A bold and controversial scientific project has been launched in the United Kingdom to create the fundamental building blocks of human life from scratch—an effort that experts say may be the first of its kind in the world. Until now, such research was considered taboo, primarily due to fears that it could lead to the creation of so-called "designer babies" or trigger irreversible changes affecting future generations.

However, the world’s largest medical charity—Wellcome Trust—has allocated an initial £10 million in funding for the project, arguing that the potential benefits outweigh the risks. Among them is the promise of breakthroughs in treating previously incurable diseases.

Dr. Julian Sale of the Medical Research Council’s Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, who is involved in the project, told the BBC that this marks the next giant leap forward in biology.

"The possibilities are limitless. We’re talking about therapies that could allow people to age without disease, to age more healthily," he explained. "Our goal is to use this technology to create disease-resistant cells that could be used to regenerate damaged organs—such as the liver, the heart, and even the immune system."

Scientists will begin developing tools to synthesize increasingly long segments of human DNA.

Nevertheless, critics warn that the project opens the door to potential misuse—from the creation of genetically modified humans to the development of biological weapons.

"We like to think all scientists are driven by good intentions, but science can also be used for harm, including in military contexts," said Dr. Pat Thomas, director of the advocacy group Beyond GM.

Details of the project were revealed by the BBC on the 25th anniversary of the completion of the Human Genome Project—a landmark initiative that first decoded the structure of DNA and was also funded by Wellcome.

Every cell in the human body contains a DNA molecule that holds all the genetic information it needs. DNA is built from just four basic elements—A, G, C, and T—repeating in various combinations. Despite this apparent simplicity, these sequences encode all the physical traits that make us who we are.

The Human Genome Project gave scientists the ability to "read" the full set of human genes—like a kind of barcode. The new phase, known as the Human Synthetic Genome, potentially represents a fundamentally different level: researchers will now be able not only to read the DNA molecule, but also to synthesize its fragments—and eventually, perhaps, entire molecules from scratch.

The scientists’ first goal will be to develop methods for creating increasingly large fragments of human DNA—ultimately aiming to synthetically reproduce a full human chromosome. Chromosomes contain the genes that control the body’s development, repair processes, and essential functions.

These artificial structures can then be studied and tested to better understand how genes and DNA as a whole regulate the workings of our bodies. According to Professor Matthew Hurles, director of the Wellcome Sanger Institute—which decoded the largest share of sequences during the Human Genome Project—this research has direct medical relevance.

"Many diseases are caused by genetic malfunctions. Understanding how DNA works can open the door to new treatments," he noted. "By synthesizing DNA from scratch, we gain the ability to test new theories and approaches. Right now, we can only do that by modifying existing DNA in living organisms, which severely limits what we can explore."

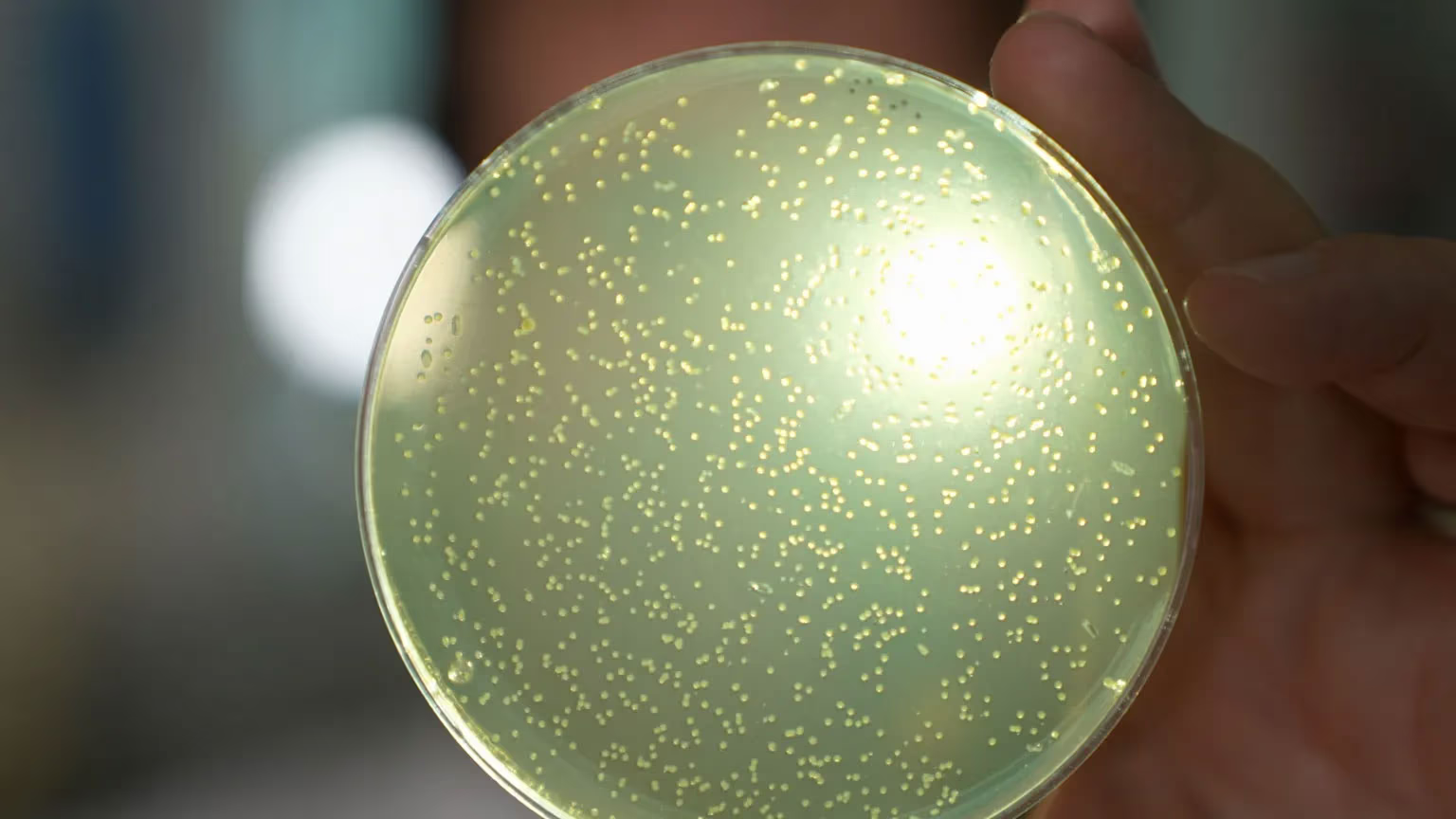

The project will be conducted exclusively in test tubes and petri dishes—creating synthetic life is not part of the plan. Nonetheless, the technologies involved will give researchers an unprecedented level of control over living human systems.

While the official aim of the project is medical breakthroughs, the technologies themselves could potentially be used for other purposes. Professor Bill Earnshaw—one of the UK’s leading geneticists and a pioneer in artificial chromosome creation—warned that this could include attempts to develop biological weapons, "enhanced" humans, or even organisms containing human DNA elements.

"The genie is already out of the bottle," he told the BBC. "Even if we impose restrictions now, any organization with the right equipment could, if it wanted to, synthesize just about anything. And stopping that would be nearly impossible."

Another concern is the potential commercialization of the technology. According to Pat Thomas of the Beyond GM campaign, the question of ownership is especially troubling.

"If we learn to create synthetic organs—or even synthetic humans—who will own them? Who will hold the rights to the data generated from these experiments?"

So why did the Wellcome Trust decide to fund the project despite all the potential risks? According to Dr. Tom Collins, who oversaw the decision, refusing would have meant stepping away from the future.

"We asked ourselves: what is the cost of inaction? Sooner or later, these technologies will be developed anyway. If we take the lead now, we can do it as responsibly as possible—openly addressing the ethical and moral challenges."

Alongside the scientific component, the project will include a dedicated social science program led by Professor Joy Zhang, a sociologist at the University of Kent. "Our aim is to involve experts, sociologists, and—most importantly—the public in discussing how this technology is perceived, what benefits it might bring, and what concerns it raises," she explained.

Countdown to Collapse