The U.S. tariffs imposed in April sparked more than just market volatility—they called into question the very foundations of global production. An estimated 300 million companies around the world are interconnected through 13 billion logistical links. All of them now face profound uncertainty.

But the current turbulence is only the latest episode in a series of disruptions that have shaken the global economy over the past five years. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020, supply chain breakdowns have forced economists to rethink conventional assumptions about how global production is organized.

Shortages of goods—from hand sanitizers, which depend on imported specialty chemicals, to aircraft (in 2024, Airbus faced a shortfall in key components)—have exposed the fragility of a system in which products often cross borders multiple times at different stages of assembly.

These disruptions have also cast doubt on existing methods for measuring economic activity.

Although the architecture of global production has been radically reshaped by trade and technology, statistical systems still rely on methodologies developed in the mid-20th century. These approaches remain focused on demand—both current and historical—but offer little insight into the economy’s ability to adapt to stress, that is, the state of supply.

As a result, a significant portion of today’s economic activity—especially in advanced economies—goes unmeasured. Estimates suggest that up to 80% of such processes fall outside standard metrics. Official statistics still emphasize industrial sectors, which are easier to track but no longer drive most economic growth.

In a world of growing interdependence and recurring external shocks, policymakers need new tools—ones that can track not just consumption but also the resilience of supply chains, and register forms of economic activity that didn’t exist when the current statistical system was designed.

This calls not just for an update of indicators, but for a fundamental rethink of how data is collected—from risk assessments in supply chains to the inclusion of intangible assets and service components in the measurement of growth and inflation.

Building a statistical model capable of correcting the blind spots of today’s system is not an academic exercise. It is the foundation for formulating viable economic policy in an age of crises.

A 20th-Century System

At the heart of the international system for measuring economic activity lies the System of National Accounts (SNA)—a set of statistical standards used to calculate GDP. Developed in the 1940s with the involvement of John Maynard Keynes, it was originally designed to manage wartime economies: the Allies needed to balance domestic consumption with the production of military equipment.

After the war, the system was adapted for peacetime and gradually became the universal foundation of economic statistics. Today, it is revised under UN supervision roughly once a decade—usually in response to structural shifts such as the growing importance of the financial sector. Yet the revision process remains highly inertial: any changes require international consensus, which makes the system resistant to reform—and vulnerable to reality.

The current version of the SNA still effectively captures the mid-20th-century economy: one dominated by industry, with production largely confined within national borders, and where digital infrastructure played only a supporting role.

The most recent updates introduced a few incremental additions—but did not rethink the system’s fundamental premises.

The core problem is not technical backwardness, but the logic of the system itself: the SNA captures outcomes well but does not help explain their causes or provide tools for adaptation. It is more an instrument of postmortem analysis than real-time diagnosis.

The Economy Has Changed—But the Statistics Haven’t

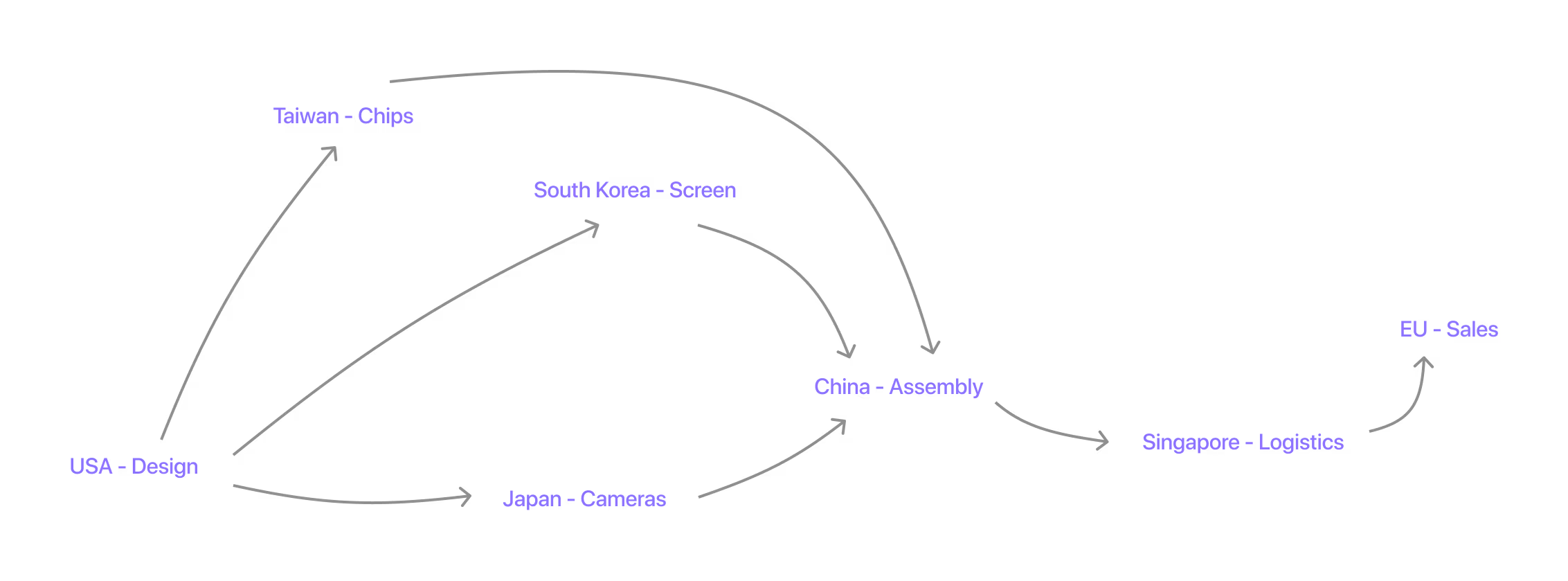

For nearly a century, the System of National Accounts has served as a universal language for measuring growth and comparing economies. But since the late 20th century, it has reflected the structure of the global economy less and less. Since the 1980s, vertically integrated firms—those that controlled everything from design to sales—have given way to flexible networks: designers, contractors, distributors, and service providers are now scattered across different countries and continents.

Where international trade once meant shipments of cars and refrigerators, it now involves the movement of components, intermediate goods, and data—crossing borders at every stage of assembly and logistics.

Global Supply Chain: A Smartphone's Journey From Idea to Sale in the EU

This is especially evident in sectors like electronics and pharmaceuticals, where contract manufacturing accounts for up to 20% of total output in the U.S. and the UK. At the same time, the physical product is increasingly bundled with services: Rolls-Royce, for example, doesn’t just sell engines to airlines—it sells access to real-time digital monitoring systems.

This model fueled growth: specialization, division of labor, and scale helped boost productivity. But it also made companies more vulnerable: dependence on a narrow set of foreign suppliers for critical components increased their exposure to external shocks.

That—more than just clogged shipping lanes—is what the pandemic laid bare.

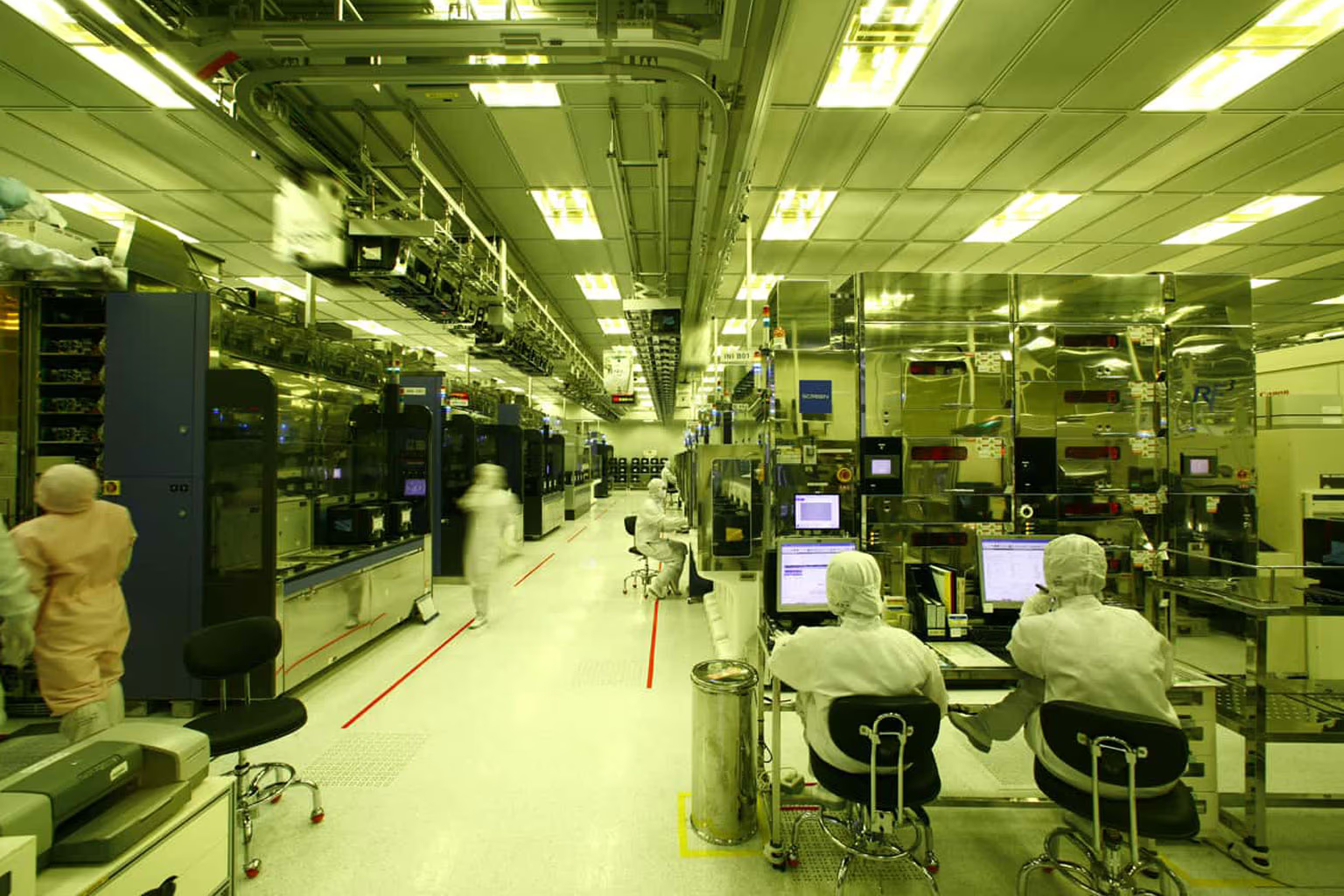

Clean room at a chip manufacturing plant: a line of engineers and microelectronic equipment.

Smartphone assembly line at a contract manufacturing plant in Shenzhen.

Where Traditional Statistics Fall Short

Conventional accounting methods were never designed for such a densely interconnected web of dependencies. The lack of reliable tools to assess supply-side dynamics makes it difficult to grasp the state of global supply chains—even under stable conditions, let alone during crises.

An equally profound gap lies in the system’s inability to capture the impact of technological shifts. For example, GDP statistics barely reflect the economic impact of cloud services, which have drastically reduced costs and increased flexibility for businesses. Likewise, the real value of big data—now a strategic resource for many industries—goes largely unmeasured: only capital expenditures on data centers are counted, not the value those assets generate.

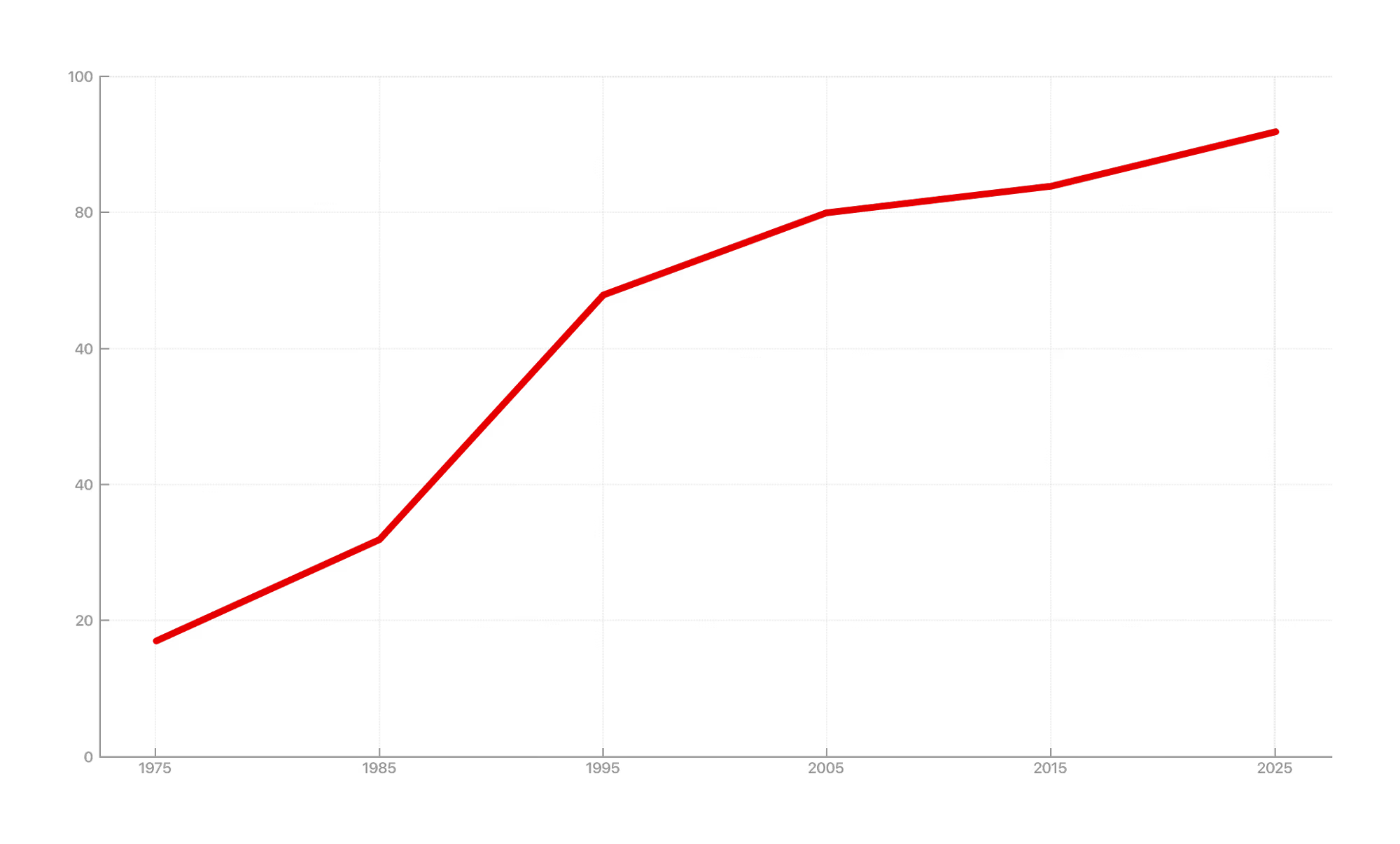

Growth of Intangible Assets in S&P 500 Companies (1975–2025), %

In recent decades, intangible assets—such as software, data, and brands—have become dominant. Estimates suggest they will account for over 90% of the total asset value of S&P 500 companies by 2025. Yet economic statistics still focus on factories, machinery, and warehouses.

Even among experts, there is no consensus on how to account for ubiquitous and free digital tools in the economy—from open-source software to foundational AI infrastructure.

The Ever Given tanker blocked the Suez Canal, highlighting just how fragile global supply chains are.

Empty supermarket shelves in London. 2020.

Attempts to Adapt

Some research institutions and central banks have begun developing their own experimental metrics. For instance, the Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, created by the U.S. Federal Reserve, was introduced in response to how post-pandemic logistical disruptions contributed to inflation.

Yet even these new tools do not capture risks to specific production nodes—such as the iPhone assembly chain or the distribution of rare earth components. Nor are there methods to register how digitalization and AI are reshaping trade dynamics, labor structures, or value creation chains.

Put simply, economic policy is increasingly being crafted without a map—neither for present conditions nor for what lies ahead.

Rethinking the Numbers

Developing statistics that reflect the real architecture of the global economy is an ambitious task—but not a utopian one. Economists such as Vasco Carvalho of Cambridge point to the potential of using tax records, payments data, and logistics flows to map production networks in real time. But that alone is not enough.

A true modernization of economic statistics must go beyond tracking shipments or new business models. It must be capable of measuring resilience, identifying vulnerabilities, and capturing future potential—alongside offering a more precise description of current activity.

In this context, growing attention is being paid to the concept of comprehensive wealth—a national balance sheet that includes both traditional and intangible forms of capital.

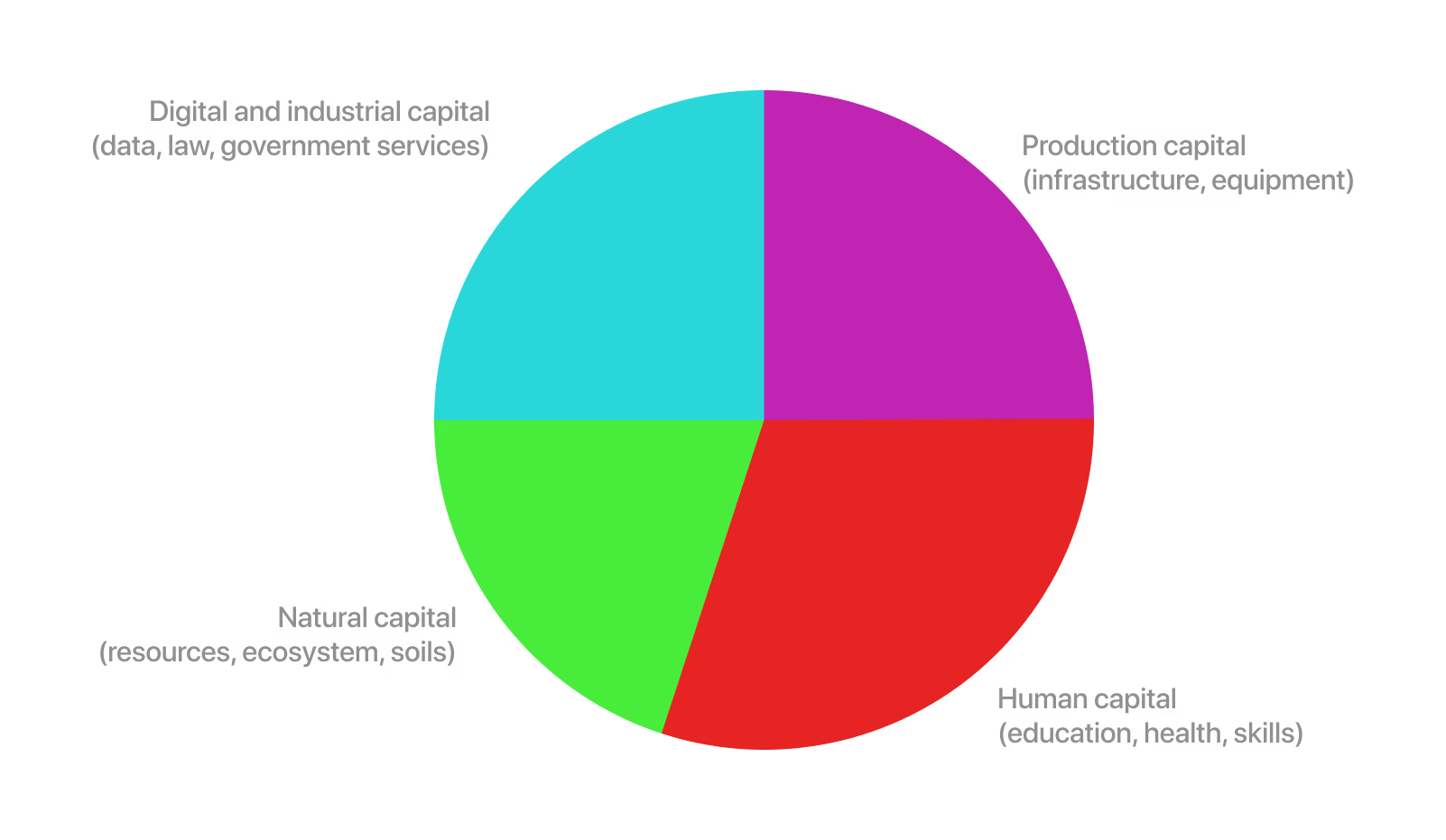

Structure of Comprehensive National Wealth

It’s not just about buildings, roads, and infrastructure—it’s also about what has long remained outside statistical spreadsheets:

• telecommunications networks, including their vulnerabilities;

• digital public infrastructure: cloud services, ID systems, payment gateways;

• volumes of accessible data—held both by the state and the private sector.

• telecommunications networks, including their vulnerabilities;

• digital public infrastructure: cloud services, ID systems, payment gateways;

• volumes of accessible data—held both by the state and the private sector.

This "digital stack" has already become a critical component of economic life—and at the same time, a source of new failure points. The resilience of any state striving for strategic autonomy increasingly depends on its ability to measure and manage such risks.

Capital You Can’t Touch

A comprehensive national balance sheet is incomplete without accounting for human capital—education levels, health, and workforce skills. These directly affect productivity, innovation, and fiscal trajectories.

Natural capital is equally important. While current statistics may include strategic resources like rare earth metals, they often overlook "silent" assets: soil quality, biodiversity, and the resilience of water systems—all of which shape the future of agriculture and climate stability.

Lastly, institutional capital must be considered—the legal and political architecture within which the economy operates. As Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson emphasize, it is strong institutions—contract enforcement, rule of law, property rights—that determine whether a country is capable of sustained growth.

Modern statistics make no distinction between jurisdictions with "extractive" institutions—where power is concentrated in the hands of elites and economic activity is suppressed—and those where institutions foster entrepreneurship and human capital accumulation. That distinction is crucial. And it, too, must be measured.

Time to Count Differently

Moving from traditional consumer and business surveys to new sources of information would mark a cultural revolution for the conservative world of official statistics. But without this transformation, it is impossible to build a more accurate and timely picture of productivity and economic vulnerabilities. The challenge is compounded by the fact that, in most countries, national statistical agencies have faced budget cuts—a trend that began after the 2008 global financial crisis.

What’s needed is not just modernization, but a coordinated international effort to establish new standards and definitions. In an era of declining response rates and rising "survey fatigue" among businesses and citizens, shifting toward data collected automatically and in real time is no longer a choice—it is a necessity.

The irony is that the very technological shifts that rendered the old statistical model obsolete now offer the tools to rebuild it. Much of the needed information already exists—in tax records, banking transactions, point-of-sale systems, satellite imagery, logistics trackers, and sensor networks. The task is to learn how to see it as part of the statistical system.

Experimental initiatives like the Anthropic Economic Index are already attempting to track the adoption of artificial intelligence across sectors. This is an early attempt to capture one of the defining technological transformations of our time—one that so far remains almost invisible in macroeconomic reporting.

A New Challenge—and a New Opportunity

Global production networks are under immense pressure. Against this backdrop, it is only natural that policymakers want more than retrospective analysis—they want real-time insights into the economy’s condition, including its vulnerabilities, risks, and structural shifts.

In the 1940s, the demands of total war led to the creation of the System of National Accounts—a tool that enabled governments to manage mobilized economies. Today, in an era of trade conflicts, geopolitical instability, and technological transformation, the world once again needs a measurement system capable of capturing real dynamics.

Until that system exists, our understanding of the global economy will remain fragmented—and decisions will be made in the dark.

Economy Without a Manual

An Economy Where No One Pays Now

Global Debt Is Growing Faster Than the Ability to Service It

The End of Globalization as We Knew It

Economics in the Age of New Borders

The U.S. Economy as a Source of Global Instability

American Policymaking Increasingly Resembles That of Emerging Markets