In August 2016, a 70-year-old patient in Nevada died from a bacterial infection that failed to respond to treatment—the pathogen was resistant to all 26 available antibiotics. This rare case served as a stark warning: even "last-resort" antibiotics can no longer guarantee recovery. Over decades, bacteria have perfected their ability to survive the onslaught of drugs. Now scientists warn the world may be entering a new era where routine infections become deadly once more. Already, drug-resistant pathogens kill more than one million people annually—more than HIV/AIDS or malaria.

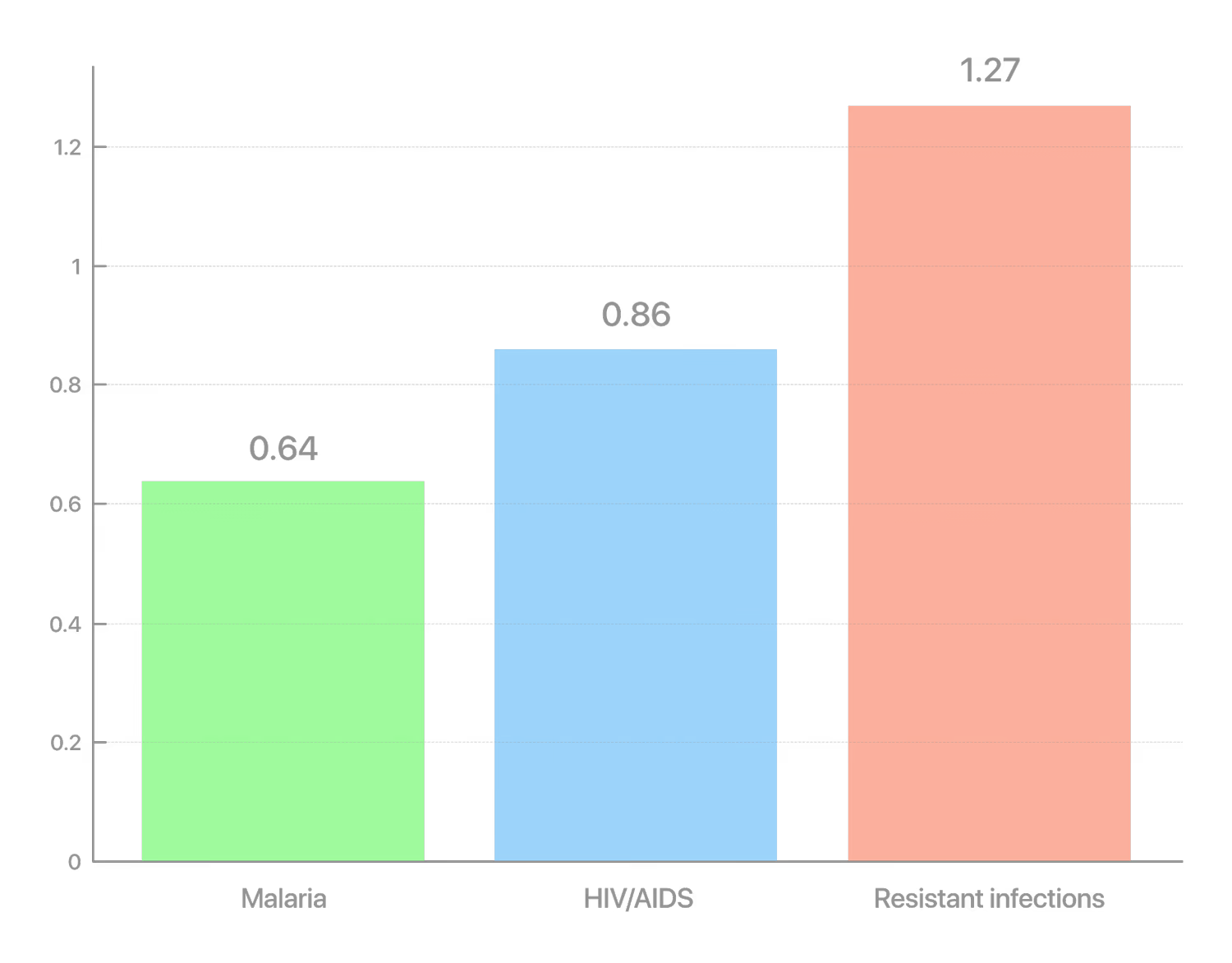

Mortality from infections in 2019, million people

According to a major global study, around 1.27 million deaths in 2019 were directly caused by antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections. By comparison, HIV/AIDS caused 860,000 deaths, and malaria—640,000 in the same year. Thus, antibiotic resistance has already become the leading infectious killer, surpassing more widely known diseases. "Antimicrobial resistance is one of the greatest threats facing the global community. […] We must act urgently," said UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed, commenting on the expert report.

Experts warn that without active measures, the situation will rapidly deteriorate. According to a UN interagency group, by 2050, drug-resistant infections could cause up to 10 million deaths annually—comparable to the toll of the largest epidemics. In practical terms, this means one patient could die every three seconds because antibiotics failed. The World Health Organization classifies antimicrobial resistance as one of the top global threats to health and development. The problem affects all regions and income levels, though the poorest countries are hit hardest.

Resistant bacteria are already complicating the treatment of many diseases. For example, according to global monitoring data, in 2020, roughly one in five cases of common intestinal infections (E. coli in urinary tract infections) did not respond to standard antibiotics. Resistance is also growing among pathogens that cause pneumonia, gonorrhea, intestinal and wound infections. Even tuberculosis—once treatable with basic drugs—has developed strains resistant to frontline medications, killing around 230,000 people a year. As a result, diseases that were recently treatable are once again becoming deadly threats.

Why Is Resistance Rising?

The main driver of the crisis is the misuse and overuse of antibiotics. Doctors often prescribe them without sufficient justification, and patients may take them incorrectly or self-medicate. In some countries, antibiotics are still available without a prescription, leading to uncontrolled use. Agriculture exacerbates the problem: estimates suggest that up to two-thirds of global antibiotic use is in animals—often to promote growth or prevent disease in crowded conditions. This mass "feeding" of bacteria accelerates the emergence of resistant strains that can then spread to humans through food or the environment.

According to WHO and EFSA, traces of antibiotics can remain in meat and milk if proper withdrawal times are not observed. Even low doses may contribute to antibiotic resistance in humans.

In many regions, there is also a lack of sanitation and vaccination. Where infections spread easily, antibiotics are used more frequently—and resistance develops more often. Paradoxically, poor access to medicines in low-income countries also plays a role: when patients can't afford a full course of treatment, incomplete use helps resistant bacteria survive. Ultimately, human activity—from hospital prescriptions to industrial farming—creates ideal conditions for the evolution of "superbugs". The problem is complex, affecting human, animal, and ecosystem health (One Health), and requires an equally comprehensive response.

Medical and Economic Consequences

The rise of resistance undermines the achievements of modern medicine. Procedures once considered routine are becoming risky. Surgeries, joint replacements, cesarean sections, and chemotherapy—all carry the risk of infection, and without reliable antibiotics, doctors hesitate to perform them. "We are at a critical juncture in the fight to safeguard our essential medicines," said WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus. If effective antibiotics are unavailable, even a small wound or a sore throat could become life-threatening—as was the case before the discovery of penicillin.

Beyond the direct threat to health and life, antimicrobial resistance brings massive economic costs. Resistant infections require more expensive treatments and longer hospital stays, taking patients—and their caregivers—out of the workforce. According to World Bank estimates, by 2030 global GDP could shrink by $1 to $3.4 trillion annually due to the spread of resistant pathogens. Healthcare systems may face over $1 trillion in additional costs by 2050. Inaction thus threatens not only public health but also economic stability—on a scale comparable to the 2008–2009 global financial crisis.

In Search of New Solutions

The growing resistance of microbes contrasts sharply with the shortage of new antibiotics. Over the past decades, pharmaceutical companies have significantly reduced research in this field—it is expensive, complex, and yields little profit. Since 2017, only 13 new antibiotics have been approved globally, and only 2 belong to entirely new classes of drugs. Finding an effective molecule is not enough—years of development must also pay off. Yet new antibiotics are typically reserved as a last line of defense and used sparingly, so sales remain low. In 2019, American startup Achaogen went bankrupt less than a year after launching a promising drug against resistant infections. This case exposed a market imbalance: even life-saving medicines do not guarantee survival for the companies that create them. "Antimicrobial resistance is only getting worse, and we are falling behind in developing breakthrough products," admitted Dr. Yukiko Nakatani, WHO Assistant Director-General, pointing to a dire innovation gap. She also noted that many new treatments never reach the patients who need them most.

Nevertheless, scientists are exploring alternatives and ways out of the crisis. Bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—are experiencing renewed interest as a potential weapon against superbugs. Other unconventional approaches are also under development: immunotherapy, drugs that suppress microbial virulence factors, and probiotic methods to restore healthy microbiota. Vaccines are another focus: for example, widespread pneumococcal vaccination is already reducing the incidence of pneumonia that would otherwise require antibiotics. Countries are beginning to implement incentive programs for antibiotic development: from government grants and partnerships to new payment models where hospitals pay not for the number of doses used but for the availability of effective treatments. These measures aim to revive pharmaceutical industry interest and ensure access to new antibiotics for those in need.

Experts agree that fighting resistance requires simultaneous action on several fronts:

Use antibiotics wisely. Limit unjustified prescriptions in medicine and veterinary practice, ban the use of critical human antibiotics for livestock growth promotion, and improve controls over prescription drug sales.

Prevent infections to reduce the need for antibiotics. This includes vaccination, sanitation, hospital hygiene, water purification, and other measures that stop bacteria from spreading.

Invest in the development of new tools. Create conditions (funding, economic incentives, international funds) that encourage pharmaceutical companies to resume the search for antibiotics targeting the most dangerous pathogens. In parallel, new diagnostic tests are needed to quickly identify infections and avoid unnecessary prescriptions.

The global community once won a battle against bacteria with the discovery of antibiotics—but that victory was not final. Today, humanity faces a measured yet urgent challenge: to deploy the full arsenal of science, policy, and common sense in order not to lose the protracted "arms race" between microbes and medicine. Only a balanced approach—from the prudent use of existing drugs to encouraging scientific breakthroughs—will help keep antibiotics effective for generations to come.

Diagnosis and Solutions