Publicly, Vladimir Putin calls relations with China "unshakable" and speaks of a "golden era" of strategic partnership. But within the FSB, assessments are far less optimistic: in one closed counterintelligence unit, Beijing is explicitly referred to as an "adversary."

That unit within Russian counterintelligence views China as a serious threat. According to its officers, Chinese intelligence agencies are actively attempting to recruit Russian citizens and gain access to sensitive military technologies—often through scientists disillusioned with conditions in the country.

The FSB claims that China is closely monitoring Russian military operations in Ukraine to study Western weapons and battlefield tactics. There is also growing concern over Chinese academics, who are allegedly laying the groundwork for future territorial claims in the Russian Far East. In the Arctic, Chinese operatives are said to be working under the cover of scientific and mining enterprises.

These threats are outlined in an internal eight-page document reviewed by The New York Times. The report is undated, but based on its content, it was likely compiled in late 2023 or early 2024. It details the priorities in countering Chinese espionage and offers a rare glimpse into how Russian counterintelligence views Beijing.

The document was obtained by the group Ares Leaks, which has not disclosed its source—making independent verification impossible. However, six Western intelligence services reviewed the file at the request of The New York Times and concluded it was authentic.

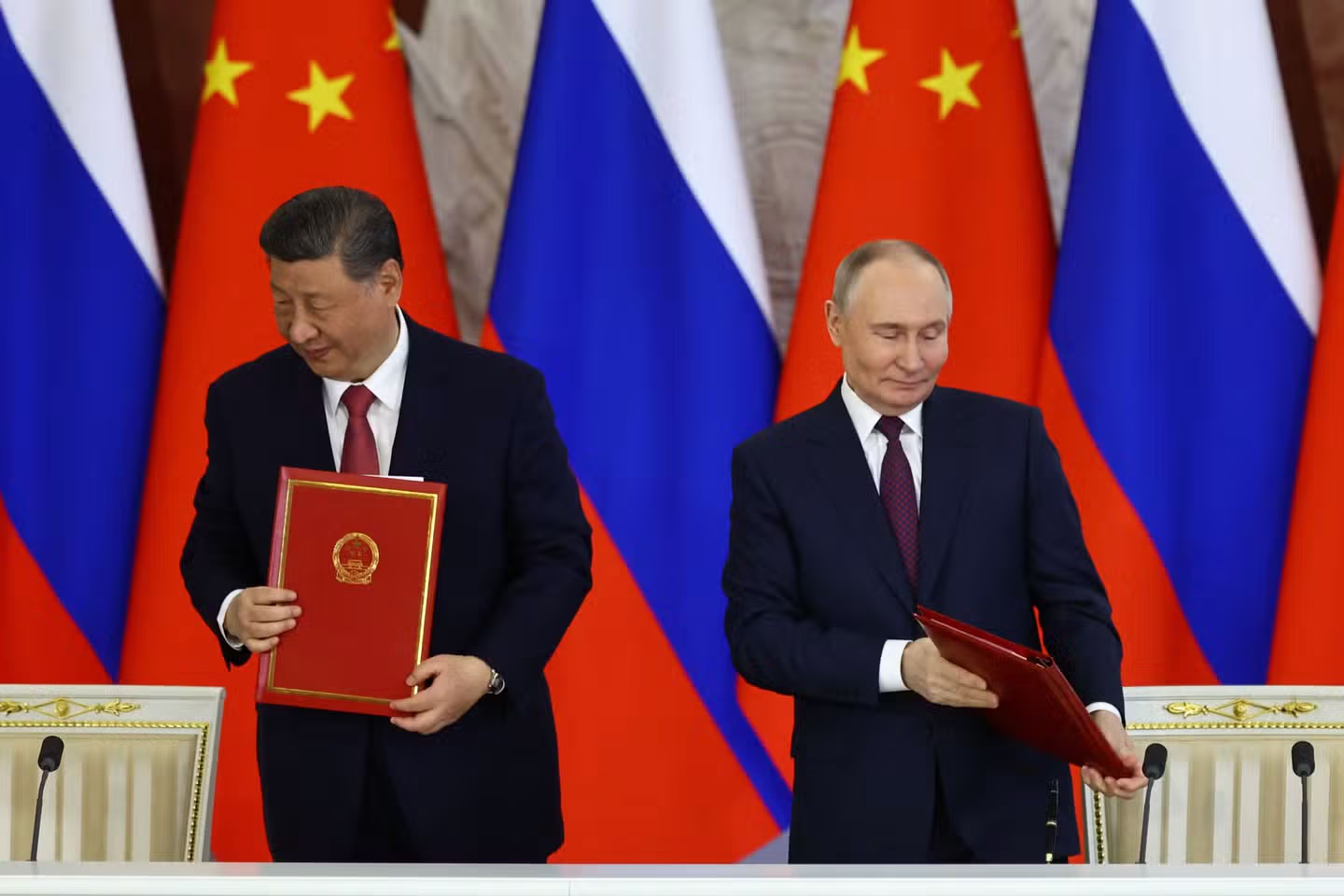

Following the invasion of Ukraine, Russia moved closer to China, reshaping the global balance of power. The partnership has become one of the most consequential—and opaque—alliances of recent years. Moscow has withstood Western sanctions largely thanks to China, now its top buyer of oil and a key supplier of critical components—from microchips to military-grade parts. Chinese brands have replaced Western ones. Joint projects are planned in fields ranging from film production to lunar base construction. Yet despite the rhetoric of a "partnership without limits," the classified FSB memo suggests that limits do exist.

"Russia’s political leadership supports closer ties with China," says Andrei Soldatov, a security services expert living in exile. "But within the intelligence community, Beijing is viewed with suspicion."

Three days before the invasion of Ukraine, the FSB approved a counterintelligence initiative known as "Entente-4"—a name that appears to wryly reference Moscow’s "friendship" with Beijing. Its stated purpose: to counter Chinese efforts to undermine Russian interests. The timing was no coincidence. On the eve of war, Moscow had concentrated nearly all resources on Ukraine and likely feared that China might exploit the distraction.

The FSB claims those fears have been borne out. According to its data, Chinese intelligence has stepped up efforts to recruit officials, experts, journalists, and businesspeople with ties to the Russian state. In response, operatives have been instructed to personally warn Russians who cooperate with Chinese entities about the risk of leaking strategic information, and to monitor WeChat users—including hacking phones and analyzing messages using specialized software.

The prospect of long-term alignment between two authoritarian regimes—with a combined population of roughly 1.6 billion and a joint nuclear arsenal of 6,000 warheads—has raised alarm in the United States. The Trump administration believes that by strengthening ties with Putin, Washington might eventually pull Russia out of China’s orbit. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has described the strategy as a way to prevent a united front of nuclear powers against the U.S. "I’ll have to split them up. And I think I can do it," Donald Trump said on the eve of his election victory.

From this perspective, the FSB document confirms cracks in the alliance. It states that China conducts polygraph tests on its personnel after trips to Russia, has tightened oversight of 20,000 Russian students, and actively recruits Russians married to Chinese nationals.

But another reading is also possible: if Putin is fully aware of the risks yet continues to deepen ties with Beijing, the U.S. may have very limited leverage to alter his trajectory.

"Putin sees closer alignment with Beijing as a calculated risk," says Alexander Gabuev, head of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center. "But the document shows there are voices within the system who don’t trust that course."

Over the years, Putin has met with Xi Jinping more than 40 times in person. Since the start of the war, the partnership has only grown stronger. Economically, it makes sense: Russia is one of the world’s largest energy suppliers, and China is its top consumer.

For counterintelligence, this creates a particular challenge—neutralizing threats from Beijing without jeopardizing bilateral ties. The document emphasizes that any public reference to China as an adversary must be avoided to prevent fallout for the broader relationship.

Based on its structure, the directive was intended for regional FSB offices. It originates from the 7th Directorate of the Department of Counterintelligence Operations, which focuses on China and other Asian countries. The tone is one of alarm: Russia is becoming increasingly vulnerable to Beijing’s growing influence. It remains unclear how widely these concerns are shared across other government agencies. Even allies spy on one another.

"There are no truly friendly intelligence services," says Paul Kolbe, a former CIA officer. "Scratch any officer and you’ll find deep-seated mistrust of China. Despite the alliance, Beijing is still seen as a potential threat."

Since the war in Ukraine began, Russia has seen a steady influx of visitors from Chinese defense contractors and research institutes linked to intelligence operations. According to the FSB, their objective is to study the conduct of the war.

China has strong scientific talent, but its military hasn’t fought a war since 1979. This raises concerns in Beijing: how would its forces perform in a real conflict involving Western weapons—such as one over Taiwan? Chinese intelligence is eager to draw lessons from the war in Ukraine.

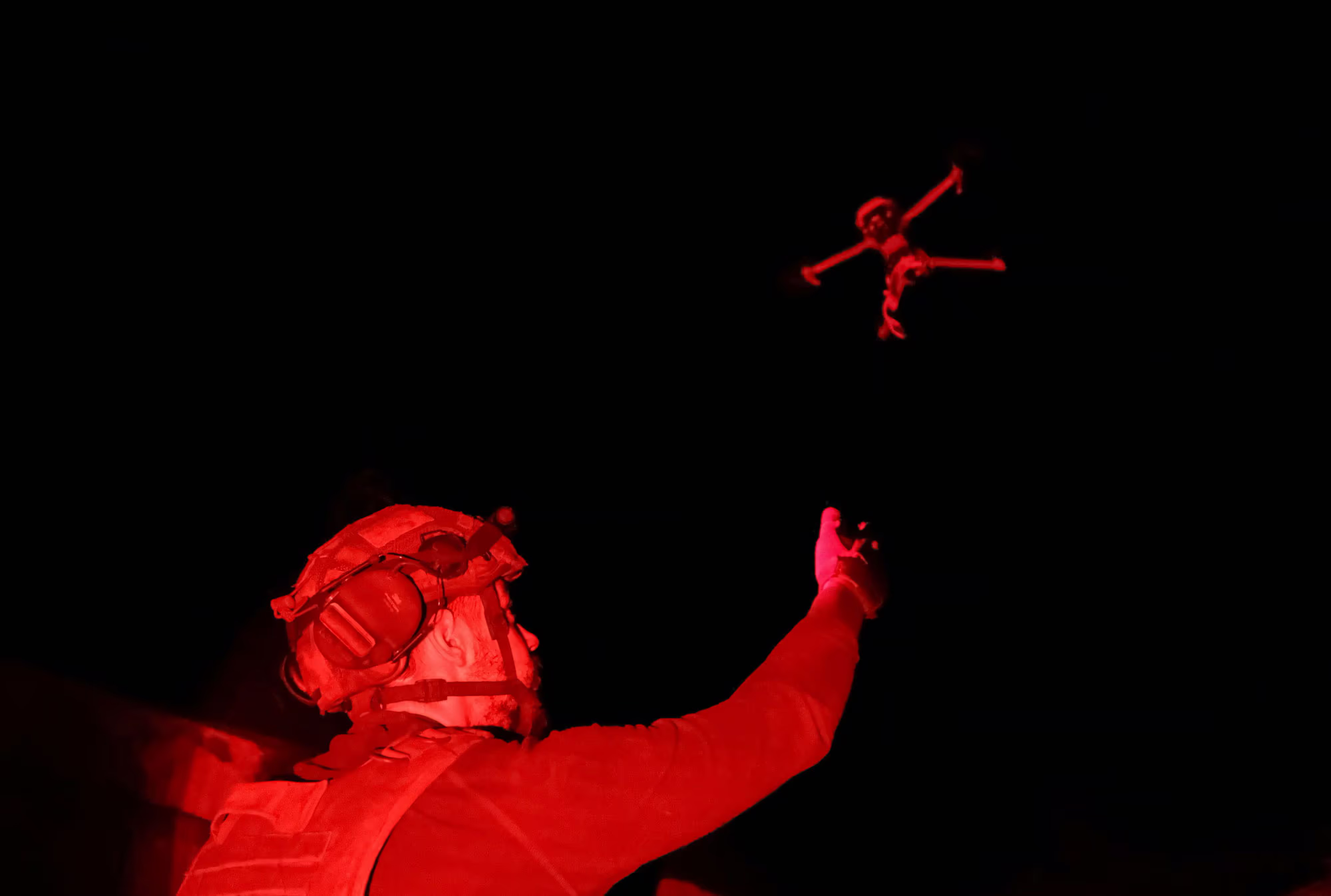

Of particular interest is information related to drone use, software updates, and methods for countering Western military technology. The document notes that Beijing assumes the conflict will be prolonged—and has already revised its understanding of modern warfare as a result.

China is also keenly interested in aviation technologies, a field in which it has traditionally lagged behind Russia. Its focus includes military pilots and specialists in aerohydrodynamics, flight control, and aeroelasticity. According to the FSB, China is also seeking engineers who once worked on the decommissioned Soviet-era ekranoplan program.

A soldier launches a combat FPV drone near the front line in Ukraine.

Priority is reportedly given to former and current specialists who are either disgruntled over the project's closure or facing financial hardship. It is unclear whether this involves recruitment into Chinese research programs or full-scale intelligence activity.

The FSB is deeply concerned about how China interprets the course of the war. Operatives have been instructed to share positive information about Russian military operations with Beijing and to prepare analytical briefs for the Kremlin on possible shifts in China’s position.

Western leaders have repeatedly accused China of supplying critical components for Russian military hardware. The FSB document supports these concerns: Beijing has reportedly offered to create alternative logistics routes to bypass sanctions and has expressed willingness to assist in the production of drones and other advanced technologies. It remains unclear whether these plans were implemented—but the fact stands: China is already supplying drones to Russia.

The document indicates that China has taken particular interest in the combat experience of the Wagner Group—a paramilitary force closely aligned with the Russian Ministry of Defense. According to the FSB, China aims to draw on Wagner’s experience to train its own armed forces and private military companies operating in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The report does not specify whether this involves recruiting fighters or merely adopting their tactics.

Historically, Russia has viewed China’s activities along their 4,000-kilometer shared border with suspicion. In China, reinterpretations of 19th-century treaties—under which Russia annexed vast territories, including Vladivostok—have been under way for years.

Against the backdrop of Russia’s military weakening, these sentiments have taken on new resonance. The FSB notes that Chinese scholars have begun actively searching for "traces of ancient Chinese peoples" in the Russian Far East—presumably to establish a cultural and historical foundation for future territorial claims. In 2023, Beijing published an official map that used historical Chinese names for Russian regions.

The FSB has instructed its operatives to identify such revisionist activity, restrict access to archives, prevent the use of Russian resources for historical justification of claims, and carry out "preventive work" with those involved. It has also recommended denying entry to foreign nationals participating in such efforts.

The FSB’s threat assessment regarding China is not limited to the Far East. Central Asia—traditionally viewed as a Russian sphere of influence—is under close watch. According to the intelligence service, Beijing is implementing a "new strategy" of soft power in the region, first tested in Uzbekistan. Details are scarce, but the initiative is said to center on "humanitarian exchange."

The region remains a priority for Putin, who views the restoration of influence across the post-Soviet space as part of his historical mission.

A separate section of the document focuses on the Arctic and the Northern Sea Route—a once ice-locked passage between Europe and Asia that is becoming increasingly navigable due to climate change. China sees strategic value in the route, which offers significantly shorter shipping times.

Moscow has traditionally sought to limit Chinese involvement in the Arctic, but as the FSB notes, sanctions have forced Russia to turn to Beijing for infrastructure support. Novatek, for instance, has already enlisted Chinese partners for its Arctic LNG project following the withdrawal of the U.S. firm Baker Hughes.

According to the FSB, Chinese intelligence is actively collecting information on Arctic development efforts, operating under the cover of universities and resource extraction companies.

Nevertheless, the document stresses that any action against Chinese entities requires approval at the highest level. Undermining relations with Beijing is viewed as an even greater risk than deepening the partnership.

Allies—Almost

An Alliance Doomed to Asymmetry

Why Strategic Rapprochement With China Is Leading to a New Russian Dependency

Russia Expands Drone Production With China’s Help

Bloomberg Documents Reveal How Chinese Technology Bypasses Sanctions to Supply the Russian Military

China Is Conducting Cyberespionage Against Russia

Despite the Rhetoric of a 'No-Limits Partnership', Beijing Sees Moscow as a Vulnerable Target