The New York Times tells the story of 25-year-old Serhiy Hrebinik, a marine of the 36th Brigade who was captured during the defense of Mariupol in April 2022. After 1,157 days he returned home—and is still not ready to tell his mother about the torture.

First came the journey back. After the exchange—a brief interrogation by security services, followed by rehabilitation in a Kyiv sanatorium. Psychologists asked about captivity and offered familiar advice: don’t be alarmed if emotions begin to shift. "At first I didn’t notice anything unusual, but later I realized I was having memory problems," he said. "Still, I hope it will get better." That summer, still on active duty, Serhiy boarded a bus and went home to Trostianets for thirty days. The return was quiet: in June there was no welcome at the station, his family learned of his release only the day he crossed the border.

While Decisions Are Made Above

"You Were Born in Captivity, You Live in Captivity"

The Story of a Ukrainian Marine Who Returned From Hell

"Everything Will Be Fine."

How Ukrainian Prisoners Die in Russian Prisons—and Why Kyiv Sees It as Evidence of War Crimes

Home had changed too. In the kitchen, where tea, talk, and ordinary light once lingered, silence now often prevails. "We imagined we would sit at the table and talk for hours when he came back," says his sister Anna. "But it turned out differently." She remembers the past: "He was very cheerful, smiling, open." Now he is "sociable, but often drifts into his thoughts, sometimes sad. You look at him and ask: 'Serhiy, why are you so downcast?' And he replies: 'Just thinking.'" In those moments, Anna adds, her brother "is not with us."

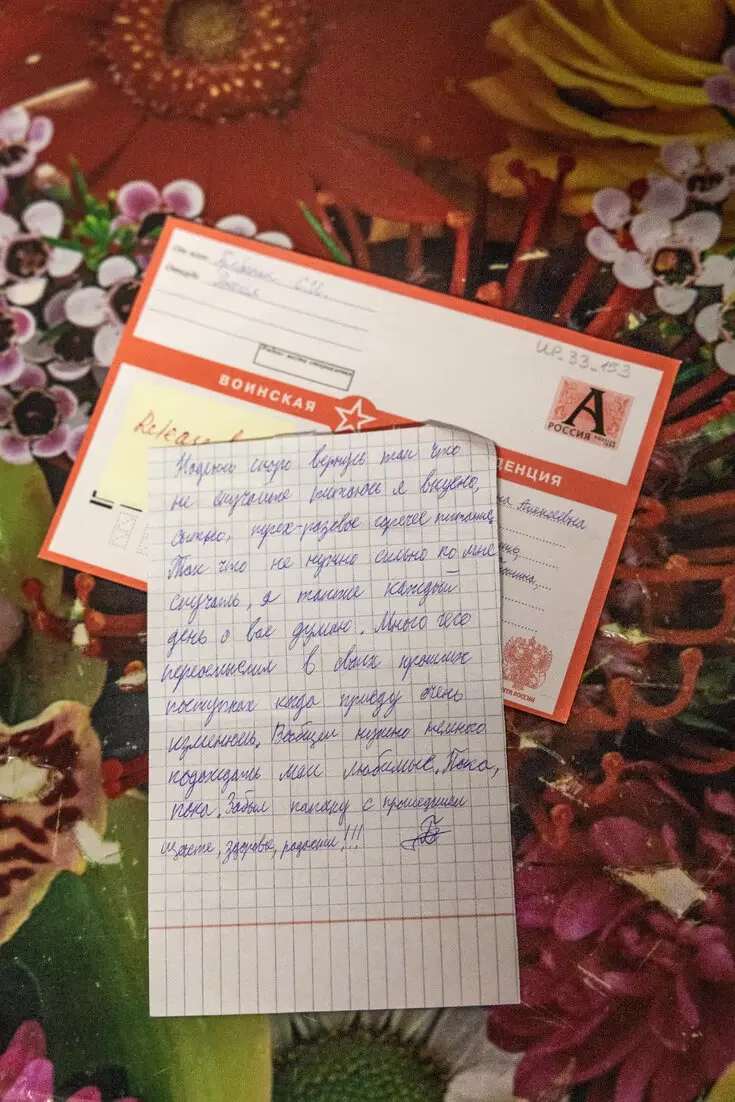

A letter Serhiy Hrebinik sent to his family while in captivity.

From Trostianets to the prison door—three years and a little more. In Mariupol he served as a mechanic in the 36th Brigade: the city was already encircled, a breakout attempt failed, and on April 12, 2022 they were captured. What followed were transfers, convoys, cells, routines. He was beaten almost daily, deprived of sleep, poorly fed. When a guard struck his head, his ear was deformed and the wound became infected. "I tried not to lose hope, telling myself: fine, this month they’ll let me go. If not, I shifted the hope to the next," he recalls. The only respite came from rare access to books—he devoured whatever volumes he could find. Sometimes guards organized chess or football: winners earned extra rations. The main event was the arrival of new prisoners: "The information they brought was like live television: 'Tell us, what’s happening in Ukraine? What’s the news?'"

Mariupol became a key strategic target for Russian forces, securing a land corridor between occupied Crimea and eastern Ukraine. April 2022.

The heavily damaged railway station in Trostianets, Ukraine—Serhiy Hrebinik’s hometown. April 2022.

Behind the barbed wire he tried to hold on to home. Once, a soldier who had passed through Trostianets before being captured was placed in his cell—"he said everything was fine." Serhiy admitted his greatest fear was that his father would decide to take revenge and go to the front. His mother, Svitlana, works at the railway station, his father, Ihor, delivers mail; the road often leads close to the border and beyond, to the front line. The town has changed over these years: burned-out apartment blocks were repainted, repairs began on the station roundabout, and nights became more uneasy—Russian drones increasingly appeared over the rooftops, sometimes crashing and exploding in the streets.

The day of release felt strangely hollow. In Chernihiv, near the border, his gaze met that of other relatives of prisoners. They showed photographs and asked if he had seen their loved ones. "They all looked at me with hope," Serhiy says. That feeling—the burden of return—stayed with him at home too: why was it he who came back, and not those whose names he never learned.

Ihor, Serhiy Hrebinik’s father, at home in Trostianets last year, while his son was still held in Russian captivity.

Families and friends of missing Ukrainian soldiers in Chernihiv on the day of Serhiy Hrebinik’s release.

Now he is learning again to live at the pace of ordinary days. Morning workouts in the school gym, the occasional fishing trip with those still around, a nephew in the house where the smell of fresh paint lingers after renovations. The slam of a door makes him flinch—the body remembers faster than the mind. His dreams are not of torture but of the battles for Mariupol; he speaks little of captivity—and seems to either not remember or not want to recall much of it. "I blame myself and our army for the failure of that breakout," he admits. What comes next is unclear: he may return to service, or he may take advantage of the right granted to former prisoners of war to leave the country.

Serhiy Hrebinik at home in Trostianets this month.

His mother knows only a fraction. He told her about one memory he often returned to in his cell. "He told me he could see a river from the window," says Svitlana. "He said: 'I looked at the night sky, and there were almost no stars. And I thought how beautiful Trostianets is, where the whole sky is filled with stars.'" For now, that is enough. The rest will come later, when memory steadies and words find their way.