From August 31 to September 2, the SCO summit took place in Tianjin, China, with Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, Narendra Modi, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Masoud Pezeshkian, and António Guterres in attendance. Such meetings usually pass with little fanfare, but this time they drew unusually high attention. Moscow effectively showcased its way out of diplomatic isolation and sought to highlight a shift of the global political center toward the East. The effect was amplified by a military parade in Beijing, which many leaders attended immediately after the summit concluded.

This week’s meetings in China stand out sharply against the backdrop of the G20 summit in Brisbane more than a decade ago. At that time, during the first Russian-Ukrainian war, Western leaders managed to extend their distancing from Putin to include non-Western participants as well.

Anticipating a frosty reception, Putin stopped in China on his way to Brisbane for the APEC summit, where he demonstratively draped a shawl “like family” over the shoulders of Xi Jinping’s wife, Peng Liyuan (she politely removed it). But the G20 atmosphere was far from cordial: the Russian leader was avoided not only by the West—Xi himself preferred to spend time alongside Barack Obama. In 2014, Russian media also published photos of Putin with figures who would later be described as leaders of the “global majority,” yet in reality he was isolated: in the “family photo” he stood on the edge of the front row and left early, before the final statements and documents.

The hard line from the White House also played a role. Obama deliberately kept his distance, refrained from backroom conversations, and persuaded many participants to avoid informal contact with Putin. For many of them, both the aggressive redrawing of borders and the downing of a civilian airliner by a missile were shocking—not only for the West but also for countries of the Global South.

Against the backdrop of Brisbane, Putin’s current position looks like a diplomatic comeback. The war in Ukraine continues—now more open and brutal—but the international setting is entirely different. Instead of leaving early as in 2014, he stayed for an unprecedented four days. Photos with leaders of the “global majority” are no longer mere formalities, and contacts are no longer cautious gestures. For Putin, this has become a kind of compensation for past humiliation.

The main reason for this shift lies in the actions of the current U.S. president. The Alaska meeting, whatever its original intent, gave Putin what Obama denied him after the first war began: the legitimacy of full international engagement. The red carpet and overt hospitality in Anchorage put Global South leaders in a position where they could only compete with Trump in displays of friendliness.

The absence of the American president from the anniversary parade in Asia—an event where the U.S. traditionally cast itself as the principal victor and where that role had rarely been questioned—was another argument seized upon by the Kremlin. Moscow could now claim that true isolation belongs to the West, while the center of global politics and economics has shifted south and east, together with the “global majority.”

Trump himself made matters worse. His remarks carried a tone of grievance and condescension: instead of congratulating China on the anniversary of the war’s end, he reminded the world that it was the United States that had made the decisive contribution and would not allow anyone to “steal” the victory. His final quip—“say hello to Putin and Kim,” supposedly “plotting” against him in Beijing—sounded like the words of a teenager left out of the birthday party of the group’s acknowledged leader or school beauty. The jab only underscored Trump’s shaky position—whether he had chosen to skip the event or had simply not been invited.

Anniversary Summit and Beijing Parade: How the Kremlin Uses World War II to Legitimize War and Rewrite History

Until recently, tones such as “the world underestimates our achievements” or “you will regret not including us” were typical of Putin and his entourage. Now similar notes can be heard in Donald Trump’s words. For the Russian leader, meanwhile, the trip to China unfolded almost perfectly: the 25th anniversary SCO summit coincided with the commemoration of the end of World War II—the Great Victory, which has become the central pillar of today’s Russian ideology, effectively replacing the October Revolution for the USSR.

The SCO itself is hardly a cherished creation for either Xi or Putin. The organization was established under Jiang Zemin, a representative of the “Shanghai clan” with whom Xi had uneasy relations—he eventually dismantled their network and pushed their successors out of leadership. For Putin, the SCO’s birth coincided with a period of relative weakness for both Russia and himself: China took the lead role, and the very fact that the body is based in China and carries the “Shanghai” name underscores the asymmetry.

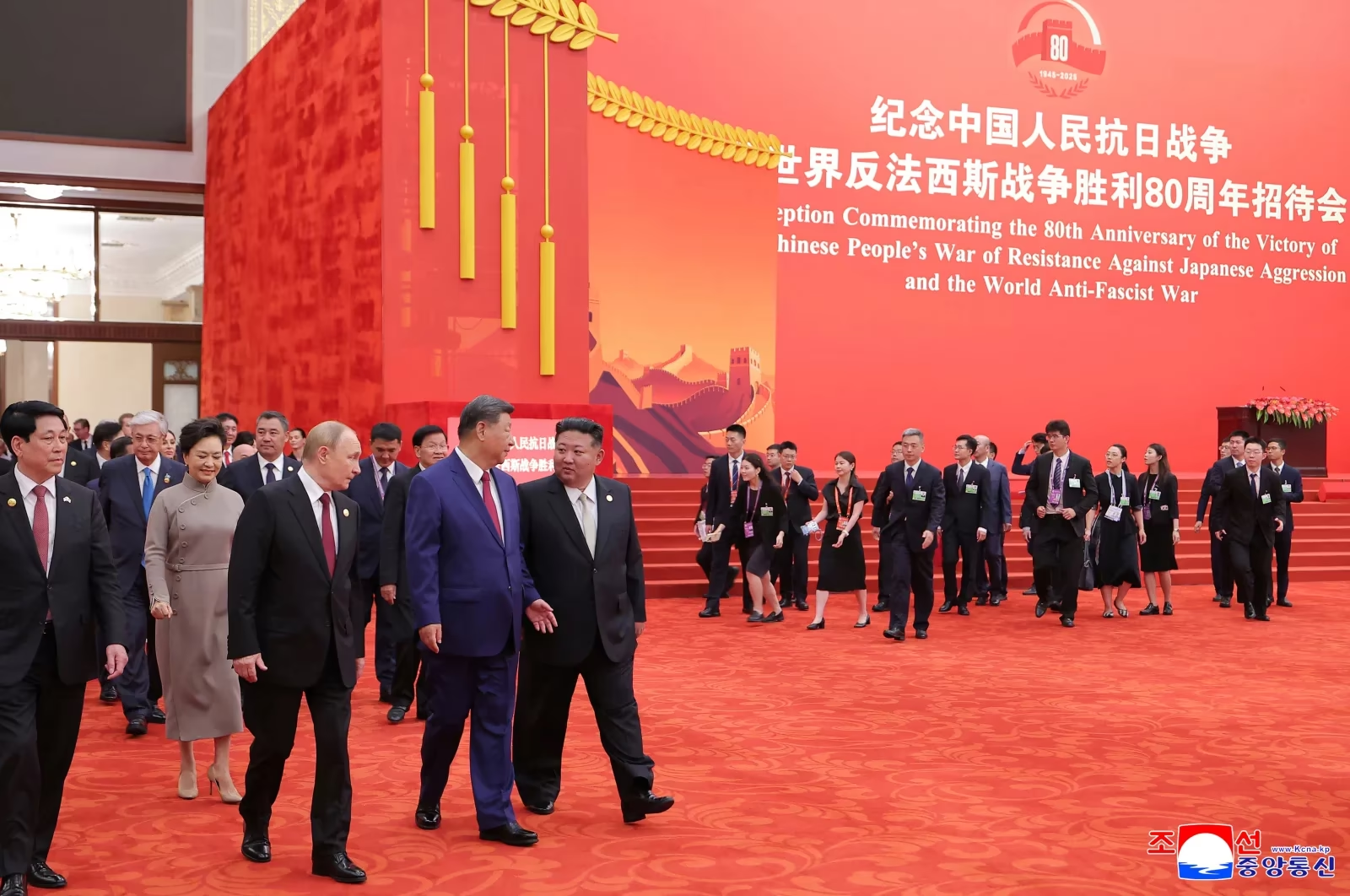

A military parade marking the anniversary of the end of World War II. Beijing, September 3, 2025.

Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, and Kim Jong Un. September 3, 2025.

Moscow has tried to offset this imbalance by inviting new members, but the SCO has never proved effective even when dealing with issues central to its participants—whether the India-Pakistan crisis or the recent brief air war between Israel and Iran. For Putin, what matters more is that the SCO excludes Western countries, and the Tianjin summit flowed seamlessly into the anniversary celebrations of the end of World War II. There he could construct his own narrative, pushing Western allies out even on the “eastern stage of memory.”

An anniversary in Asia without Western participation not only distorted the historical balance but also reinforced the Kremlin’s interpretation of the war. For Russian—and to some extent global—audiences, the images from Tianjin and Beijing were a continuation of Putin’s photo ops from Alaska, and in this light the Anchorage pictures worked against Trump. It became increasingly clear: the Anchorage meeting was not a gesture of goodwill from Putin, but proof that international questions cannot be settled without him. At the same time, Putin and his allies showed they could do without Trump—even at a commemoration directly tied to the United States. For Trump, whose view of national history rests on wars, leaders, and victories, such disregard was particularly painful.

A face-to-face meeting is one of the key resources of American presidents; in Anchorage it is now clear that this tool was wasted, if not counterproductive.

For the United States, taking a softer line toward authoritarian leaders than Europe is nothing new. Washington has traditionally shouldered far greater practical responsibility for global security, which served as justification for less rigid principles. During Francisco Franco’s forty-year rule, no European democratic leader met with him, while Spain hosted two U.S. presidents—Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. Their visits went beyond symbolism: Eisenhower’s agreement integrated Spain into the Western security system and forced the regime to accept new economic rules, hastening the dictatorship’s end; Nixon’s visit bolstered Franco’s successor and smoothed the transition to dismantling the regime.

Nothing of the sort happened in Alaska. Trump squandered diplomatic capital without visible effect and failed to alter Putin’s behavior. Worse, he entered the meeting demanding an immediate ceasefire and left without it—effectively edging closer to the Kremlin’s position.

The Putin-Trump meeting in Anchorage. August 15, 2025.

Both the Kremlin and the White House now pretend they are moving toward a comprehensive peace agreement. But for Russia, this process has always been designed to run in parallel with active combat. Moreover, the proposed deal is meant to cover not only the Russian-Ukrainian conflict but also a broader European and even global agenda, giving Moscow scope to prolong negotiations indefinitely while continuing the war in Ukraine.

The pliant promise of a “soon possible” meeting with Zelensky to end the war—which Trump tried to present as a diplomatic triumph—was swiftly dismissed, first by Lavrov and then by Putin himself. The formula is familiar: “I’m not opposed, but first, the time is not yet right, and second, Zelensky must resolve his own legitimacy issues.”

After the staged photos from Beijing, Putin delivered a long pseudo-legal lecture claiming that the question of the Ukrainian president’s legitimacy had supposedly reached a constitutional dead end with no lawful exit. For Trump, such statements are humiliating: unlike his predecessors, he has never questioned Putin’s own legitimacy—despite his vastly overstretched tenure—and has never refused meetings on the grounds of insufficient preparation or lack of documents.

In essence, Trump entered unprepared talks for the sake of appearances, while Putin, in a comparable situation, pointedly refused. Moscow never considered “rewarding” the host of the Alaska meeting: Russian strikes on Ukrainian cities did not abate but instead grew more frequent and severe.

Neither this nor the tone from Washington had any impact on Putin’s reception in China, or on the rhetoric he delivered there. The recurring hopes that Xi or Modi might relay some “signal” from Trump compelling the Kremlin to shift course and stop unsettling the global order never materialized.

Made in China

A Military Parade in Beijing Gathered China’s Allies and Showcased New Weapons

Xi Jinping Declared That the Country Will Not Accept U.S. Dictates and Warned Taiwan

The SCO Summit Took Place in Tianjin

China Sought to Project Global Leadership, Russia to Show It Is Not Isolated, and India to Signal That Partnership With the U.S. Is No Longer a Priority

Trump Was No Nixon: Concessions to Moscow Strengthened the Russia-China Axis Instead of Weakening It

After Tianjin and Beijing, it became clear that the central justification for Trump’s rapprochement with Putin was an illusion. Unlike Nixon, he failed to drive a wedge between Moscow and Beijing or even to weaken their partnership. The notion that “strategic softness” toward Russia might peel it away from China proved unfounded.

The context is different. Before Nixon’s visit to Mao, China and the USSR were already rivals and openly clashing. Today nothing of the kind exists: the Moscow-Beijing bond appears monolithic. In this environment, a concession to Russia automatically becomes a concession to China. Judging by Trump’s frustrated remarks, he seems to recognize this himself.

In effect, Trump did not pull Russia away from China but instead edged closer to both—shifting his position on a ceasefire in Ukraine, deferring the sanctions question, and weakening even the threat of punitive measures, which now lacks credibility and has long since been priced in by the markets.

Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. September 2, 2025.

The paradox is that in moving closer, Trump also ended up further removed. His absence from Beijing’s Victory anniversary was telling: had he truly made progress in forging a Moscow-Washington line against Beijing, it would have been logical to build on that momentum at the very moment the Russia-China partnership was on full display. There was nothing to consolidate.

Meanwhile, the Putin-Xi bond is visibly stronger than any hypothetical Putin-Trump axis. A potential visit by the U.S. president to China—where Putin was already present for the SCO anniversary—would have looked less like an independent move and more like joining their tandem.

From Strategic Partnership to Balancing Act: Why India Did Not Join the Alliance of Democracies Against China

President Trump not only handed his diplomatic asset to Putin—he also forfeited another important achievement of recent American policy: the rapprochement with India.

The alliance of the world’s largest democracies long seemed natural only on paper. India traditionally remained closer to Moscow, while Washington placed its bets on Pakistan, which often drifted toward authoritarianism. In the early 21st century the dynamic began to shift: New Delhi and Washington deepened ties, and as the Moscow-Beijing axis solidified, India emerged as the weak link in non-Western alignments—precisely why the United States viewed it as a promising partner.

At first, Trump supported this line: in February 2025 one of the first foreign guests at the White House was Narendra Modi — a visit that coincided with the new U.S. president’s high-profile phone call with Putin. At the time, it looked like the launch of a containment strategy against China.

But within half a year the outcome proved the opposite. At the BRICS summit in Kazan in the summer of 2024, Putin managed to bring Modi and Xi to the same table. And after Trump imposed 50% tariffs on India — 25% for trade imbalance and another 25% for Russian oil purchases, effective August 27 — Modi almost immediately traveled to China for the first time in seven years, publicly displaying warm relations with Xi. Putin and Kim smiled nearby.

This does not mean India is severing ties with the United States and siding with autocracies. Rather, New Delhi is solidifying a convenient strategy: balancing between Washington and non-Western formats like BRICS, leveraging their competition for its own benefit. In this sense, India acts much like Russia might have acted—had it not invaded Ukraine. But the myth of a “grand alliance of democracies against China” can now be considered dispelled.

Putin and Trump meet in Anchorage. August 15, 2025.

Even the Paris summit of Ukraine’s allies with Zelensky on September 4 failed to draw attention away: striking images from Tianjin and Beijing and the genuine rapprochement between Beijing and New Delhi overshadowed everything else. Against this backdrop, even the fresh public closeness of the China–Russia–North Korea triangle faded into the background.

Beijing’s celebrations also featured “defectors” from the Western camp — Viktor Orbán and Robert Fico. But imagining Global South leaders at European gatherings in support of Ukraine is inconceivable today: if the United States itself is keeping its distance, why would they attend? Tellingly, Moscow, usually quick to highlight the “Nazi past” of its European critics, had nothing to say about the presence of leaders from states that in fact fought on the defeated side.

One could note that neither the actual effectiveness of the SCO nor the tangible economic, military, or political outcomes of the celebrations appear particularly significant. Yet details such as China’s unilateral decision to lift visa requirements for Russians—without a reciprocal step from Moscow, which says it is still “studying the matter”—look like a generous concession. For Russia, the symbolism is striking: in visa negotiations it has traditionally insisted on reciprocity. For citizens cut off from familiar Western destinations, however, the decision carries direct and positive consequences.

In diplomacy, what matters is not only the concrete result but also the image created. Such multilateral events are designed to shape impressions that linger in the eyes of the wider world.

The only opportunity to offset this effect lies ahead at November’s G20 in Johannesburg. Whether Putin will attend remains uncertain: the ICC arrest warrant, South Africa’s rigorous legal system, and security risks all weigh heavily. Since the start of the invasion of Ukraine, he has avoided flights over international waters and non-allied states.

Yet regardless of whether Putin appears in South Africa or stays home, it is Trump who will have to overcome the cool reception. He must prove that international isolation does not apply to him and that he retains working relationships with other world leaders. To do so, he will likely have to seek photographic and rhetorical validation from the very same Putin, Modi, and Xi.