In August 1965, the arrest of African American Marquette Frye in the Watts neighborhood—accompanied by police use of force—sparked six days of unrest in Los Angeles. Thirty-four people were killed, more than a thousand injured, and damages reached $40 million. The events prompted President Lyndon Johnson to establish the Kerner Commission, which warned that the United States was moving toward “two societies—one Black, one white, separate and unequal.” Today, experts say many of the problems have only deepened, and the commission’s updated report once again calls for decisive action against poverty, racial injustice, and police abuse.

The United States is marking the 60th anniversary of the Los Angeles uprising—a precursor to the wave of urban protests and unrest of the late 1960s and 1970s. The anniversary is accompanied by renewed calls to return to the anti-poverty measures outlined in the Kerner Commission’s landmark 1968 report.

The updated report—titled "Creating Justice in a Multiracial Democracy: The Kerner Commission Updated"—includes recommendations to reduce inequality, racial injustice, and child poverty, which remain acute problems today. Many of the original proposals were never implemented, but activists hope for change amid the growing ranks of progressive candidates running in elections across multiple states.

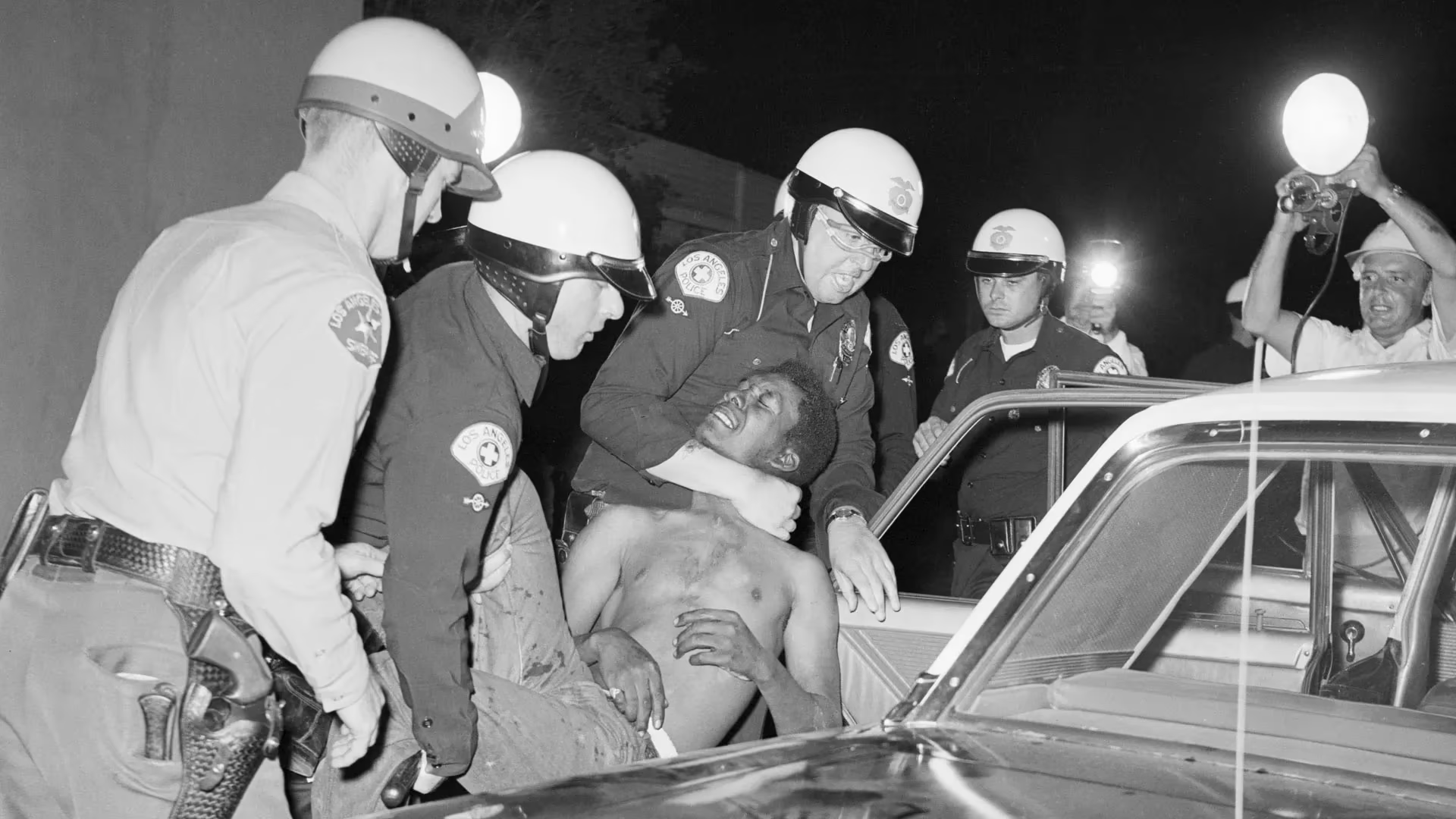

The unrest that erupted in the Watts neighborhood on August 11, 1965, was sparked by the arrest of 21-year-old African American Marquette Frye on suspicion of drunk driving. Witnesses said police used force against him, his brother, and their mother. Six days of clashes and arson left 34 people dead, more than 1,000 injured, and about 4,000 arrested. Damage was estimated at $40 million, and 14,000 National Guard troops were deployed to the area.

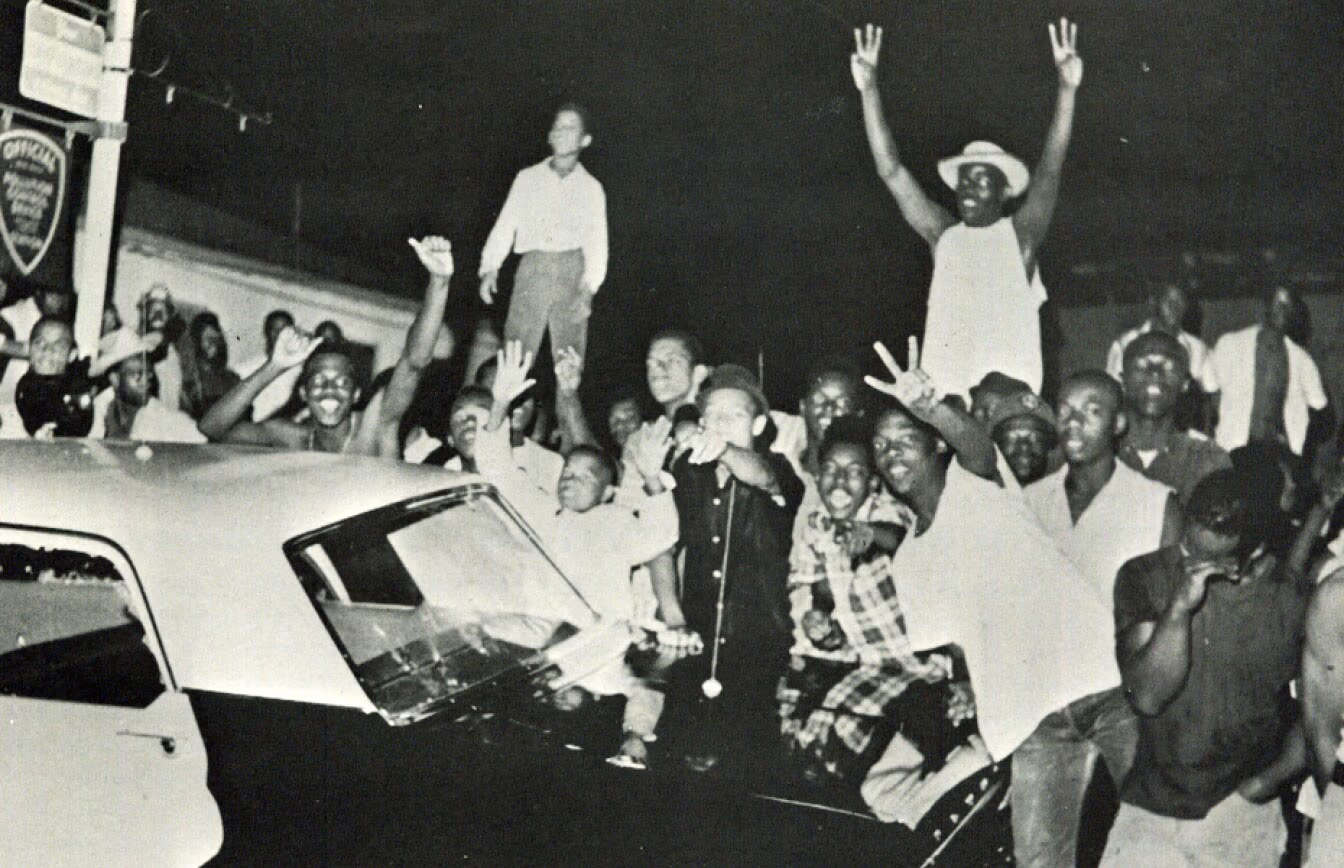

Residents of the neighborhood during the unrest. August 1965.

National Guard troops and barricades. August 1965.

The events convinced Martin Luther King Jr. to broaden the civil rights agenda to include economic inequality and the challenges facing cities in the North and West. In the years that followed, outbreaks of violence swept through Detroit, Chicago, Washington, Newark, and hundreds of other cities—driven by racial discrimination, unemployment, and police abuse.

According to Alan Curtis, president of the Eisenhower Foundation and editor of the updated report, the underlying causes of the protests of the time have not disappeared—and in some respects, conditions have worsened. He called for pragmatic, evidence-based policies to address child poverty and police misconduct, as well as an end to ideological polarization. Among the proposals were need-based school funding, a federal police reform, greater minority representation in the media, and a requirement to address poverty issues during election campaigns.

The last surviving member of the Kerner Commission, former senator Fred Harris, noted as recently as last year that poverty rates in the United States are higher than in 1968, and that “it is harder to escape it today.” Census data show that in 2023, 36.8 million Americans (11.1% of the population) lived in poverty, including about 20% of Latinos and 17% of Black Americans.

Martin Luther King Jr. addresses residents of Watts, declaring: “I am here to support you because you supported me in the South.” He spoke just a few blocks from the areas most devastated during nearly a week of unrest. August 18, 1965.

A National Guard jeep patrols the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles after six days of unrest. August 18, 1965.

Marc Morial, president of the National Urban League, described the past six decades as “a mix of progress and setbacks,” with most of the negative shifts occurring in the last decade. Representatives of Color Of Change PAC and the League warn of “a systemic campaign” to roll back civil rights protections, diversity initiatives, and the political influence of Black Americans.

The Kerner Commission was established by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967 amid unrest in Detroit that claimed 43 lives. Its members—governors, mayors, and senators from both parties—traveled across cities and heard Black residents voice grievances over job scarcity and poor relations with the police. The final report delivered a landmark warning: the nation was “moving toward two societies, one Black, one white—separate and unequal.”