Against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s escalating threats of a strike on Iran, a nighttime thunderstorm over Tehran recently jolted some residents awake, sending them rushing from their beds to windows and rooftops—many assumed the long-anticipated confrontation had finally begun.

The alarm proved false. But the sense of an approaching calamity only deepened. On Thursday, the US president warned Iran that it had “at most” 15 days to reach a deal or “bad things will happen.” Washington, meanwhile, has concentrated one of its largest military deployments in the Middle East since the 2003 Iraq war.

Tehran’s residents—many of whom are still reeling from the war with Israel in June and the brutal suppression of anti-government protests last month—fear that a return to violence is only a matter of time.

Across the capital, people speak of sleepless nights. Pharmacists report a surge in demand for sedatives and blood pressure medication. Others are rushing to stockpile supplies—filling carts with rice, beans, and detergents and lining up in long checkout queues.

“I will stay in Tehran,” said Homayoun, a retired civil servant who, like other interviewees, used a pseudonym for safety. He said he was too exhausted to flee the city. “Either the Islamic Republic will kill me or the United States will, but I’m not going anywhere. In this country, it seems impossible even to die a natural death.”

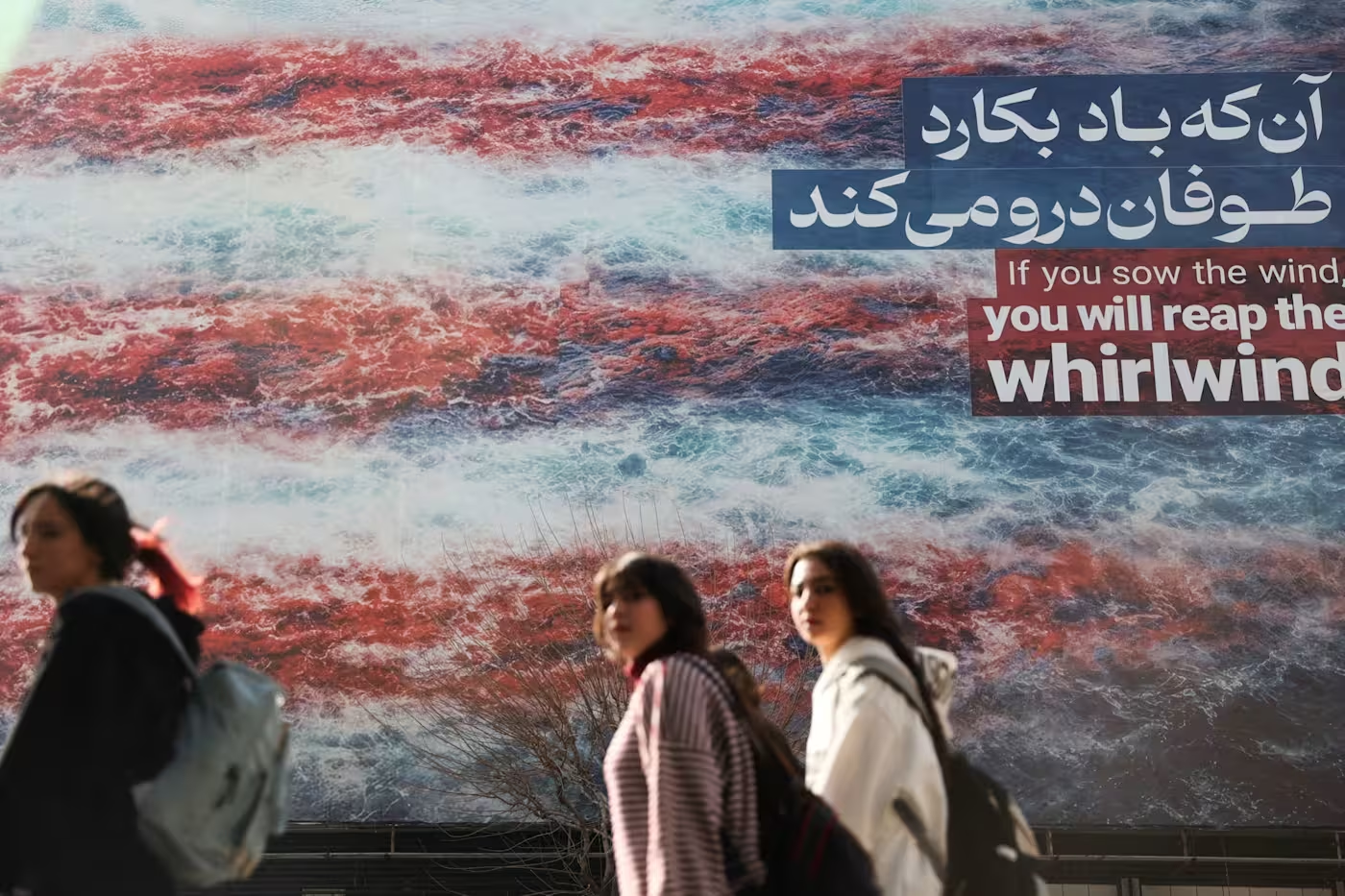

Women in Tehran walk past a billboard bearing an anti-American slogan in Persian and English.

February 2025.

Even before the storm, tension in the city was stretched to the limit. During last week’s celebrations marking the anniversary of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, regime supporters patrolled neighborhoods, chanted slogans, and set off fireworks late into the night. For many who were already bracing for the worst, the scenes were unsettling.

“When they came down our street, I thought the United States had begun an attack,” said Soheila, a woman in her early sixties who lives in an upper-middle-class area of Tehran. She said she assumed people were running out of their homes because of a strike. “Since that night, my blood pressure has gone up. Doctors say it’s stress caused by fear of war.”

In June, when Israel struck Iran, triggering a 12-day war and intense bombardment of Tehran, a wave of nationalism swept the country. Many Iranians rallied around the flag and ignored Israel’s calls to rise up against the theocracy, despite deep frustration with their own leaders.

Now, after the brutal crackdown on anti-government protests last month, the emotional climate has become far more conflicted.

This week, a wave of mourning ceremonies swept the country, marking 40 days—an important date in Iranian cultural tradition—since the deaths of protest participants. The events were the deadliest episode in Iran since the revolution.

The human rights group HRANA said it has confirmed more than 7,000 deaths and continues to verify additional cases. Many Iranians place primary responsibility for the violence on the security forces, while authorities blame armed provocateurs backed by foreign states and cite a far lower figure—3,117 dead.

On February 19, US President Donald Trump warned Iran that it had “at most” 15 days to strike a deal or “bad things would happen.”

The administration of President Masoud Pezeshkian sought to contain public anger after the crackdown—promising pay rises for civil servants and repeatedly offering condolences to the families of the dead. For the first time since the unrest began, even the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said this month that he mourned the deaths of innocent people.

For many Iranians, however, such gestures have failed to persuade. A growing number believe the rift between the state and society can no longer be repaired.

“It fills me with rage and a desire for revenge,” said Mojgan, a teacher in her early forties, describing how she watched videos of the recent mourning ceremonies. “It reminds me of my divorce from my ex-husband. I just wanted him gone—regardless of the consequences. I want the Islamic Republic to disappear, and I don’t care what replaces it.”

Some Iranians fear that publicly criticizing US threats against Iran over the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program could be interpreted by the authorities as support for the theocracy itself and its policies. Others are beginning to see war as a possible way out of the current impasse.

Nasrin, an employee at a private company who took part in the protests, said that “for decades we have been choosing between bad and worse.” “Now I want the country to move in one direction.”

All of this has created an oppressive atmosphere—despite the start of Ramadan, the holy month for Muslims, and the approach of Nowruz, the Persian New Year, next month.

With the start of Ramadan and the upcoming celebration of Nowruz next month, shoppers would normally pour into the streets in large numbers.

Merchants, whose shops at this time of year are usually packed with customers preparing for festive meals and celebrations, speak of an almost complete standstill.

“By now I would have restocked, and people would be buying food for the holidays,” said the owner of a grocery shop in central Tehran. “This year, no one has done so. We simply won’t survive like this.”

Mehdi, a construction contractor, says he has been unable to carry on with normal life. “We are trapped between a regime that is unwilling to give ground and the United States and Israel, which are also not prepared to back down,” he said. “With this level of uncertainty, it’s impossible to live.”