Until recently, Russia remained one of the key power brokers in the Middle East. Leveraging ties with Syria and Iran while maintaining relations with Israel, Moscow sought to balance conflicting interests—hosting delegations from Hamas and Hezbollah alongside the Israeli prime minister.

But the political landscape has shifted. Syria now has new leadership, ties with Iran have weakened, and in efforts to resolve the Gaza conflict, Russia has found itself largely sidelined. The long-anticipated first Russia-Arab summit in Moscow was either postponed or quietly canceled. Instead, the Kremlin was left hosting a former adversary—Syria’s interim president Ahmad al-Sharaa—in a bid to salvage some of its lost influence. Moscow still seeks to maintain a foothold in the region, but it no longer holds the role of chief mediator.

The Postponed Summit: How Trump’s Peace Plan Derailed the Kremlin’s Diplomatic Agenda

The inaugural Russia-Arab summit, originally scheduled for October 15, was canceled by Vladimir Putin just five days before it was due to begin. He explained that the meeting—nearly a year in the making—would be rescheduled, though no new date has been set. The Kremlin hopes to hold it in November, while Arab sources are more cautious, suggesting it might not take place before the end of the year.

The official explanation came from Putin himself. “We agreed to postpone our meeting—Russia and the Arab League—on my initiative. I did so because I don’t want to interfere with the process that has now, we hope, taken shape and is moving forward, incidentally, at the initiative and with the direct involvement of President Trump in the Middle East,” he said on October 10, referring to the ceasefire in Gaza brokered under U.S. President Donald Trump’s plan.

Putin’s decision came as a surprise. Just a day earlier, the Russian Foreign Ministry had released an extensive interview with Sergei Lavrov timed to the summit, in which the minister emphasized that Moscow understood Arab states’ concerns about the Palestinian issue but was confident the event would be attended “at the level of heads of state or government.”

Yet within 24 hours it became clear that one of the Kremlin’s main diplomatic events of the year had fallen apart. According to Bloomberg, by October 6–7 too few Arab leaders had confirmed their participation. Among the absentees were Saudi Arabia’s crown prince and de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman, UAE president Mohammed bin Zayed, and Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The cancellations were likely linked to the threat of new U.S. sanctions against Russia—discussed by Trump in early October—and Washington’s irritation over the Kremlin’s stance on the war in Ukraine. Meanwhile, Arab allies of the United States, sources said, enjoyed a rare moment of goodwill from the White House thanks to progress in the Gaza talks.

Events in the region were unfolding at remarkable speed. On September 29, Donald Trump, speaking alongside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, unveiled a 20-point plan for a ceasefire and hostage exchange. Israel publicly accepted the proposals, and soon Hamas—though with reservations—also agreed. After a series of consultations mediated by Egypt, Qatar, Turkey, and the United States, both sides reached a deal, and in the night of October 10 the Israeli government approved the agreement. The ceasefire took effect.

The release of hostages was expected on October 13. By that time, Trump was already preparing a visit to the region, an address to the Knesset, and participation in the hastily arranged Peace Summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, organized with the involvement of the U.S., Egypt, Qatar, and Turkey. These nations declared themselves guarantors of the ceasefire.

This overlap of schedules effectively made the Russia-Arab summit impossible to hold. The foreign ministers of the Arab League countries were due to arrive in Moscow on October 13, but most instead traveled to Egypt. Moreover, the outcome of the Israel-Hamas deal remained uncertain, making any diplomatic planning risky.

Interestingly, the key regional leaders—Mohammed bin Salman and Mohammed bin Zayed—also skipped the Sharm el-Sheikh summit, sending only high-level delegations. Officially, they endorsed Trump’s initiative; however, according to The Middle East Eye, both Riyadh and Abu Dhabi were displeased that Hamas would retain a presence in Gaza, even without formal authority. They were also unhappy that Qatar and Turkey—both of which have strained relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE—played the lead roles in mediation.

The situation is further complicated by internal rivalries among Arab capitals. The UAE had previously proposed initiatives similar to Washington’s, while Saudi Arabia, together with France, promoted the idea of recognizing Palestine and developing a roadmap for its reconstruction. Now, the peace-making laurels have gone to others. Participating in the Moscow summit instead of the U.S.-backed forum would have appeared as a pointed gesture against Washington—a step neither Riyadh nor Abu Dhabi was willing to take, preferring to avoid unnecessary complications.

Putin, it seems, was also reluctant to provoke tension with Trump. Moscow acknowledged that holding a major event at a time when the world’s attention was fixed on the release of Israeli hostages would have appeared inappropriate. The Kremlin’s attempt to present itself as an alternative diplomatic center had lost its relevance, and the absence of an invitation for Putin to the Sharm el-Sheikh summit underscored that diplomatic initiative in the Middle East had temporarily shifted to the United States.

Moscow Loses Initiative but Hopes to Regain Influence Through the Russia–Arab Summit

In Moscow—as well as in Arab capitals and in Israel—there is recognition that Trump’s plan is unlikely to unfold smoothly. All of its provisions, apart from the release of hostages, have provoked disagreements and new disputes among the parties to the conflict. Even the exchange itself proved difficult: Hamas handed over twenty surviving hostages to Israel, while the return of bodies of the dead was delayed. Under these circumstances, Russia can only wait: Trump will enjoy his diplomatic triumph, and then, most likely, the situation will return to its usual course.

As for the Arab states’ concerns about Washington’s sanctions threats—reported by Bloomberg—the region is well aware of how changeable the U.S. president’s moods can be. First came the threats, then a phone call between Putin and Trump, and soon after, talk of a new meeting planned in Budapest.

The conversation between the presidents took place on October 16—on the eve of Volodymyr Zelensky’s visit to Washington. Formally, the call was linked to that visit, but Putin opened the discussion by congratulating Trump on his success in Gaza. The Kremlin understands well how to flatter the American leader—and makes full use of that knowledge.

In Moscow, as among many Middle Eastern partners, attitudes toward Trump’s plan remain skeptical. Yet Russia has no alternative to offer: in Middle East diplomacy it now largely follows the positions of Arab states. As a result, Moscow has adopted a wait-and-see stance, hoping to seize the opportunity to criticize the U.S. initiative—particularly if it manages to host the long-delayed Russia–Arab summit.

The idea for such a summit was first floated in December last year during a meeting between Sergey Lavrov and the foreign ministers of the Arab League in Marrakesh. Similar consultations have been held for more than a decade, roughly every two years, but so far without a top-level format: Moscow’s bilateral ties with Arab capitals had been active enough without it.

The turning point in strengthening Russia’s position in the Middle East came with the 2015 military operation of the Russian Aerospace Forces in Syria. Establishing military bases cemented the Kremlin’s presence and made it a significant factor in regional politics. Although Russia’s trade with Arab and African countries remained far smaller than that of the U.S., China, or the EU, for many in the region Moscow became a useful counterbalance to Western influence.

The situation changed after the invasion of Ukraine. Russia’s involvement in Middle Eastern affairs—and its military capabilities—declined. Moreover, Moscow became partially dependent on the Gulf states, which maintained a deliberately neutral position between it and Kyiv, as well as between Russia and the West. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar have repeatedly acted as mediators on humanitarian issues, including prisoner exchanges. Notably, the first Russian-American contacts after a long pause took place in Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, the Arab monarchies have not curtailed their economic cooperation with Moscow despite U.S. sanctions pressure. They understand that Trump is unlikely to escalate tensions—he values investment and the preservation of business ties with the region.

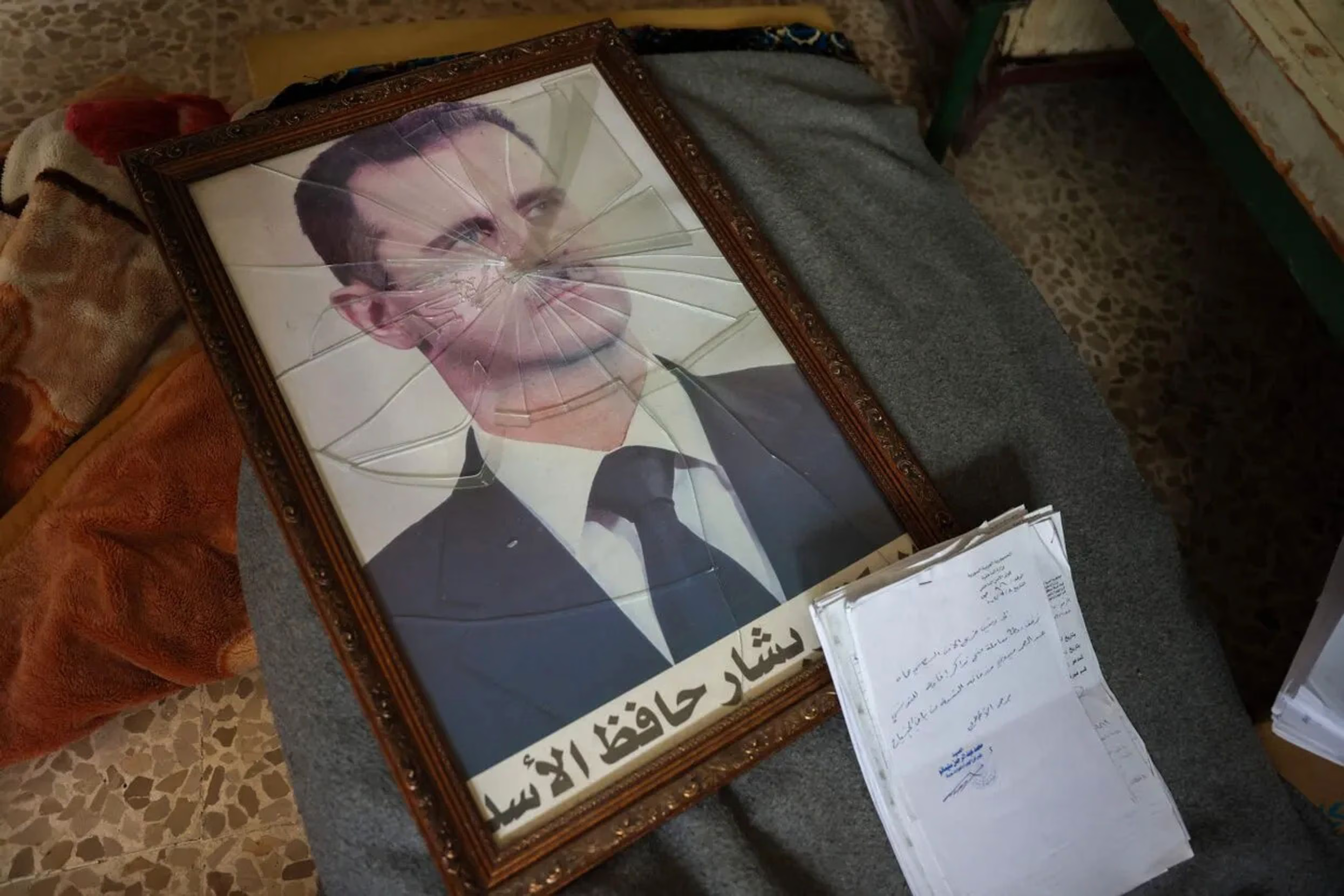

By the end of last year, analysts were predicting that with the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Russia would lose its footing not only in Syria but across the entire Middle East. The reality turned out differently.

Talk of the summit began roughly two weeks after Assad fled to Moscow. Most likely, it was a coincidence—preparations had already been underway for Lavrov’s trip to Marrakesh. One of the aims was to show the West that Russia was not isolated and that cooperation with it continued despite sanctions and political pressure. Yet after the change of power in Damascus, the summit’s importance sharply increased: Moscow now needed to prove that it remained an influential player in the Middle East.

The planned agenda included issues of economic cooperation and the discussion of key regional crises—above all, the war in Gaza. Another topic was to be the creation of a structure that could serve as an alternative to NATO. Whereas Moscow had once sought to halt the alliance’s expansion in Europe, it was now attempting to counter Western influence in Asia.

“NATO now says its mission is to ensure the security of member states’ territories, while the threats come from the South China Sea. They say this quite openly. The alliance is actively expanding its infrastructure in the easternmost part of Eurasia,” Sergey Lavrov noted. According to him, Russia is responding with the concept of a “Greater Eurasian Partnership” as the foundation for a future architecture of continental security. “Our Arab colleagues are promising partners in this process, and we intend to discuss it at the First Russia–Arab Summit,” the minister emphasized.

For now, all these plans are on hold. The timing of the summit will depend not only on developments in the Middle East but also on the state of relations between Moscow and Washington. The Kremlin wants to hold the event in a way that captures global attention; otherwise, its significance will be lost. In the meantime, Russia is projecting confidence through other means, signaling that despite recent setbacks, it still retains a foothold in the region.

The Syrian President’s Visit Becomes a Symbol of Russia’s New, Limited Role in the Middle East

One of the central episodes of the canceled Moscow summit was the visit of Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa. The Kremlin attached special importance to this trip, viewing it as a chance to reinforce Russia’s position in Syria. Despite the summit’s cancellation, the meeting went ahead and ultimately gained a significance of its own—arguably greater than initially intended.

A year ago, such a meeting would have seemed impossible. Al-Sharaa, previously known as Abu Mohammad al-Julani, led Hayat Tahrir al-Sham—a group designated as a terrorist organization by the U.N., the U.S., and Russia. Russian forces had repeatedly struck HTS positions in Idlib, and it therefore seemed that after the faction’s rise to power in Damascus in December last year, Russia’s presence in Syria would come to an end.

Nevertheless, the country’s new leader chose to maintain contact with Moscow despite Western pressure urging him to cut ties with Russia in exchange for financial support. Al-Sharaa explained that Syria intends to build relations with all states willing to assist it—and Russia is among them.

In Moscow, the Syrian president was received with full state honors. According to the newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat, his talks with Putin took place in the Green Drawing Room of the Grand Kremlin Palace—one of its most ceremonial halls. The meeting was given an additional layer of intrigue by the fact that Bashar al-Assad and part of his entourage have been sheltered in Russia since December. Before his visit, al-Sharaa had publicly declared his intention to demand Assad’s extradition, and a Syrian court had even issued an arrest warrant for the former leader.

The public portion of the talks, however, was deliberately restrained in tone. Putin spoke of the “continuity of Russia’s interests regarding the Syrian people rather than specific political figures.” In other words, Moscow made clear that its priority remains maintaining influence in Syria regardless of who holds power. Al-Sharaa, in turn, emphasized the historic nature of ties between the two countries and declared his intention to “reset relations and present the world with a new Syria.”

Behind closed doors, far more sensitive issues were reportedly discussed—the fate of Assad, Russia’s military bases, and compensation for wartime destruction. According to Asharq Al-Awsat, the question of the bases remains unresolved and will require further negotiations at both political and military levels. Some Syrian sources report a preliminary agreement on joint management of the Hmeimim Air Base and the reopening of Latakia Airport.

Syrian Foreign Minister Asaad al-Sheibani later stated that “no new documents have been signed yet” and that agreements concluded under the previous regime have been suspended. Ashhad Salibi, deputy director of the Foreign Ministry’s department, clarified that the meetings in Moscow focused on new legal frameworks for cooperation—including the search for individuals—as well as coordination at the U.N. and Security Council to strengthen Syria’s diplomatic position. According to him, al-Sharaa did raise the issue of Assad’s extradition, though without concrete results.

The Kremlin, for its part, made clear that no extradition would take place. Dmitry Peskov said he had “nothing to add” on the matter. It is likely that Moscow assured Damascus that Assad and his associates would refrain from political interference, leaving the question unresolved—as a useful diplomatic lever. For Damascus, the continued presence of Russian bases serves a similar purpose.

According to Arab media, al-Sharaa may also seek Russian mediation in normalizing relations with the Kurds in the northeast and the Druze in the south. In addition, discussions reportedly touched on the possible return of Russian military police to the Golan Heights. After al-Sharaa’s departure, his foreign and defense ministers remained in Moscow—an indication, analysts say, that the talks are ongoing.

It is possible that the two sides may eventually agree on restructuring and reequipping the Syrian army, including air-defense systems—a topic raised during the Syrian chief of staff’s visit to Moscow a week before the summit. However, such steps would require coordination with regional partners, above all with Israel.

On financial matters, Russia, according to official sources, is ready to write off part of Syria’s debt and continue contributing to the country’s reconstruction. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak said that Russian companies remain interested in returning to the Syrian market.

In practice, Moscow can no longer dictate terms to Damascus, yet it remains an important partner. Russia’s military presence is also advantageous to Israel, which sees it as a stabilizing counterbalance to Turkey’s growing influence.

This “Syrian model” largely reflects Russia’s current position in the Middle East: the Kremlin’s influence is constrained by sanctions and a loss of Western trust, yet Moscow retains the ability to act selectively and is still regarded as a useful interlocutor. For Arab states and Israel, Russia is no longer a dominant power—but a partner that cannot be ignored. Against the backdrop of Trump’s unpredictability, it even appears the more pragmatic and predictable actor.