Discussion of Russia’s "shadow fleet" has once again taken center stage in the EU. For nearly two years, this network of several hundred aging tankers has quietly serviced up to a third of Russia’s budget, and in many European capitals it had begun to be treated as a difficult but established reality. But when a Russian Su-35 fighter escorting one of these tankers violated Estonian airspace, the issue was no longer routine: The European Union must either introduce concrete countermeasures—or settle for yet another round of rhetorical concern.

We’re talking about hundreds of aging tankers transporting oil in violation of sanctions—without flags, insurance, or adherence to international rules. The European Union is considering adding 180 more vessels to its sanctions list, bringing the total to 350. But in light of recent events, it has become clear: formal restrictions are no longer enough. Russia isn’t just evading sanctions—it has begun using its military to protect this illicit logistics network.

Analysts estimate that about 85% of Russia’s oil exports are now conducted via vessels operating in a legal gray zone. As a result, a third of the country’s budget is funded through trade the West has been trying to halt for two years. G7 restrictions—bans on insurance and shipping services for oil priced above $60 a barrel—have proven easy to circumvent. Moscow has built a parallel fleet: more than 500, and possibly as many as 700, tankers flying flags from Panama, Liberia, and other "flag of convenience" states. These ships sail to Asia, primarily India and China, where sanctions don’t apply and few question the cargo’s origin.

For Ukraine, this is far from a theoretical issue. In a conversation with Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, President Volodymyr Zelensky called the shadow fleet one of the key sources of funding for Russia’s war. Stopping it would strike at not just the Russian economy, but the Kremlin’s war machine. Yet even in waters controlled by EU countries, intercepting these shipments has proven difficult.

In early May, Russian authorities detained the Greek tanker Green Admire. Sailing under a Liberian flag, the vessel was en route from the Estonian port of Sillamäe to Rotterdam, following a route that passed through Russian territorial waters. Technically, it violated no rules. But the ship was stopped, and Western diplomats interpreted this as a signal: Moscow is prepared to retaliate with mirror tactics.

Almost simultaneously, Estonia experienced its own incident. The country’s military escorted the tanker Jaguar—likely part of the shadow fleet and already under UK sanctions—out of its exclusive economic zone. The vessel had no visible flag, and its crew refused to provide registration details. Since it was operating near subsea infrastructure, Estonian authorities suspected a potential threat but chose not to board. Instead, the ship was escorted into international waters. During the operation, a Russian Su-35 fighter jet briefly entered Estonian airspace. The violation lasted about a minute, but it was the first such breach in three years and was widely seen as a show of force: Russia is prepared to defend these tankers as part of its strategic infrastructure.

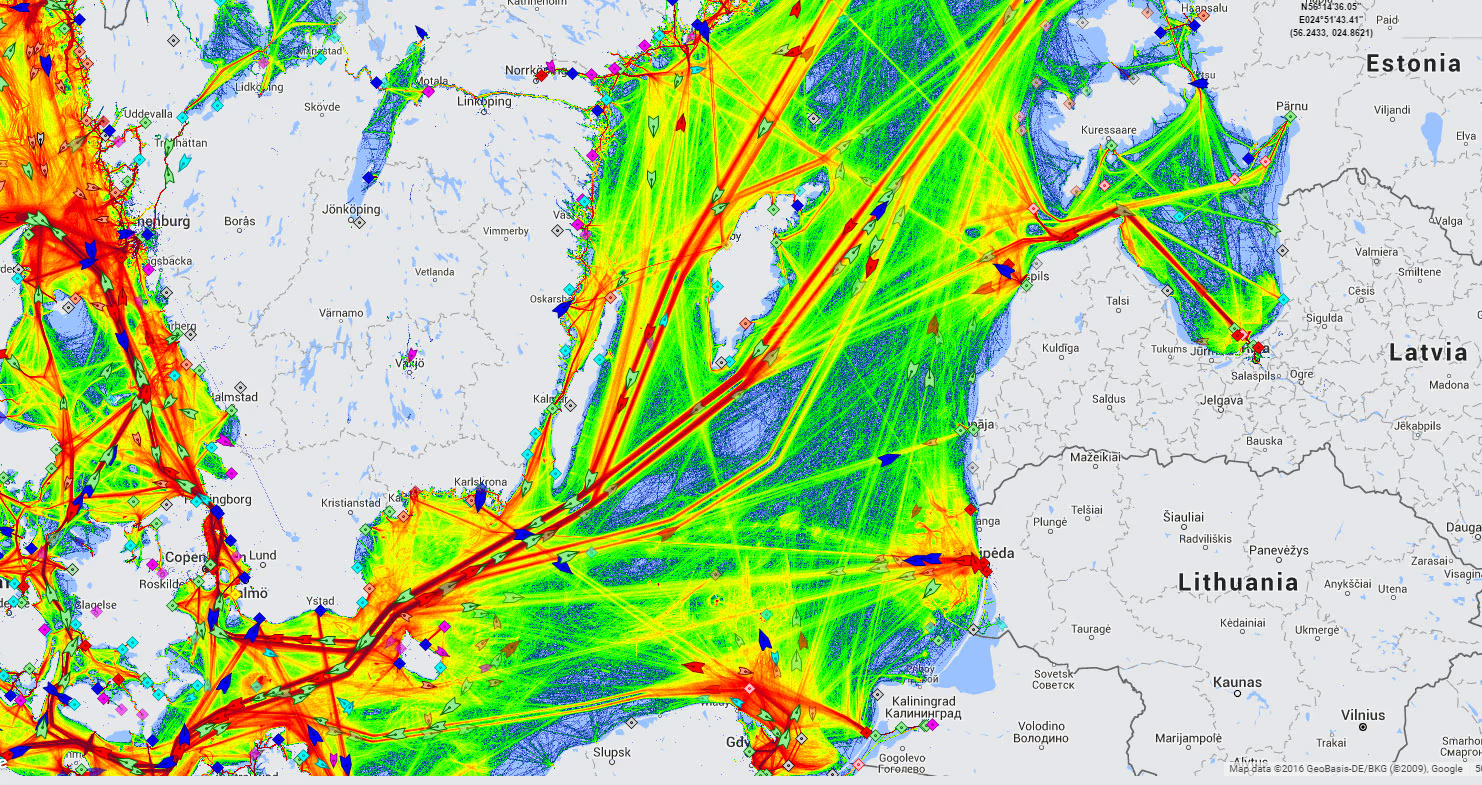

AIS traffic heatmap in the Baltic Sea—showing shipping density and main exit corridors for tankers departing Russian ports.

A modern Russian Su-35 fighter jet.

This poses an uncomfortable dilemma for the European Union. Continuing the current sanctions policy means accepting its ineffectiveness. But tightening enforcement—such as imposing a full ban on these vessels transiting through the EU’s exclusive economic zone—could violate international maritime law.

The European Union already has a toolkit that raises the cost of circumventing the oil embargo—without resorting to direct vessel seizures. First, port and service restrictions: vessels involved in ship-to-ship transfers, AIS signal blackouts, or listed as part of the official "shadow fleet" are denied access to any EU port or dry dock. Second, financial and insurance sanctions: listings of brokers, management firms, correspondent banks, and insurers effectively isolate the shipping ecosystem—even if the tankers never enter European waters. Third, digital monitoring: EMSA combines satellite imagery, AIS data, and drone surveillance; real-time algorithms detect "dark" segments and relay information to port VTS systems, facilitating follow-up sanctions. Fourth lever, pressure on flags of convenience: Liberia, Panama, and the Marshall Islands receive warning letters stating that breaching the price cap could lead to their vessels losing access to European insurance markets. Finally, naval deterrence: NATO’s Baltic Sentry mission patrols key subsea infrastructure routes; under the "reasonable suspicion" doctrine, it can stop and inspect suspect vessels. These tools are legally complex and politically demanding—but their combined effect is already making sanctions evasion costlier and riskier than the potential payoff.

Estonian Police and Border Guard patrol boat.

Lithuanian Foreign Minister Kęstutis Budrys stated in Tallinn that existing enforcement measures are barely working. According to him, Europe fears escalation and is not prepared to take more decisive action. As a result, Russia is expanding its network: the number of shadow vessels is growing, their routes are becoming increasingly brazen, and the risk of provocation is rising. These ships don’t just violate sanctions—they pose inherent dangers. Uninsured and often in poor technical condition, they threaten coastal infrastructure, the environment, and maritime safety.

Against this backdrop, the debate over additional measures is becoming increasingly pragmatic. Proposals already under discussion include stricter monitoring of AIS signals, the creation of a unified watchlist of suspect vessels, pressure on flag-of-convenience states, and the expansion of satellite surveillance. Some of these tools are being implemented by private firms that use AI to track global shipping and sell the data to governments. But without coordinated action at the EU level, these instruments will remain auxiliary at best.

Russia has exploited legal and logistical loopholes to the fullest. Its shadow fleet has become not only a way to bypass sanctions, but a new form of foreign economic pressure—brazen, unofficial, but highly profitable. The question now is whether the European Union is prepared to acknowledge this and develop a strategy that goes beyond a mere list of IMO numbers.

What Are You Gonna Do About It?

Another Test of the Limits

Russia Sends a Warship to Escort Sanctioned Tankers Through the English Channel

Managed Chaos in the Black Sea

How Russia Is Using the Blockade of Ukrainian Ports as a Political Bargaining Chip

The Crimea Deal: How the Bloodless Annexation of 2014 Paved the Way for New Concessions to Moscow

As Kyiv Holds the Front, the West Debates Whom to Blame and Where to Cut Costs