In 1972, the Soviet Union launched the Kosmos-482 spacecraft as part of its Venus exploration program—but a rocket failure left it stranded in Earth’s orbit. Nearly 53 years later, its descent module, designed to withstand extreme conditions, is now headed for an uncontrolled reentry, raising concerns among scientists.

A Soviet-era spacecraft built in the 1970s for a Venus landing is expected to make an uncontrolled reentry into Earth’s atmosphere in the coming days. Space debris experts are unable to predict exactly where the half-ton metal object will land or how much of it will survive reentry.

Dutch satellite tracker Marco Langbroek estimates the reentry will occur around May 10. If the probe remains partially intact, fragments could hit the ground at speeds of up to 240 kilometers per hour.

"There is a degree of risk, but no reason for panic," Langbroek said in an email. He noted that the object is relatively small, and even if it survives atmospheric entry, "the risk is comparable to that of a random meteorite fall—something that happens several times a year. You’re far more likely to be struck by lightning in your lifetime."

Langbroek added that while the odds of the spacecraft causing harm are extremely low, "they can’t be ruled out entirely."

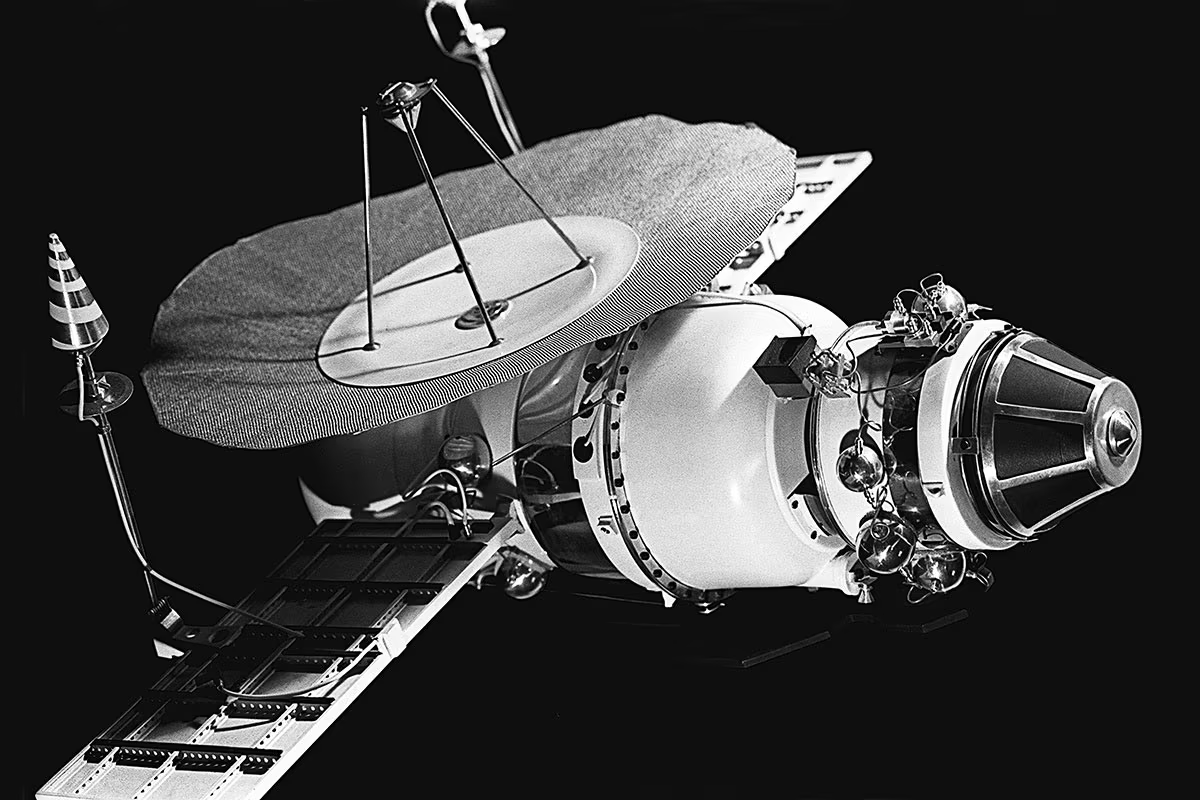

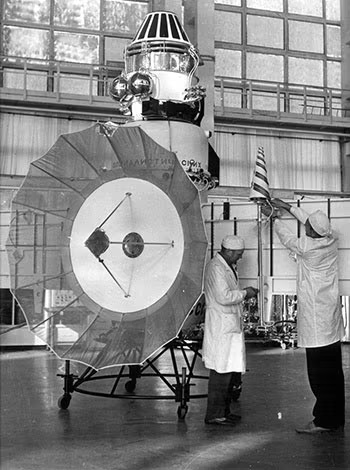

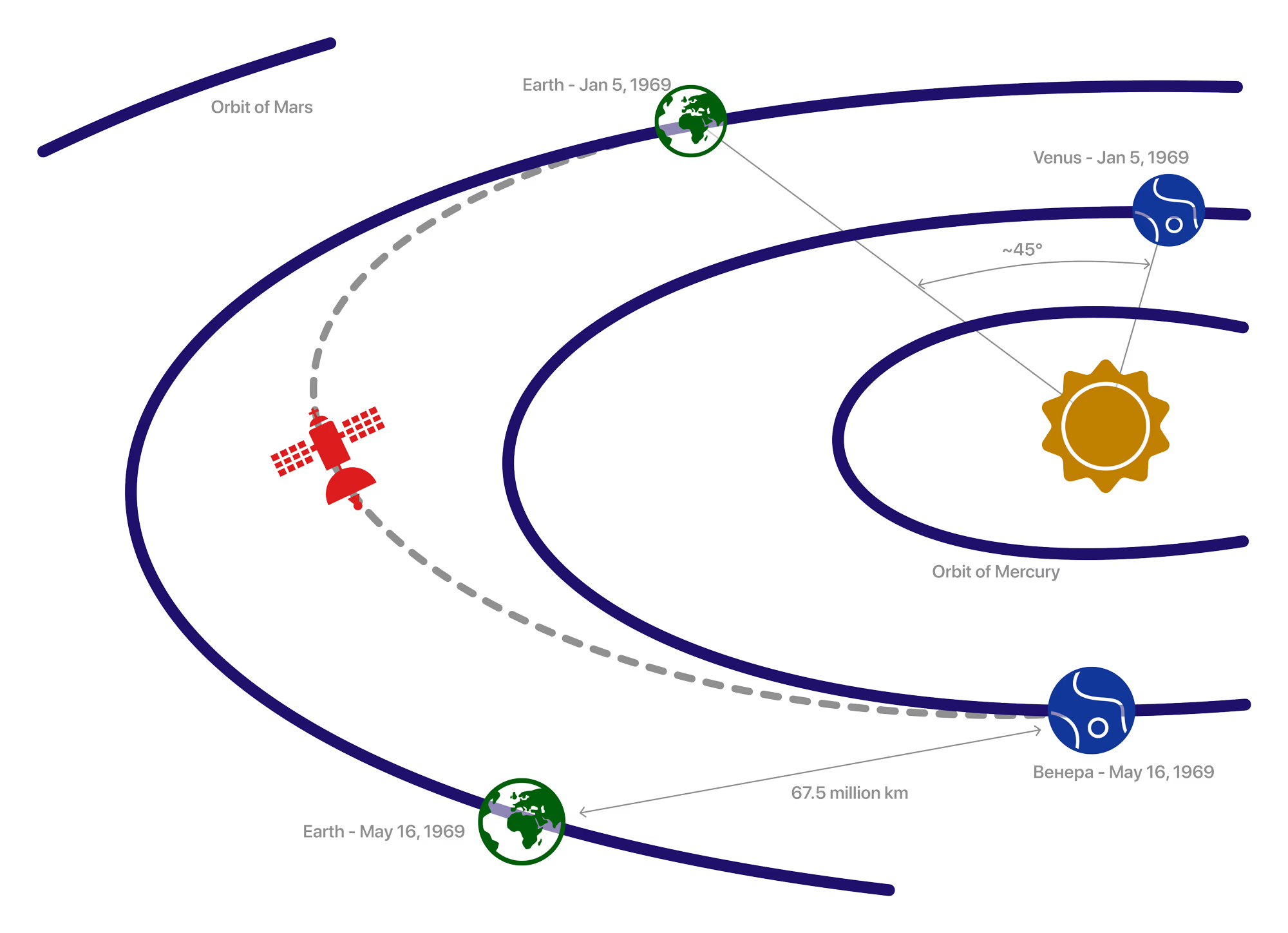

The spacecraft, known as Kosmos 482, was launched by the Soviet Union in 1972 as part of a series of missions to Venus. It was sent into space just four days after its twin, Venera 8, which successfully landed on the planet and transmitted scientific data about its atmosphere. Both missions lifted off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome aboard Molniya rockets and carried identical descent modules. But while Venera 8 completed its mission, Kosmos 482 failed to leave Earth’s orbit due to an upper-stage rocket malfunction.

Flight Diagram of the Kosmos 482 Spacecraft

The main body of the spacecraft reentered Earth's atmosphere within a decade after launch. However, according to Langbroek and other researchers, the descent module—a spherical object about one meter in diameter—continued orbiting Earth on an elongated trajectory for 53 years, gradually losing altitude.

According to Marco Langbroek of Delft University of Technology, there is a significant chance that the over-500-kilogram descent module will survive reentry. It was built to land on Venus—a planet with surface temperatures around 470 °C and pressures exceeding 90 atmospheres. Its hull is made of titanium, and the heat shield consists of multi-layered composites designed to withstand extreme temperatures. Inside were instruments to analyze atmospheric composition, pressure, and temperature.

However, experts doubt that the parachute system—dormant for half a century—will function properly. The heat shield may also have degraded over time.

"It would be better if the heat shield fails, so the craft burns up in the atmosphere," wrote astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in an email. "But if the shield holds, you’re looking at half a ton of metal falling to Earth."

The potential impact zone spans latitudes between 51.7 degrees north and 51.7 degrees south—that is, from London and Edmonton in Canada to Cape Horn in South America. However, since most of Earth’s surface is ocean, the likelihood of the object falling into water is high, Langbroek noted.

Far from Earth

Still Alone in the Universe

Why the SETI Project Hasn’t Found Extraterrestrial Life in 40 Years?

The Milky Way From All Corners of the Earth

Stunning Images From the Annual Capture the Atlas Photo Contest