Since returning to power in August 2021, the Taliban have systematically dismantled the fundamental rights and freedoms of women in Afghanistan. Bans on education, employment, and unaccompanied travel have become pillars of state policy, formally justified under Sharia law. Now, for the first time in its history, the International Criminal Court is considering arrest warrants against Taliban leaders—on charges of systematic gender persecution, treated as crimes against humanity.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) is, for the first time, weighing the issuance of arrest warrants for crimes against humanity related to gender-based persecution of women. The potential defendants include Taliban supreme leader Haibatullah Akhundzada and the group’s chief justice Abdul Hakim Haqqani. ICC judges stated that they have "reasonable grounds" to believe that from August 2021 at least through January 2025, the two men were responsible for a policy of "systematic deprivation of women and girls of their fundamental rights and freedoms" in Afghanistan. This includes, in particular, the right to education, freedom of movement, expression, thought, conscience, and religion.

The Taliban’s reaction was predictable. Spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid dismissed the accusations as "nonsense," asserting that Afghanistan’s government does not recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction. He further emphasized that an Islamic state must "fully implement Sharia," including dress codes, male guardianship, and gender segregation in education and employment.

In practice, this policy has taken forms that human rights groups and international organizations have documented in detail. Women are forbidden from working without a husband or a close male relative. In one reported case, officials from the religious police told a woman she had to marry if she wished to keep her job at a medical facility, arguing that working without a husband was "improper." Since December, in the province of Paktia, women without a mahram have been banned from entering hospitals. Staff from the Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice inspect medical centers to ensure compliance. Similar enforcement occurs at universities, offices, and in public spaces: women are stopped at checkpoints and detained for violations, including failure to follow the dress code. In 2022, a decree was issued mandating that women cover their faces and wear the burqa—a return to the rules imposed during the Taliban’s previous rule in the 1990s.

Rights That Still Need Defending

Support for Abortion Rights Is Declining Among Men

Women Have Become More Vocal Since the Repeal of Roe v. Wade

Trump Revokes Emergency Abortion Protections in Hospitals. The Rule Had Required Doctors to Save Women With Life-Threatening Complications

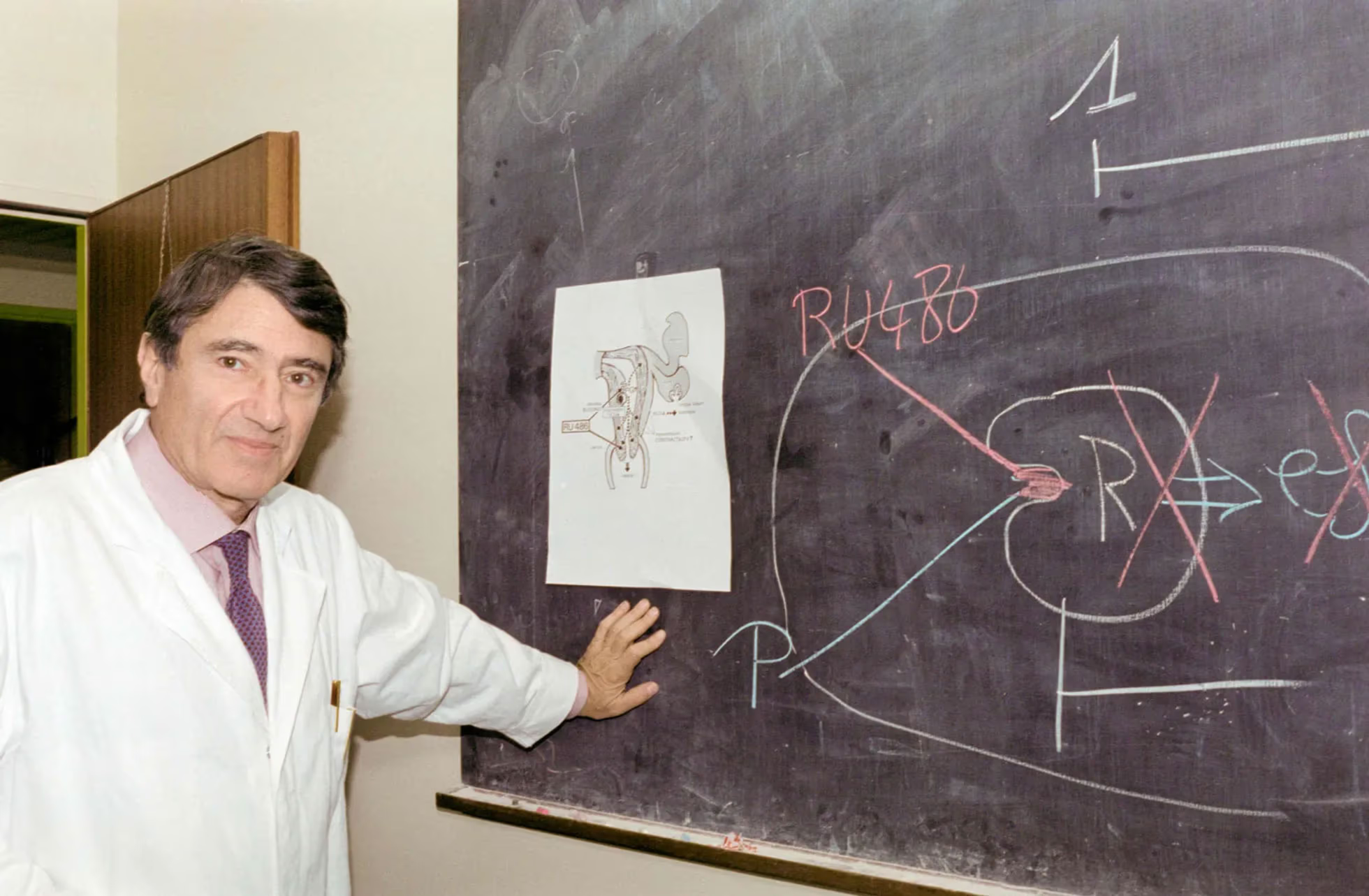

The Scientist Who Gave Women the Right to Choose

The Story of Étienne-Émile Baulieu—A Man Who Changed Reproductive Medicine and Stayed True to Himself

A particular focus of Taliban policy has been women who exhibit independence. In October 2023, three female hospital workers were detained on their way to work—unaccompanied by a male guardian. They were released only after their relatives signed written pledges that it would not happen again. Women have also been arrested for purchasing contraceptives, even though such products are not officially banned. According to the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), women without a mahram are especially vulnerable, subject to unwritten but strictly enforced restrictions.

Nevertheless, even if ICC judges approve the warrants, the actual arrest of Taliban leaders remains highly unlikely. The Hague-based court has no enforcement powers of its own and relies on member states to detain and extradite suspects. Afghanistan is not among them. In practice, such warrants constrain international movement: individuals named in them risk arrest in countries that recognize the ICC’s jurisdiction. But in the case of Akhundzada and Haqqani, even that seems hypothetical—there is little indication they intend to leave the country.