The time teenagers spend on social media has more than doubled over the past decade and a half, now averaging around three hours a day. According to the World Health Organization, in 2022 more than one in ten adolescents showed signs of problematic or even addictive behavior—ranging from an inability to control use to symptoms of “withdrawal” when offline.

“Everyone understands it’s addictive,” says Polish high school student Hanna Kuzmitowicz, who worked with Poland’s EU presidency on the issue. “I know the dangers and the benefits. But I still keep using it.”

Alarmed by health experts, European governments are seeking ways to curb young people’s access to phones. Options under consideration include awareness campaigns, age verification systems and outright bans. Each country has the freedom to choose its own path, and many are exercising it. French President Emmanuel Macron has proposed a blanket ban on social media use by children under 15. Denmark, Greece, Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and several others are also debating tougher restrictions.

Tech companies, for their part, are introducing their own measures: restricting content by age, disabling certain features and adding extra privacy settings. Critics, however, argue these steps are insufficient, and there is still no clear sense of which approach will prove effective.

Scientists Disagree on Social Media’s Effects, but Evidence of Harm Is Mounting

Some researchers stress that social media should not be viewed solely in negative terms—it can also bring benefits. “Certain technologies genuinely help teenagers strengthen their friendships,” says Jessica Piotrowski, head of the School of Communication Research at the University of Amsterdam and a consultant to YouTube on child protection. A number of studies back this conclusion.

Yet growing evidence points the other way: declining overall well-being, rising rates of depression, disrupted sleep and a greater propensity for substance use. “Regulation and some form of accountability for the harm caused to children and adolescents are essential,” says Kadri Soova, director of the organisation Mental Health Europe. In her view, it is not only dialogue with industry that matters, but also clear rules: “If self-regulation is absent or superficial, laws must apply.”

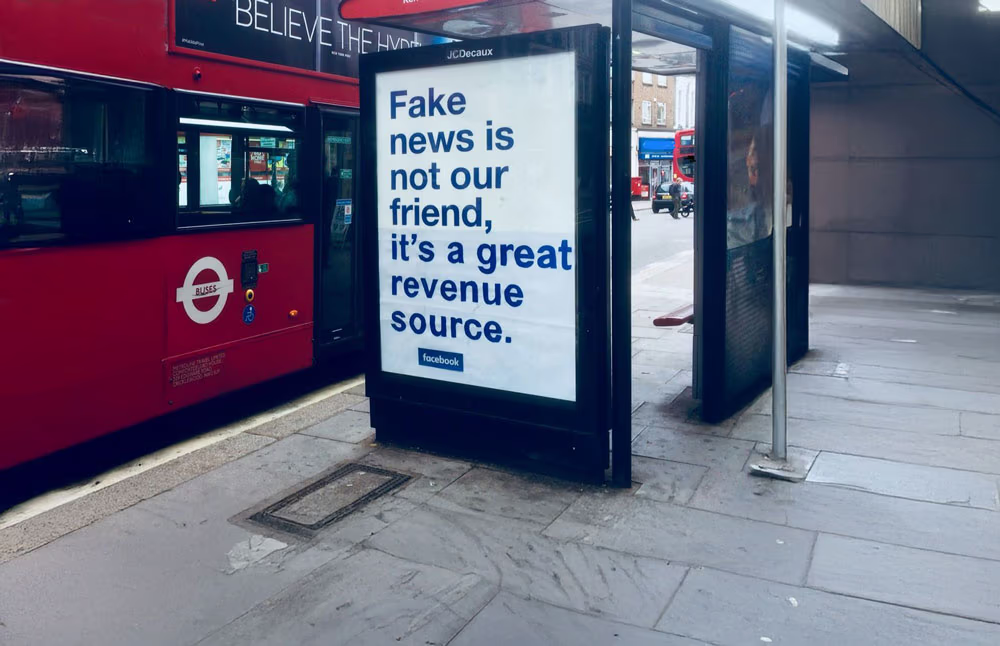

A series of scandals in recent years has shown that companies do not always put the safety of minors first. In 2021, former Meta employee Frances Haugen released internal documents showing that executives were aware of the harm to teenagers’ mental health but failed to act. Public health experts argue that existing regulatory tools are insufficient. According to them, platforms are deliberately designed to foster dependency.

Endless Scroll

How Social Media Becomes a Trap for Attention and a Source of Anxiety

"I Have to Fix This"

Jony Ive on Why His New Device Must Not Repeat the Fate of the iPhone

Neuropsychiatrist Theo Compernolle, former professor at the Free University of Amsterdam, argues that regulators must focus squarely on the companies: “Otherwise it is like fighting drugs while ignoring the producers.” A similar point is made by Mark Petticrew, professor of public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, who says the social media industry, like alcohol, tobacco or gambling, is built on denying the harm it causes.

In June, EU health ministers adopted Council conclusions calling on governments to develop preventive measures. Ideas included creating screen-free zones and limiting digital time in schools, as well as placing greater responsibility on digital platform designers.

EU Tightens the Rules: The Digital Services Act and New Requirements for Platforms

One of the EU’s key documents regulating the work of digital platforms is the Digital Services Act (DSA). It requires social networks to introduce “proportionate and adequate measures to ensure a high level of privacy, security and protection for minors.”

Meta (Facebook and Instagram), as well as TikTok, have already become the subject of investigations over suspected breaches of these rules. Yet in its final form the law left its provisions too vague, forcing the European Commission to draft a set of contentious recommendations clarifying what platforms are expected to do.

Among them are bans on using minors’ browsing history to recommend content, disabling features such as “streaks” and read receipts, setting privacy and safety controls by default, and the option to restrict access to certain functions, including the camera.

These recommendations are non-binding. Moreover, if a teenager enters a false age or parents bypass built-in filters, the measures lose their effectiveness. As a result, increasing attention in the debate is focused on one issue: how platforms can realistically verify the age of their users.

Regulators Push for Age Verification, Companies Shift the Responsibility

Under the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), children under 13 cannot give consent for their personal data to be processed in online services. TikTok and Instagram formally allow access only from the age of 13, but regulators have long known that a simple tick-box does not work. According to the Danish nonprofit Børns Vilkår, cited in a government study, 94% of children in Denmark open accounts before turning 13.

That is why the regulatory debate is increasingly shifting toward mandatory age verification—without it, other measures are meaningless. The dispute centers on who should bear responsibility. Critics argue it should fall on the social networks themselves, while Meta and TikTok point to Google and Apple, the developers of mobile operating systems, which they say should be responsible for built-in verification mechanisms.

Meta’s director of government affairs, Helen Charles, said that new laws should mandate age checks and parental consent at the operating system and app store level. Such an approach, she argued, “will be easier for parents” while also ensuring privacy protection.

Google and Apple, however, insist on shared responsibility. “We believe this is a collective task… There is no single universal solution that one company could implement for everyone,” said Vinay Goel, Google’s director of age assurance. In his view, app developers are best placed to understand the risks posed by their products.

Bans in Question: Ministers and Teenagers Doubt Their Effectiveness

Even among advocates of tough regulation—including teenagers themselves—there is skepticism that an outright ban would achieve the desired results. Natasha Azzopardi-Muscat, director of the WHO’s Division of Country Health Policies and Systems, argued that “strict enforcement of age checks, parental tools and digital literacy programmes” could prove more effective.

Teenagers share these doubts. Hanna Kuzmitowicz points out that there will always be ways to bypass bans and restrictions, which makes them of limited use.

Health ministers generally agree that there is not yet enough evidence to justify a blanket ban. “How could it realistically be enforced?” asked Cyprus’s health minister Michalis Damianou, stressing that what matters more is ensuring that any measures introduced actually work in practice.

Malta’s health minister Jo Etienne Abela added: “A ban on social media is a step into the unknown. Such a policy has no evidence base. But on the other hand, we all know the problem exists. Should the absence of evidence paralyse us and prevent action?”