On May 8, the anniversary of Nazi Germany’s surrender, 49 of Germany’s leading companies issued a collective statement openly acknowledging their historical responsibility for the Nazi rise to power in 1933 and for corporate complicity in sustaining the regime. This message is not a symbolic gesture of remembrance, but an attempt to show that elite silence can cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

Against this backdrop, the silence of international brands with close historical ties to the Third Reich stands out in sharp contrast. Coca-Cola, which cultivated ties with Nazi institutions and created the Fanta brand in 1940, has never issued an apology. Associated Press, which supplied imagery for Nazi propaganda, has defended its actions as a necessity for operating in a closed society—but likewise refuses to accept responsibility. These examples highlight a stark divide: some draw lessons from history, others prefer to forget it.

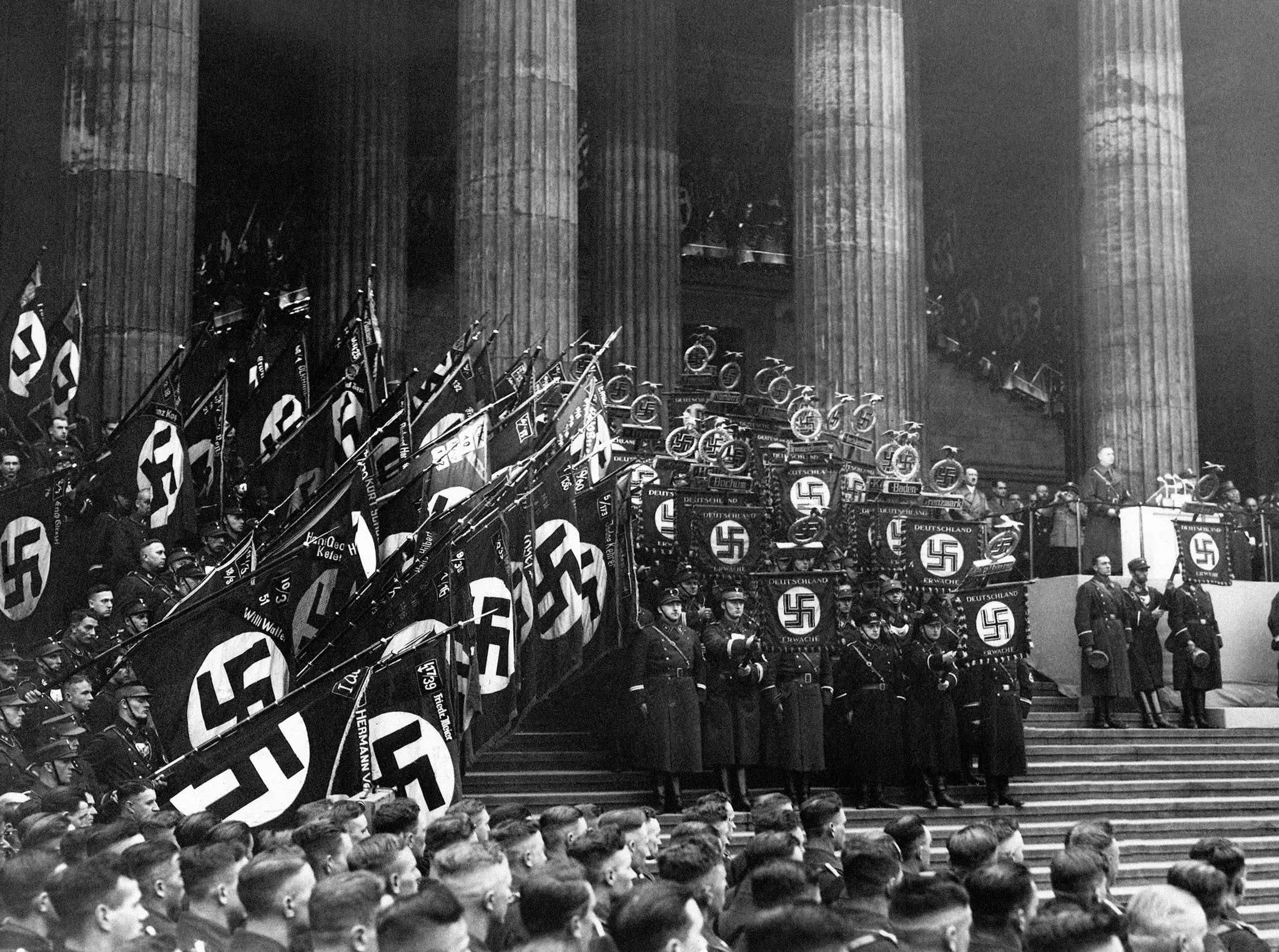

"Without the failure of the political, military, judicial, and economic elites of the time, Nazi rule would not have been possible," the statement reads. "German companies contributed to the consolidation of their power. In pursuing their own interests, many became entangled in the regime."

The statement was issued to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II and was initiated by Bayer CEO Bill Anderson, following his participation in a January 27 memorial ceremony at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. He later reached out to other business leaders with a call to speak with one voice. Among the companies that joined were Siemens, Deutsche Bank, Volkswagen, BASF, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Lufthansa, Deutsche Telekom, and many others.

Herbert Bayer produced materials for the German government for a decade. 1933.

Adolf Hitler’s Mercedes. 1936.

Adolf Hitler visiting German workers at a Siemens factory. 1933–1935.

The signatories stress that the role of modern business is not to distance itself from the past but to confront it openly. "Today, we, German companies, accept the responsibility to make the memory of Nazi crimes visible. These crimes remind us how fragile democracy is," the statement reads. "Together, we stand against hatred, against exclusion, and against antisemitism. This past cannot and will not be put behind us."

Beyond its historical message, the document calls for the defense of the values made possible only after the collapse of the Third Reich—rule of law, European unity, and freedom.

"Democracy survives through participation—and dissent. It demands conviction and courage. In 1933 and after, far too many remained silent, turned away, and said nothing. This is where our responsibility begins—for the past, the present, and the future."

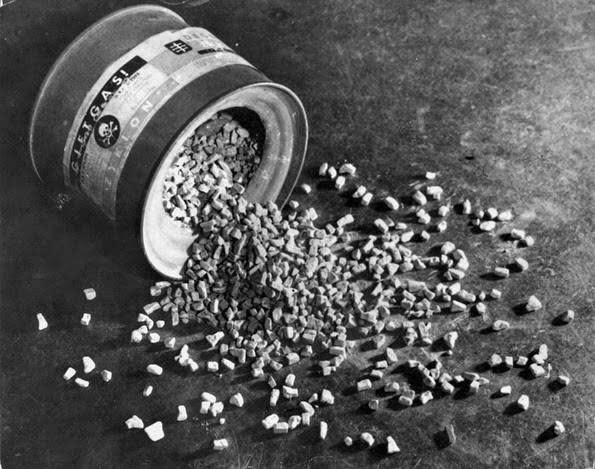

Zyklon B insecticide. Bayer was involved in the development of the gas used by Germany in the death chambers. 1940.

The joint statement was published simultaneously in Die Zeit, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung—a gesture underscoring the scale and gravity of the initiative. It marks the first time in modern history that nearly fifty of the country’s largest companies have so openly reflected on their role in the darkest chapters of the past and called for vigilance in the present.

Accountability That Never Came: Coca-Cola, Associated Press, Hugo Boss, and Kodak Still Avoid Acknowledging Their Role in the Nazi Regime

The public reckoning by German companies stands in stark contrast to the silence of many international brands whose histories are closely linked to the Nazi regime. Some of them have yet to assume any moral responsibility for their actions.

Kodak, for instance, continued doing business with Nazi Germany through its subsidiaries in Switzerland and Portugal even after the U.S. entered the war. These branches purchased equipment from the Third Reich and supplied photographic and radio gear that served the needs of the German military. The company’s German division used the labor of more than 250 concentration camp prisoners. After the war, Kodak reintegrated its German branch and contributed to a compensation fund—but never issued a formal apology.

Associated Press—one of the largest news agencies in the U.S.—operated in Germany from 1933 under the strict terms set by the Nazi regime. It dismissed Jewish employees, allowed SS personnel into its newsroom, and provided photographs that were later used in antisemitic propaganda. The agency maintains that staying active in Germany enabled it to inform the world about developments under the regime. But it has never explicitly acknowledged its role or apologized for its contribution to Nazi propaganda.

Hugo Boss manufactured uniforms for the SS, the Hitler Youth, and other Nazi institutions. Starting in 1940, its factories used forced labor from concentration camp inmates and prisoners of war. The company’s founder was a member of the Nazi Party and a financial backer of the SS; he was later declared a regime collaborator. Yet the brand—now a global fashion house—contributed to a compensation fund only in 1999 and never issued a formal expression of regret.

Even Coca-Cola—a symbol of American culture—was not exempt. Its German branch, led by Max Keith, actively adapted the brand to align with Nazi ideology, cooperated with the Hitler Youth, and, amid a shortage of imported syrup, created a new beverage: Fanta, which gained popularity during the war years. After the Nazi surrender, the branch was brought back under corporate control, and Keith—despite his close ties to the regime—was reinstated as head of Coca-Cola’s German operations.

Nazi German military uniforms designed and produced by Hugo Boss.

Associated Press photograph taken in Berlin during the Nazi regime. In 1933, Germany enacted a law that significantly restricted press freedom, yet AP continued operating in the country until 1941.

Business and Authoritarianism in the 21st Century

The statement by German companies serves as a reminder that responsibility for 1933 lay not only with politicians, but also with the business community that chose not to intervene. Which raises an urgent question: what is happening today?

In many countries, large corporations continue to compromise with governments—not under duress, but by choice. In China, Apple agreed to censorship in the App Store and removed dozens of VPN applications. Tesla relocated user data storage to China in compliance with government demands. Meta, responding to Donald Trump’s return, abandoned independent fact-checking and adapted its platform to political expediency. All three retained market access, but lost their claims to political neutrality.

In Russia, until the full-scale war against Ukraine began, dozens of Western companies—including BP, Shell, TotalEnergies, Auchan, Leroy Merlin, and Unilever—did business closely intertwined with state structures. Even after 2022, many did not leave. In 2024, Unilever admitted that its Russian subsidiary was paying taxes, some of which supported military mobilization. Nevertheless, as of 2025, the company continues to operate in the country.

These examples show that even in democratic societies, market logic can override principle. Just as it did ninety years ago, companies often prefer to preserve the status quo rather than confront power. Silence today is not the absence of speech, but the absence of action. It manifests in contracts, agreements, localization, and strategic neutrality. It is the very "turning away" described in the statement—not refusal, but detachment, for which there will eventually be a price.

Echoes of War

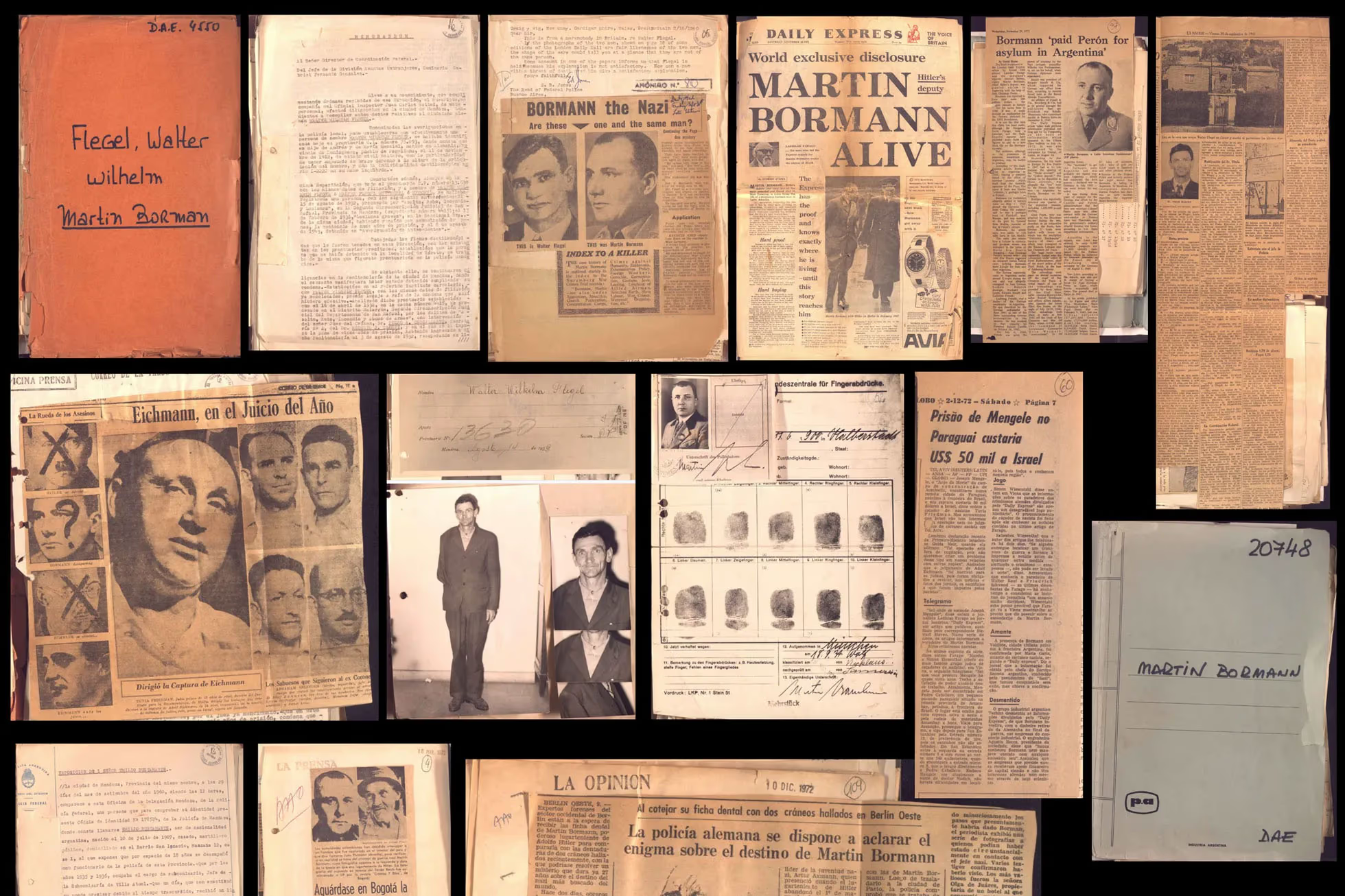

Argentina Opens Nazi Escape Files

New Documents Reveal How Intelligence Services, the Church, and the State Helped Hide War Criminals

The War Being Fought Again

World War II no longer belongs to the past. It has once again become a battleground—not for territory, but for the right to define the truth. For Russia, it is the last legitimizing myth. For Ukraine, it is a space to assert the freedom to be itself