The travel journal Capture the Atlas hosts what is perhaps the most unusual contest in the world of astrophotography: every year, all participants photograph the same subject—the Milky Way. Yet despite this shared focus, no two images are alike. The variety of locations, compositions, techniques, and perspectives makes each frame unique—and that’s precisely the point. Beneath this visual diversity lies a constant question: what does humanity really know about its own galaxy, and how has that knowledge changed over the past century?

The contest’s finale offers a chance not only to glimpse some of the planet’s most spectacular spots for viewing the Milky Way, but also to reflect on that question. And along the way, to share a few practical tips for those just beginning to photograph the night sky.

Let’s start with a reminder: the Milky Way is the galaxy that contains our Solar System. It was through observing its bright band across the night sky that the story of astronomy began—and without understanding its structure, the science of the Universe would be impossible to imagine.

The Milky Way—or as the ancient Greeks called it, the "milky circle" (Κύκλος Γαλαξίας)—was known to humanity long before we began asking questions about its nature. It can be seen with the naked eye on a clear night, and for centuries, cultures around the world created myths to explain its origin. But the scientific study of the Galaxy began, as so much in astronomy does, with Galileo. He was the first to turn a telescope toward the night sky and discovered—what now seems almost self-evident—that the Milky Way’s glowing band is made up of stars.

Before that, it was far from obvious. The Galaxy appears to the human eye as a hazy glow—one that could easily be imagined to come from some other source. While a large part of the Milky Way’s mass does consist of interstellar gas and dust, these components don’t emit light—on the contrary, they absorb it. If not for them, the Galaxy’s band across the sky would shine even brighter.

Less intuitive is the fact that just a century ago, the Milky Way was believed to mark the edge of the known Universe. In 1880, Irish astronomy popularizer Agnes Mary Clerke confidently wrote: "No competent thinker, surveying the facts at hand, would venture to assert that a single nebula can be a stellar system comparable in scale to the Milky Way." In other words, science at the time assumed that all observable stars belonged to one single galaxy—ours.

The only exception were the Magellanic Clouds, which puzzled astronomers—and for good reason: they would later be confirmed as independent galaxies, the Milky Way’s nearest satellites. And yet it is striking that even in the 1910s, as Albert Einstein was formulating general relativity—the theory that predicted gravitational waves and lensing, and still underpins modern cosmology—he believed the Milky Way was all there was.

The turning point came on the morning of January 1, 1925. At a meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Edwin Hubble presented observations of the Andromeda (M31) and Triangulum (M33) nebulae, showing that these objects lay far beyond the Milky Way and were themselves vast stellar systems. In a single moment, the Universe expanded to unimaginable proportions—and humanity, in cosmic terms, was no longer at the center, but on the edge. To understand how we got to that conclusion, we need to go back a little further.

Edwin Hubble’s discovery was made possible by a technical breakthrough: in 1918, the Mount Wilson Observatory in Southern California began operating the world’s largest telescope at the time—a 100-inch reflector. For decades, it remained unmatched in capability. It was with this instrument that Hubble managed not only to capture images of distant nebulae, but to resolve individual stars within them, including those whose properties made it possible to measure their distance.

These were Cepheids—stars whose brightness varies in a regular, predictable cycle. Astronomers already knew that there was a direct relationship between the period of a Cepheid’s fluctuations and its intrinsic luminosity. This meant that by measuring the period, one could determine how much light the star actually emitted. Comparing that value with how bright the star appeared from Earth allowed for an accurate calculation of its distance—much like estimating how far away a candle is if you know how brightly it burns up close.

In one such observation, while studying Cepheids in the Triangulum Nebula (M33), Hubble arrived at a stunning result: the distance to these stars was 285 kiloparsecs—around 929,000 light-years. That figure far exceeded even the boldest estimates of the Milky Way’s size and left no doubt that M33 was not part of our galaxy, but an independent stellar system of comparable scale.

It thus became clear: the Milky Way is just one of countless galaxies in the Universe. What had once appeared from Earth as faint smudges or spiral patches were, in fact, entire worlds containing billions of stars. And although more than 120,000 such objects had already been catalogued, it was only after Hubble’s work that their true nature became understood.

And Now—The Photographs!

"One in a Billion," International Space Station.

"A Sea of Lupines," Lake Tekapo, New Zealand.

"Universo de Sal," Jujuy Province, Argentina.

"Echiwile Arch," Ennedi Plateau, Republic of Chad.

"Evolution of Stars," Otago Region, New Zealand.

"Lake RT5," Zanskar, Himalayas.

"Blosoom," Hehuan Mountain, Taiwan.

"Stairway to Heaven," Madeira, Portugal.

"Glimpse of Colors," southern coast of Crete, Greece.

"A Stellar View From the Cave," Saint-Raphaël, France.

"Fortress of Light," Jujuy Province, Argentina.

"Double Milky Way Arch Over Matterhorn," Zermatt, Switzerland.

"Galaxy of the Stone Array," Moeraki Boulders, New Zealand.

"Bottle Tree Paradise," Socotra, Yemen.

"The Wave," Coyote Buttes slope, Utah, USA.

"Diamond Beach Emerald Sky," Great Ocean Road, Australia.

"Boot Arch Perseids," Alabama Hills, California, USA.

"Cosmic Fire," Acatenango Volcano, Guatemala.

"Tololo Lunar Eclipse Sky," Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile.

"Tololo Lunar Eclipse Sky," Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, Chile.

"The Night Guardians," Easter Island, Chile.

"Winter Fairy Tale," Dobratsch Nature Park, Austria.

"Spines and Starlight," Kanaan, Namibia.

"Starlit Ocean: A Comet, the Setting Venus, the Milky Way, and McWay Falls," California, USA.

"Un Destello en la Oscuridad," Matarraña, Spain.

Far from Earth

Still Alone in the Universe

Why the SETI Project Hasn’t Found Extraterrestrial Life in 40 Years?

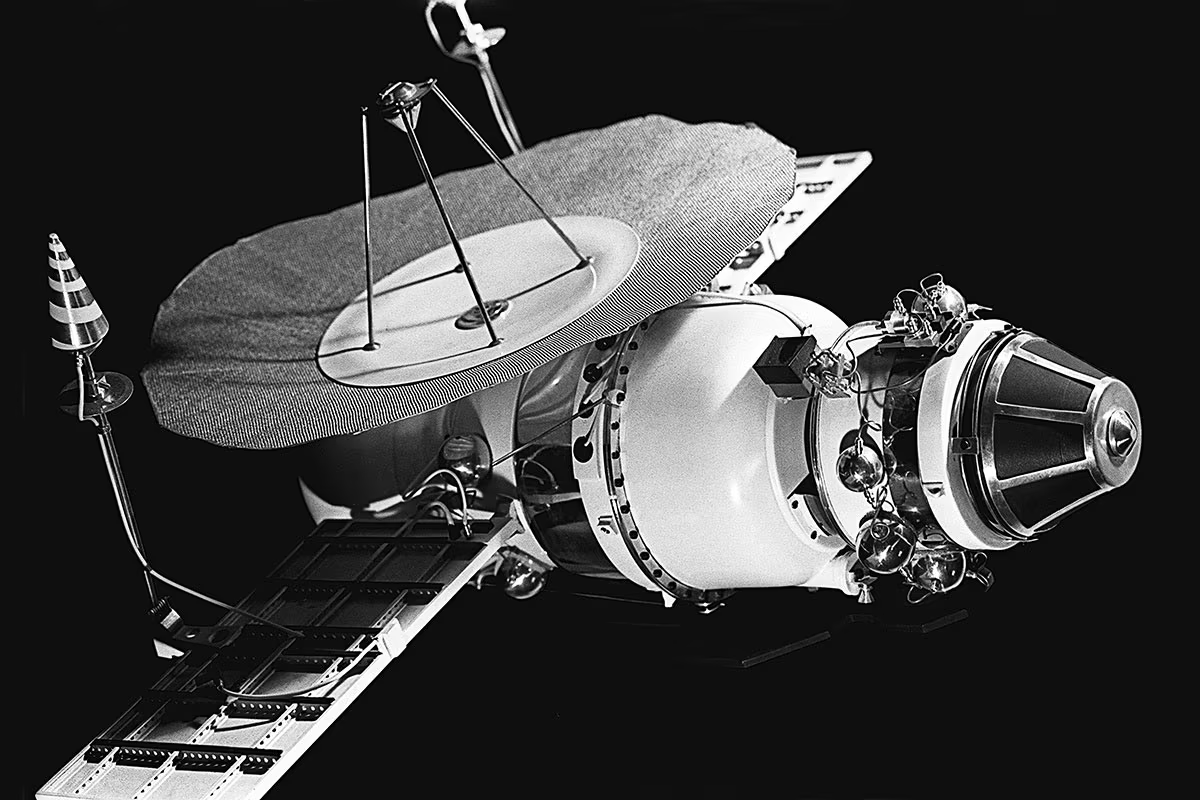

Soviet Spacecraft Falls to Earth Half a Century After Failed Mission to Venus

Uncontrolled Reentry Expected in Coming Days as the Craft Weighs Over Half a Ton