In late May 2025, Étienne-Émile Baulieu—renowned physician and scientist, and the creator of the first medical abortion pill—passed away in Paris at the age of 98. Baulieu’s life could have ended much earlier: as a young Jewish man during the Nazi occupation of France, he joined the Resistance. Later, he again found himself at risk—this time as a scientist. After the release of mifepristone, the drug that would permanently change reproductive medicine, he became the target of threats. Yet the violence never materialised.

Baulieu lived a long life, remaining steadfast in his convictions to the very end. He was the man who gave millions of women around the world a safe way to end a pregnancy—and never stopped fighting for their rights.

From an Early Age, Baulieu Resisted Dictatorships—From the Nazis and Vichy to the Soviet Invasion of Hungary

In 1942, fifteen-year-old Étienne Blum was living near Grenoble, in Nazi-occupied France. His Jewish heritage made his very existence a mortal risk. But beyond the threat to his life, what he witnessed stirred outrage—and he decided to join the Resistance. Blum distributed underground pamphlets, transported weapons, and took part in attacks on German vehicles.

On one occasion, while sitting in a café, Gestapo officers entered. Blum realised they had come for him and managed to escape through the back door. Without alerting his family, he fled the city and later secured false papers for himself and his relatives. To conceal his origins, he adopted a new name—Étienne-Émile Baulieu. It was under that name that the world would come to know him.

After his escape, he settled in the city of Annecy and continued his work with the Resistance. Following the liberation of France, Baulieu took part in the kidnapping of Charles Marion—a Vichy official sentenced to death. Marion was killed by his captors, and Baulieu documented the operation by filming it with a camera.

He remained committed to leftist ideals and, like many in his circle, joined the Communist Party. But in 1956, he left in protest after Soviet troops crushed the Hungarian uprising. By then, political activism had receded into the background: he had married at twenty, was raising a family, and studying at medical school.

Étienne-Émile Baulieu Enrolled in Medical School on a Whim, Became a Professor by Thirty—And Everything Changed After a Trip to Costa Rica

Étienne-Émile Baulieu’s father, Léon Blum, was a physician. He specialised in kidney disease and treated patients with diabetes. Léon was among the first doctors to use insulin after its discovery, and even treated King Fuad I of Egypt, who suffered from the condition.

Yet Baulieu remembered little of his father—he died when the boy was just three years old. His mother, Thérèse Blum, blamed the medical profession for her husband’s death, convinced he had contracted an illness from a patient. She was firmly opposed to the idea of her son becoming a doctor.

Nevertheless, Étienne-Émile enrolled in medical school—not out of conviction, but more in solidarity with a friend. He quickly grew interested in the field, and to somewhat appease his mother, he decided to study biochemistry as well—a discipline that, unlike clinical medicine, did not involve contact with patients.

Baulieu became deeply engaged in science, especially under the guidance of his mentor, biochemistry professor Max-Fernand Jayle. It was Jayle who encouraged the young researcher to focus on sex hormones—a field so fruitful that by the age of 30, Baulieu had already become a professor of biochemistry.

His achievements drew international attention. The prominent American hormone researcher Seymour Lieberman invited Baulieu to spend a year working in the United States. But obtaining a visa was not straightforward—his communist past raised concerns. He was granted entry only under the administration of John F. Kennedy.

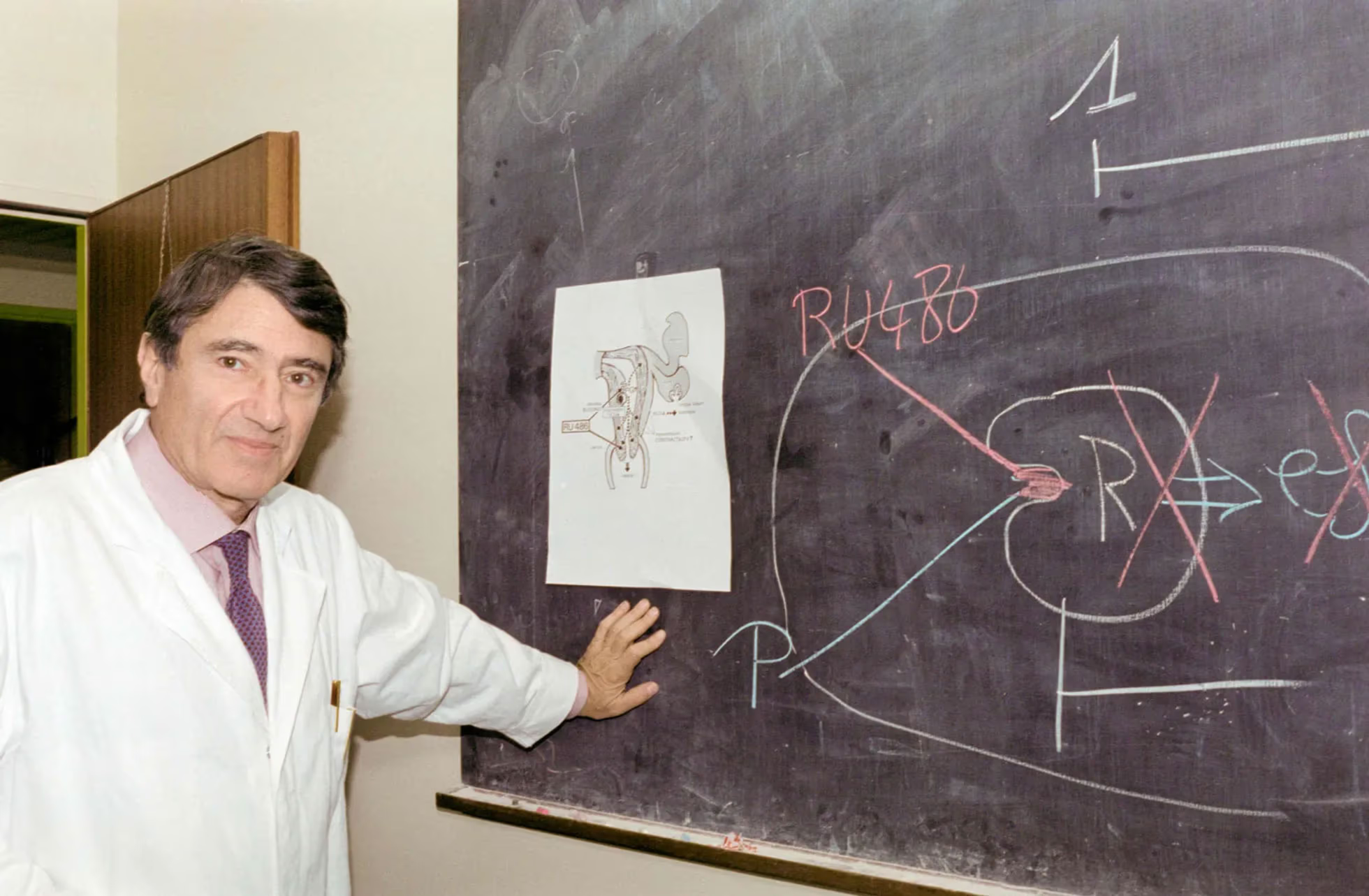

Étienne-Émile Baulieu.

While working in the United States, Baulieu met Gregory Pincus—one of the four pioneers behind the development of the first oral contraceptive. This encounter played a key role in shaping Baulieu’s future scientific and ethical convictions.

Pincus persuaded Baulieu to join him on a trip to Costa Rica to observe clinical trials of birth control pills. The experience left a deep impression. Baulieu saw firsthand how access to oral contraception could transform women’s lives—how it expanded their freedom of choice and control over their own bodies.

After that, he decided to redirect his scientific work. From that moment on, his main goal became developing tools that would help women avoid pregnancy when they didn’t want it.

"I’m Not Against Children. But Women Die From Back-Alley Abortions. I Want Them to Have a Choice"

Gregory Pincus’s ideas resonated deeply with Baulieu—in large part because of how he was raised. His mother held feminist views, and he grew up in a household of women—two sisters and a grandmother—giving him early insight into the struggles women face in a patriarchal society. Baulieu believed that the right to end a pregnancy was a fundamental human right. "I want to help women," he told Science magazine. "I didn’t devote my life to abortion. I’m not against children. I have three of my own and seven grandchildren. But women die from unsafe abortions. Two hundred thousand every year."

In France, Baulieu worked within a government research institution while also serving as a consultant to the pharmaceutical company Roussel Uclaf. It was in a public laboratory that his team first identified progesterone receptors in the uterus—molecular "locks" with which the hormone progesterone interacts. Under normal conditions, progesterone binds to these receptors to initiate and sustain processes necessary for pregnancy.

Baulieu concluded that if a compound could be created to bind to those same receptors without activating them—a kind of "false key"—it would block progesterone’s effect and thus terminate pregnancy. This idea became the basis for a radically new type of medication.

In 1980, a chemist named Georges Teutsch at Roussel Uclaf synthesized a molecule designated RU 486. The company considered several possible applications, but it was Baulieu who insisted on testing it as a drug for medical abortion—at a time when women around the world had access only to surgical procedures.

Clinical trials involving women seeking to terminate pregnancies were conducted in Switzerland—Parisian doctors had refused to participate. The results were encouraging: the drug proved effective in nine out of eleven cases.

Packaging of RU 486 (mifepristone) used during clinical trials.

A follow-up study in Sweden introduced a second drug—prostaglandin, which induces uterine contractions—administered after RU 486, later named mifepristone. This two-step protocol significantly improved the method’s effectiveness and remains the standard practice in medical abortion today.

"They Compared Me to Mengele, but I Knew Women Were Suffering Without Safe Options"

In France, mifepristone was officially approved in 1988, triggering an immediate wave of protest. Opponents accused Étienne-Émile Baulieu of genocide—one Canadian billboard even featured his photo alongside the charge. He was compared to Mengele and Hitler, with some claiming he would cause more deaths than Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Hitler combined. During one visit to the United States, the threats became so serious that he had to hire a bodyguard.

For Baulieu, the issue was personal. As a medical student, he had overheard surgeons refusing anesthesia to women who had undergone illegal abortions. "Teach her a lesson she won’t forget," he recalled one doctor saying. That memory became part of his moral imperative.

"Methods that make abortion less traumatic and less dangerous for women’s health always meet fierce resistance from those who want to ban it," he later said. "But what they’re really after is to make women suffer—and to punish them for their choices."

Protest outside the Roussel Uclaf office. The sign reads: "Stop the French Pill RU 486." Paris, 1993.

Protest outside the Roussel Uclaf office. The sign reads: "Abortion Kills Children." Paris, 1993.

The protests targeted not only Baulieu but also the pharmaceutical company Roussel Uclaf. Activists accused it of "turning the womb into a crematorium," sent dozens of angry letters daily, and staged loud demonstrations outside the company’s headquarters.

The company was owned by the German conglomerate Hoechst, which was deeply uneasy about such associations—particularly given the dark chapters of its own past, including cooperation with the Nazi regime, which it preferred not to revisit publicly. References to Mengele and death camps cast a dangerous and unwanted shadow over the corporation’s reputation.

Under public pressure, just one month after the drug’s approval in France, Roussel Uclaf announced it was halting sales of the medication.

Nonetheless, the company had no intention of giving up its patent on RU 486—the molecule that would later become known as mifepristone. Roussel Uclaf saw it as a promising compound not only for reproductive medicine but also for cancer research and the treatment of certain chronic conditions. The patent secured exclusive rights for future development.

During a protest outside the Roussel Uclaf office, opposing slogans are on display: "American Women Want RU 486" and "Abortion Kills Children." Paris, 1993.

The fate of mifepristone was ultimately determined by the intervention of French Health Minister Claude Évin and the support of the medical community. Under pressure from gynecologists and the public, Évin declared: "I cannot allow the abortion debate to deprive women of a drug that represents a step forward in medicine. From the moment the government approved this medication, RU 486 became the moral property of women, not just the property of a pharmaceutical company." Following his statement, mifepristone was returned to the market.

Baulieu himself played a crucial role in persuading the medical community of the drug’s importance and securing its approval in other countries. He organised meetings, gave interviews, and addressed doctors and politicians alike. Yet he never sought personal gain: Baulieu did not earn a single cent from the sale of mifepristone. Everything he did was driven by the conviction that women should have the right to make a safe and informed choice.

Rights That Still Need Defending

Trump Revokes Emergency Abortion Protections in Hospitals. The Rule Had Required Doctors to Save Women With Life-Threatening Complications

The Oldest Law Fades Into History

England and Wales Decriminalize Abortion

Support for Abortion Rights Is Declining Among Men

Women Have Become More Vocal Since the Repeal of Roe v. Wade

A Child Was Born in Atlanta to a Woman Declared Brain-Dead

Life Support Was Maintained Due to the State’s Abortion Ban