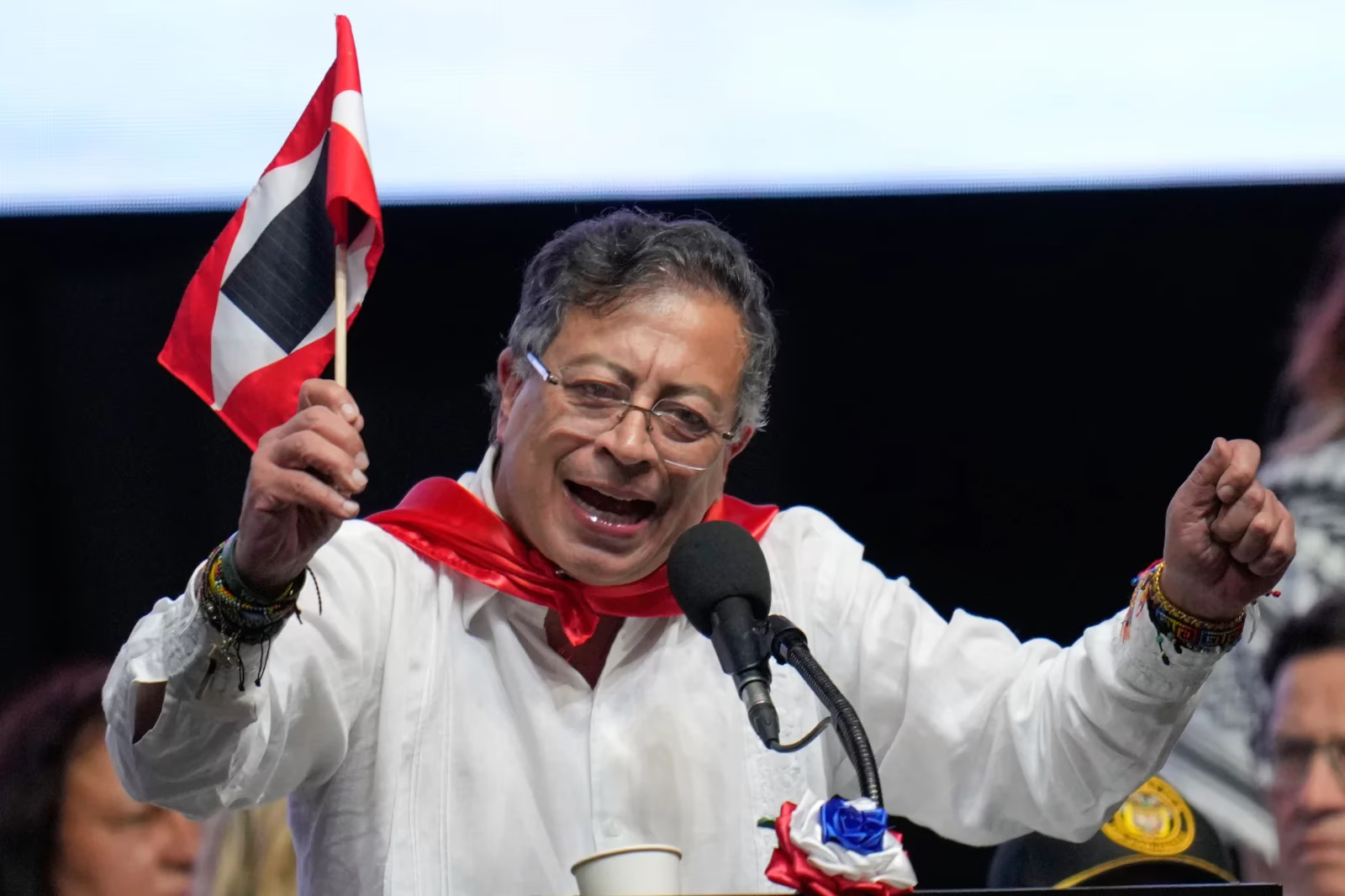

Trump Accuses Colombia’s President of Cartel Ties and Increases Military Presence off the Region’s Coast

Yet nothing of the sort appears in the OLC memo: it examines only the legality of targeting the boats and explains that rationale through standard scenarios outlining what military forces may strike even under the so-called laws of armed conflict.

For example, a munitions plant supplying an army is typically considered a lawful military target. But its employees, if they are not part of armed groups, remain civilians—and killing them would be unlawful, one expert noted.