On Sunday, October 5, Syria is holding parliamentary elections—the first since longtime autocrat Bashar al-Assad was overthrown in December following a rebel offensive.

For nearly half a century under the Assad family, elections were held regularly and were, in theory, open to all citizens. In practice, the Baath Party maintained full control of parliament, and voting itself was widely seen as a formality.

Analysts note that during those years, the only genuine competition took place before election day—within the Baath Party itself, where members fought for a place on candidate lists.

Still, the current vote can hardly be described as fully democratic. Most seats in the People's Council are being allocated by electoral colleges in each district, while roughly one-third will be appointed by the interim president, Ahmad al-Sharaa.

Although there will be no direct popular vote, the results will serve as an indicator of how serious the interim authorities are about ensuring political inclusivity—above all, the participation of women and minority groups.

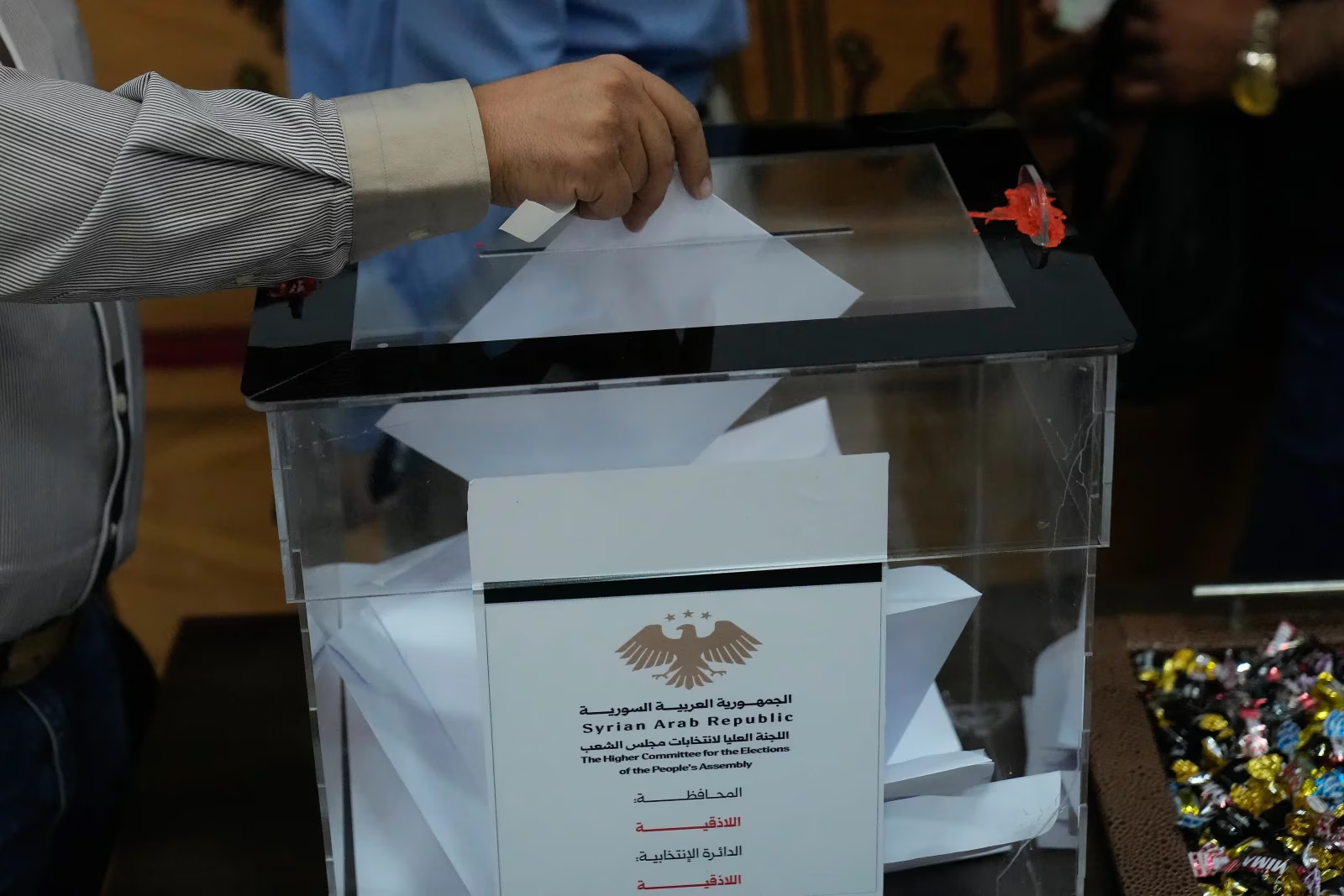

A member of Syria’s electoral college casts a ballot during parliamentary elections at a polling station in Latakia, a coastal city in Syria, on October 5, 2025.

How the New Elections Work and Who Chooses the Parliament

The People’s Council of Syria is made up of 210 members, two-thirds of whom will be elected on Sunday, while the remaining third will be appointed. The elected seats are distributed among constituencies in proportion to their population, with voting conducted by electoral colleges in each district.

In theory, about 7,000 members of the electoral colleges from 60 districts—formed from local nominees by special commissions—are expected to elect 140 representatives.

However, voting in the province of Sweida and in the northeastern areas controlled by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces has been postponed indefinitely due to tensions between local administrations and the central government in Damascus. Those seats will remain vacant.

As a result, in practice, around 6,000 members of the electoral colleges will cast their votes in roughly 50 districts to choose 120 deputies.

The largest district is the one that includes the city of Aleppo, where 700 college members will elect 14 deputies. In Damascus, 500 voters will allocate 10 seats. All candidates are nominated from among the members of the colleges themselves.

After Assad’s ouster, the interim authorities dissolved all existing political parties—most of which had been closely tied to the former regime—and have yet to establish a mechanism for registering new ones. As a result, all candidates are running as independents.

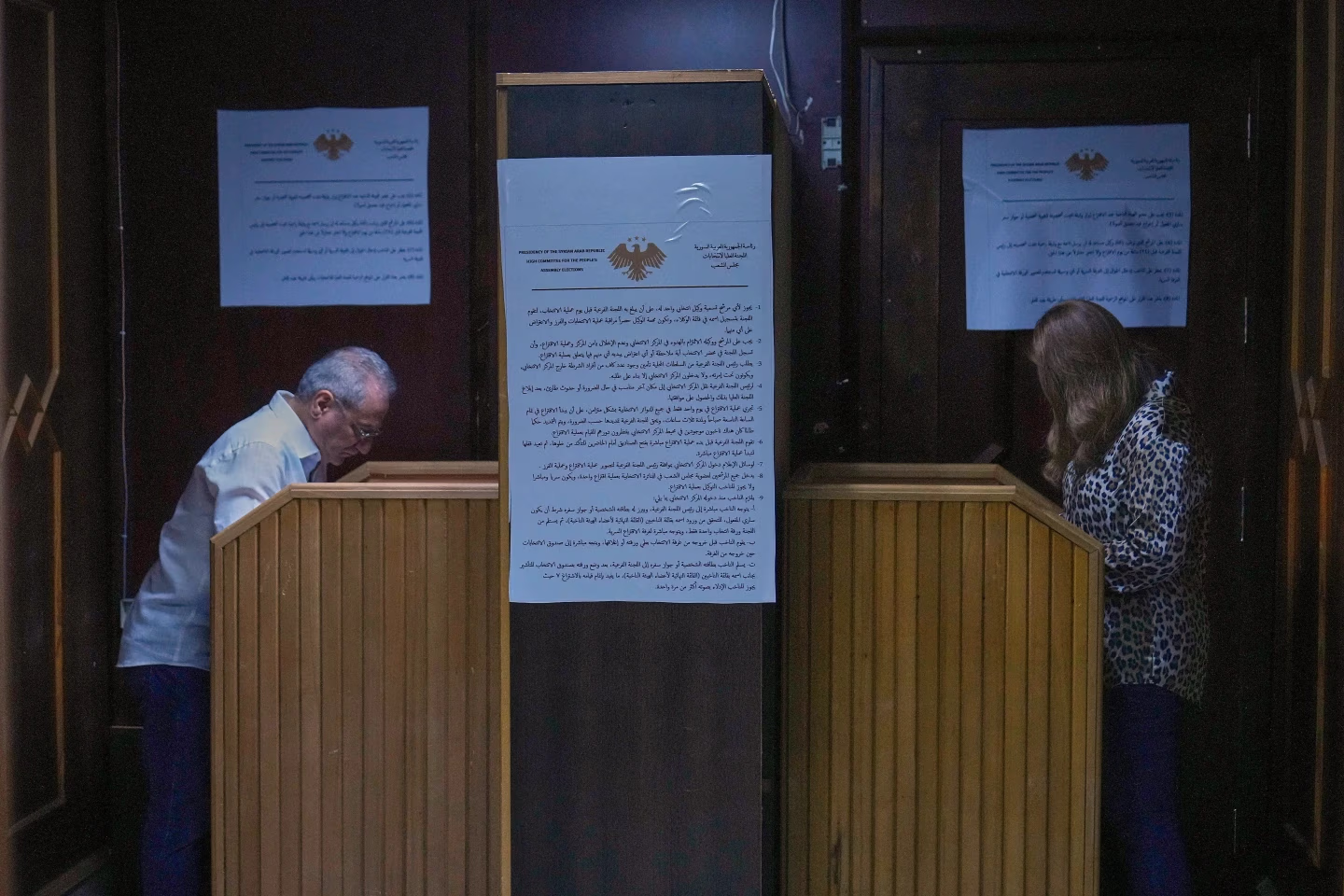

A member of Syria’s electoral college casts a ballot during parliamentary elections at the governor’s polling station in Latakia, a coastal city in Syria, on October 5, 2025.

Why the Authorities Abandoned a Nationwide Vote

The interim authorities argue that holding a nationwide vote is currently impossible: after nearly 14 years of civil war, millions of Syrians have been displaced within the country or forced to flee abroad, and many have lost personal identification documents—making it unrealistic to compile accurate voter rolls.

The new parliament’s term will last 30 months. During that time, the government is expected to prepare the conditions necessary for holding nationwide elections.

The absence of a popular vote has drawn criticism as undemocratic, though some analysts consider the authorities’ arguments justified.

“We don’t even know how many Syrians are currently in Syria,” says Benjamin Feve, senior analyst at Karam Shaar Advisory, pointing to the scale of both internal and external displacement. According to him, “under the current circumstances, it is extremely difficult to compile voter lists or organize participation of Syrians from the diaspora in elections where they reside.”

Haid Haid, senior fellow at the Arab Reform Initiative and Chatham House, notes that a far greater concern lies in the lack of transparency surrounding the selection criteria for electors.

“Especially when it comes to forming subcommittees and colleges, there is no oversight whatsoever, leaving the entire process potentially open to manipulation,” he says. According to him, frustration grew after electoral bodies “removed the names of certain candidates from the initial lists without providing any explanation.”

A member of Syria’s electoral college fills out a ballot in the voting booth at the governor’s polling station in Latakia, a coastal city in Syria, on October 5, 2025.

Weak Representation of Women and Minorities Remains a Problem

The parliament has no quotas for women or for religious and ethnic minorities. Although women were required to make up at least 20% of electoral college members, that did not guarantee them proportional representation among candidates or those elected.

According to the state-run SANA news agency, citing the head of the national election commission, Mohammed Taha al-Ahmad, women account for only 14% of the 1,578 candidates who made it to the final lists. In some districts, their share reaches 30–40%, while in others there are no female candidates at all.

The absence of elections in Sweida province, where the majority of the population is Druze, as well as in the Kurdish-controlled areas of the northeast, combined with the lack of quotas for minorities, has raised questions about the representation of communities outside the Sunni Arab majority.

The issue is particularly sensitive after recent outbreaks of sectarian violence in which hundreds of civilians from Alawite and Druze communities were killed, many of them by fighters affiliated with government forces.

Feve notes that the electoral district boundaries were drawn in such a way that in some of them, minorities form the majority.

“If the authorities wanted to limit their influence, they could have merged these districts with regions dominated by Sunnis, effectively ‘diluting’ the minorities—but they did not,” he said.

According to Haid, officials also point to the one-third of parliamentary seats directly appointed by Ahmad al-Sharaa as a tool for “enhancing the inclusivity of the legislative body.” The logic is that if women or minority representatives are underrepresented among those elected by the colleges, the president can offset that imbalance through his appointments.

Nevertheless, the lack of representation from Sweida province and the northeastern regions remains a problem, even if al-Sharaa appoints deputies from those areas.

“In the end, no matter how many people are appointed from these regions, the disagreements between the de facto local authorities and Damascus over their participation in the political process will remain a key source of tension,” he said.