In 2025, humanity once again showed only marginal progress in confronting the climate crisis. Nature’s response was predictable—oceans and seas continue to reclaim coastal land from human settlement.

Rising global sea levels and accelerating coastal erosion are leading to the loss of tens of thousands of square kilometers of land. This is a global process: nearly a third of the Earth’s ice-free coastline consists of sandy shores, which are among the most vulnerable to destruction.

The consequences are already extending beyond ecology. Millions of people worldwide will be forced to relocate to safer areas, while the cumulative damage to the global economy could reach a trillion dollars.

Coastal Erosion Threatens Vast Territories—and Hundreds of Millions of People

Coastal erosion is the gradual destruction of land under the impact of waves, tides, currents, and wind, which wash away sand and soil, erode rock formations, and undermine cliffs. This process has always been part of natural dynamics, but climate change is now accelerating it along several distinct pathways.

First, rising sea levels mean that waves and tides reach higher elevations and far more frequently than before, eroding the upper parts of beaches and the bases of coastal bluffs. Second, the warming of the ocean and atmosphere intensifies storm activity and increases the likelihood of extreme events. Today, a single powerful hurricane can be enough to erase an entire beach or weaken a cliff to the point of collapse. Third, the very geography of erosion is changing—storms are shifting onto new trajectories, waves arrive from unfamiliar directions and grow taller, and in colder regions sea ice is melting, removing a natural buffer that once dampened their force. As a result, risks to settlements, infrastructure, and ecosystems are rising even in areas previously considered stable and safe.

A view of the coastline in the Holderness area of East Riding of Yorkshire in northeastern England. November 13, 2025.

The coastline in the Holderness area. November 13, 2025.

A warning sign alerting to the risk of cliff collapse in the village of Atwick, in the Holderness area. November 13, 2025.

According to scientists’ estimates, between 1984 and 2015 the planet lost nearly 28,000 square kilometers of land to coastal erosion—an area comparable to the size of Belgium or Russia’s Kursk region. Projections point to a further deterioration: if current greenhouse gas emission levels persist, by 2100 some 26% of sandy coastlines could retreat by more than 100 meters, implying the loss of over 52,000 square kilometers of land.

The scale of the impact will affect vast populations. Low-lying coastal zones rank among the world’s most densely populated and economically developed regions. At present, around 680 million people live in these areas; by 2050, that number is expected to exceed one billion. Of the world’s 20 megacities with populations above 10 million, 15 are located in coastal areas, and 40% of the global population lives within 100 kilometers of the shoreline.

Storm-driven erosion in Pismo Beach—a coastal city in California, US, known for its scenic beaches and abundance of seashells (Pismo Beach is even dubbed the “shellfish capital of the world”). As shoreline erosion has intensified, the California Coastal Commission has begun issuing permits allowing private homeowners to build protective seawalls on their property. January 27, 2025.

In the Arctic, Coastlines Retreat by Meters Each Year—While Storms Intensify Erosion Along the Gulf of Finland

Owing to its extensive coastline, Russia is particularly vulnerable to land erosion, which is recorded along nearly half of the country’s maritime borders—about 25,000 of its 61,000 kilometers of coastline. The problem is most acute in the Arctic, where shores are composed of frozen ground. As sea levels rise, water reaches thermokarst zones—areas where permafrost has already begun to degrade, causing the soil to subside and lose density. Wave action accelerates the melting of ice within the ground while simultaneously washing away sand and clay, resulting in especially rapid coastal retreat.

In 2021, researchers at Moscow State University estimated that the Russian Arctic loses around 7,000 hectares of land each year—roughly 70 square kilometers, slightly less than the area of Salekhard. The erosion of frozen ground causes coastlines to retreat at a rate of 1–3 meters per year, and in some locations as much as 5–7 meters. On Arctic islands, these processes are particularly pronounced: on Vize Island in the Kara Sea, land loss in the 1950s was estimated at about 1.5 meters per year, whereas satellite data from 2009–2016 show coastal retreat of 74 meters—an average of roughly 10 meters per year.

A scientist studies erosion caused by permafrost thaw near the Bykovsky Peninsula in the Laptev Sea, Siberia, Russia. 2022.

The coastline of the Bykovsky Peninsula.

Canada’s Arctic Ocean coastline, where coastal erosion and permafrost thaw are underway. 2018.

The Arctic is not the only part of Russia where climate change is driving accelerated coastal destruction. Similar processes are being recorded along the eastern Gulf of Finland, where between 1990 and 2005 the average rate of shoreline retreat was around 0.5 meters per year, reaching as much as two meters in the most vulnerable sections. The greatest damage to the coast is inflicted by storms—in such periods, a beach can shift inland by as much as five meters at once.

Pressure is intensifying as extreme weather becomes more frequent. Between 2004 and 2020, the incidence of storms and other extreme events in the region increased fourfold, a trend that is directly reflected in faster rates of coastal erosion.

The aftermath of a storm on the coast of the Gulf of Finland near the settlement of Solnechnoye in the Leningrad region. The water washes away sand, leaving the beach increasingly rocky. December 2025.

Coastal defenses near the settlement of Solnechnoye. December 2025.

Coastal defenses near the settlement of Solnechnoye. December 2025.

In Africa, Many Coastal Communities Are Especially Vulnerable in the Struggle With the Sea for Land—But the Threat Extends Far Beyond Them

This continent contains the world’s highest share of sandy beaches—around 66%—and in the confrontation with the sea, people are so far losing ground. In Ghana, the coastline retreats by an average of 2–3 meters per year, and by more than five meters in some locations. The reason is that the shore is composed of loose sand and lacks a rocky barrier, meaning that every storm takes on a destructive force. Small fishing villages on a narrow peninsula in the country’s southeast are effectively slipping beneath the water: between 2005 and 2017, one settlement lost 37% of its territory, with thousands of structures—homes, schools, and churches—washed away.

According to a World Bank study, in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo more than half of the coastline is eroding at an average rate of 1.8 meters per year. The combined economic damage to these countries reaches $3.8 billion annually—more than 5% of their GDP. In Nigeria, in the oil-rich Niger Delta, erosion is destroying farmland and entire settlements. In 2020, it emerged that one local town had lost about 60% of its territory—residential buildings and a school were washed into the river.

A view of waves from the Gulf of Guinea advancing toward a house in the village of Avedzi, Ghana. By early spring 2025, storms had destroyed more than 50 homes in the village and forced around 300 residents to leave the area. March 5, 2025.

A sculpture from a cemetery in Avedzi. As the water advanced and coastal erosion intensified, the remains of more than 100 people had to be exhumed and relocated farther from the gulf. March 4, 2025.

A house on the beach in Avedzi. March 5, 2025.

A view of the village of Avedzi. March 5, 2025.

Along the coast of the Republic of the Congo, erosion has taken on not only an environmental but also a cultural dimension—material traces of the past are disappearing together with the shoreline. Powerful Atlantic currents have already severely damaged buildings from the colonial era and a former slave-trading post—a historic site located on the sandy cliffs of the bay. Local residents are also alarmed by the gradual encroachment of the sea on the burial grounds of their ancestors.

Coastal erosion is intensifying in Western countries as well. In the United Kingdom, storm activity is increasingly leading to the collapse of coastal cliffs and the destruction of sandy beaches. Among the settlements at highest risk are villages in Cornwall, Cumbria, Dorset, Kent, on the Isle of Wight, as well as in Norfolk and Sussex. Analysts estimate that more than 2,000 properties, with a combined value of around £584 million, are under threat.

A house in the village of Thorpeness, in Suffolk in eastern England. Part of the settlement is at risk of collapsing into the sea due to coastal erosion. August 19, 2025.

This century-old house in Thorpeness was demolished when the edge of the cliff came within five meters. The 88-year-old owner was unable to do anything to save her property. The photograph shows how reinforcement in one location intensified erosion along the adjacent stretch of coast. October 28, 2025.

A house on the edge of a sandy cliff in the village of Skipsea in the Holderness area of northeastern England. The rate of erosion along the Holderness coast is among the highest in Europe. On average, local cliffs erode at a rate of about 1.5 meters per year, while losses on individual cliff sections can exceed 20 meters annually. Over the past thousand years, the coastline has retreated by roughly two kilometers, leading to the destruction of 26 villages. June 12, 2025.

A crab fisher bails water from his boat after the end of the season in the village of Cley-next-the-Sea in eastern England. This region is among the most vulnerable to coastal erosion in the United Kingdom. November 11, 2025.

In Barcelona, artificial beaches face a constant shortage of sand: according to the city council, annual losses amount to around 30,000 cubic meters—roughly equivalent to the volume of 12 Olympic swimming pools. During storm periods, the scale of erosion becomes even more pronounced.

In the United States, erosion is most acute in Louisiana. Since the 1930s, the state has lost nearly 5,000 square kilometers of wetlands and barrier islands—narrow strips of sand along the coast that function as natural breakwaters—and the area of its coastal islands has shrunk by more than 40%. Louisiana accounts for around 80% of all coastal wetland losses in the country. At the same time, the problem affects other regions as well: since 2020, dozens of homes in North Carolina have collapsed into the ocean. In Alaska, warming has led to the thawing of sea ice and permafrost, stripping Arctic shores of their natural protection from waves, and in some settlements the coastline is retreating by as much as 22 meters per year.

A wave inside a house in the settlement of Avon, North Carolina. Like neighboring Buxton, Avon is located on the narrow Outer Banks—a 320-kilometer chain of small islands and sandbars that are particularly vulnerable to Atlantic storms.

A flooded section of the settlement of Buxton, North Carolina. October 2, 2025.

Island states are among the most vulnerable to erosion. Many are situated on flat coral atolls and narrow sand spits, where even a modest rise in sea level leads to a rapid loss of land.

The Maldives are under threat, with around 80% of their territory lying less than one meter above sea level. In the Caribbean, island states risk losing up to 3,900 square kilometers of land by 2050. In the Pacific, the Marshall Islands could disappear entirely if sea-level rise continues at its current pace.

Tuvalu—a state in the southern Pacific Ocean made up of nine small islands. Here, the threat extends beyond rising sea levels and storms that are gradually stripping residents of land. Warming oceans are driving tuna—the country’s main source of food and income—away from the waters surrounding the islands. In the near future, this problem could have a profound impact on Tuvalu’s population and economy. April 7, 2025.

A boy at the window of one of the houses in the village of Cemara Jaya near the city of Karawang in West Java. Over the past 20 years, the coastline in this part of the island has been eroding, with the water moving ever closer to homes and forcing people either to adapt to new conditions or to relocate to other regions. January 11, 2025.

A destroyed house in the village of Cemara Jaya. Around 145 million people live on Java, making it the most densely populated island in the world. Scientists warn that in the coming years parts of Java could be completely submerged. January 11, 2025.

Children on the porch of a house in the village of Serua on the island of Fiji. July 15, 2022.

A view of a seawall under construction along the coast of Ebeye—one of the Marshall Islands. June 13, 2025.

How to Slow Coastal Destruction—from Building Bans to Seawalls and Relocation

Coastal erosion cannot be stopped entirely: the shoreline is a dynamic system in which sand and water constantly reshape the land. But the pace of destruction can be slowed, and the scale of damage reduced. In practice, three main approaches are used: refraining from placing housing and infrastructure in high-risk zones, protecting coasts with engineering structures, or relocating development farther from the shoreline.

The least costly option is generally the first. In New Zealand, for example, authorities seek to avoid building municipal housing in areas exposed to flooding and other climate risks. This approach does not physically reinforce the coast, but it limits future losses—fewer people and assets are left in danger zones that would otherwise suffer repeated damage from natural forces.

The second path involves directly reinforcing coastal defenses. Denmark, Germany, and the United Kingdom are building and upgrading dikes and seawalls. Such structures can effectively protect individual cities or stretches of coastline, but they come with a significant drawback: they rigidly fix the shoreline and often disrupt the natural movement of water and sand. As a result, protecting one area can accelerate erosion in neighboring territories. Scientists have observed this effect, among other places, in the Gulf of Finland and the Kaliningrad region, where port facilities and breakwaters shield some shores while intensifying land retreat on others.

The Haus Seeblick youth center building, closed due to the risk of a cliff collapse, on a bluff in Travemünde—a district of the city of Lübeck in northern Germany. February 11, 2025.

Like Lübeck, the community of Dagebüll lies in the state of Schleswig-Holstein on the Baltic Sea coast. As storms intensify, some seas—including the Baltic—no longer freeze, eliminating a natural buffer against autumn and winter weather that is increasingly eroding the shoreline. October 24, 2025.

Employees of Schleswig-Holstein’s State Agency for Coastal Protection, National Parks, and Marine Conservation repair damaged sections of a stone coastal defense structure on the island of Hallig Langeneß. January 21, 2025.

A steep Baltic Sea coastline in Latvia near the village of Jurkalne. The house pictured was built in 1993, when it stood roughly 40 meters from the shore. Today, only a few meters separate it from the edge of the cliff. According to Latvian geologists, the country has been losing an average of 15 hectares a year in recent decades as the sea advances. By the end of the century, parts of the Baltic coastline could shift inland by tens of meters. March 2025.

The Netherlands, for its part, has opted for large-scale sand-based “defensive” solutions. Under the Zandmotor (“Sand Motor”) project, 21 million cubic meters of sand were deposited into the North Sea, creating a vast artificial peninsula. It slows erosion and encourages the formation of new dunes. Effective measures, however, do not always require such massive investment. In Catalonia, volunteers install simple wooden sand traps to help restore dunes. Along a stretch of coast where the shoreline had retreated by 50 meters over half a century, the height and extent of dunes increased by 40% within three years after these barriers were put in place.

A view of artificial dunes at the Zandmotor beach near The Hague in the Netherlands. Sea levels in this region are rising rapidly: scientists estimate that by 2150 they could increase by two meters, threatening the city’s very existence. To reinforce the coastline, the “sand motor” technology is used here—large volumes of sand are added to beaches and then redistributed over time by wind, waves, and tides. August 27, 2024.

More natural forms of coastal protection also exist—through the restoration of kelp forests. Dense underwater stands of these algae effectively dissipate wave energy. Computer modeling conducted for two areas of Scotland showed that kelp can reduce wave height by up to 70%, significantly lowering the risk of coastal erosion. Another approach within engineered adaptation involves abandoning attempts to fully restrain the water and instead learning to coexist with it. As an example, South Korea and the Maldives are experimenting with floating residential homes.

A lecturer from the maritime faculty of Bandirma Onyedi Eylul University works during a dive in the Sea of Marmara as part of the CAYIR-IZ project. The initiative aims to protect seaweed meadows, which are a vital component of coastal ecosystems. Seaweeds play a key role in combating climate change thanks to their ability to store carbon and prevent coastal erosion. In addition, seaweed forests provide habitat for numerous marine species. October 6, 2025.

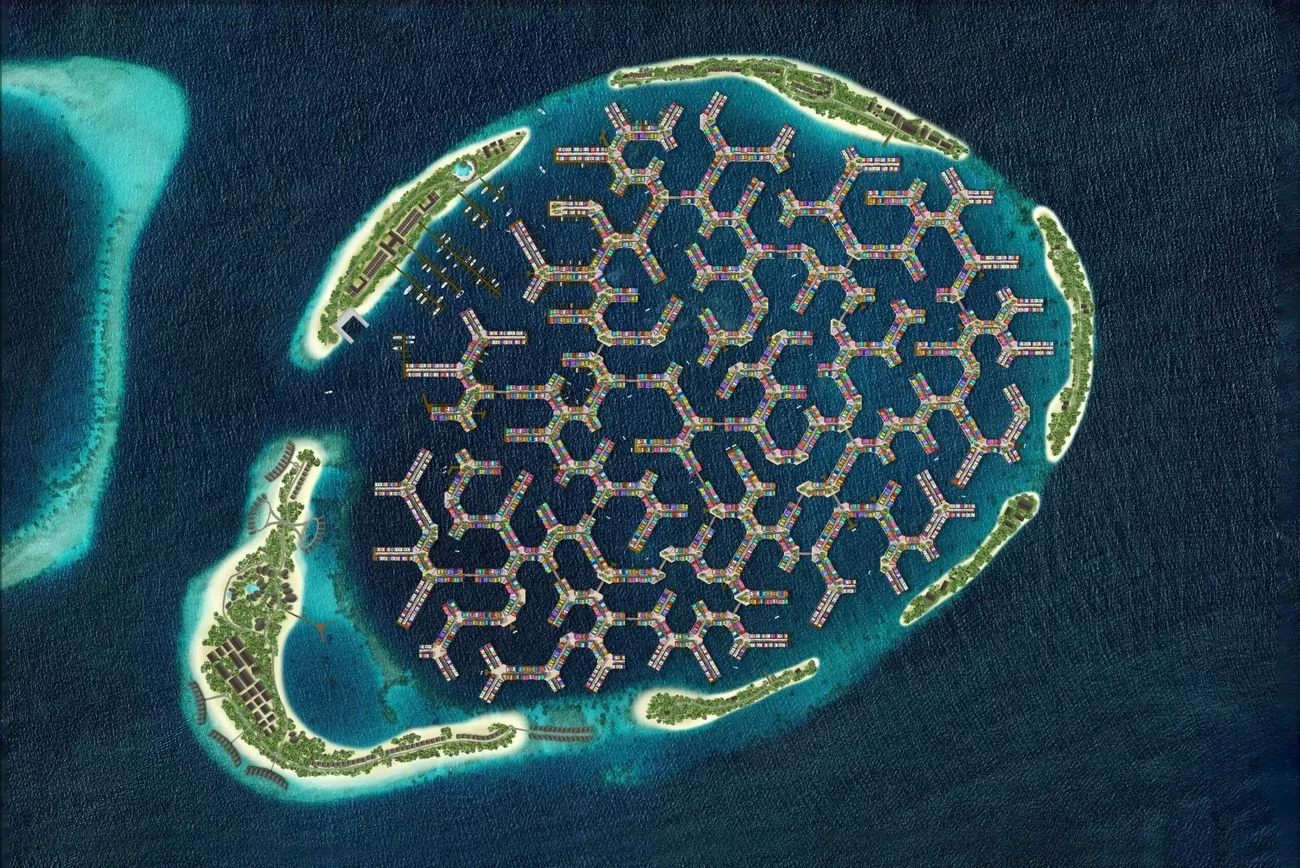

Construction of Maldives Floating City—an ambitious project billed as the world’s first fully fledged floating city-state, located near the capital, Malé. The Maldivian authorities see it as a response to rising sea levels and overcrowding. The city will consist of modular platforms designed to mimic coral structures, with residential buildings, hotels, schools, and restaurants. It is planned to accommodate 20,000 residents. Construction began in June 2022 and is scheduled for completion in 2027.

A view of a section of the Maldives Floating City under construction. April 2024.

Transporting the first floating home as part of the Maldives Floating City project. February 2023.

The third strategy is relocation. On the Pacific island of Fiji, rising sea levels have prompted authorities to plan the relocation of entire villages. This is a form of “managed retreat,” in which the state acknowledges in advance that holding the shoreline has become prohibitively expensive or ineffective, and moves housing, roads, and infrastructure farther inland.

To assess the scale of such retreat, the authors of a 2025 study analyzed changes in nighttime illumination captured in satellite images between 1992 and 2019. They found that in 56% of coastal regions, settlements shifted inland; in 28%, their location remained largely unchanged; and in 16% of cases, development moved closer to the sea. The acceleration of relocation away from coastal zones was most pronounced where erosion risks were higher and infrastructural protection weaker.

One of many fishing villages flooded as a result of rising sea levels in the Khulna region of Bangladesh. Its residents were evacuated to safer parts of the country. July 13, 2025.