In December 1954, a group of American sectarians calling themselves the Seekers were convinced that extraterrestrials would arrive from outer space in the coming days and evacuate them from Earth, which they believed had little time left. On the appointed date, nothing happened. Two years later, psychologists Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schachter published a study that became a scientific bestseller—“When Prophecy Fails.” By examining the Seekers’ response to the collapse of their expectations, they formulated the concept of cognitive dissonance, which is still used to explain behavior in cults and authoritarian regimes. In November 2025, independent researcher Thomas Kelly published an article accusing Festinger and his colleagues of unethical methods and questioning their conclusions. A significant share of the academic community, however, rejected this criticism.

The Seekers cult was founded by a 54-year-old homemaker. She claimed to communicate with aliens and the spirit of Christ

The Seekers group took shape in 1953. Its founders were Charles Laughhead, a physician and lecturer at Michigan State University, his wife Lillian, and Dorothy Martin, a homemaker from a Chicago suburb. All three shared an interest in occult teachings. The Laughheads developed this interest after a trip to Egypt, where they engaged in missionary work, while Martin’s views were shaped largely by theosophical literature. A further influence came from the recently emerged Scientology and the book “Oahspe. A New Bible,” written by dentist and spiritualist John Ballou Newbrough. He claimed the text was produced through automatic writing, with his hand supposedly guided by a higher power, and insisted that the book contained the true history of humanity.

A spread from The Pittsburgh Post featuring photographs of Dorothy Martin and Charles Laughhead. 1954.

Following the logic of conspiracy theories popular at the time, the Seekers fused an eclectic set of occult ideas with ufology—a quasi-scientific doctrine centered on unidentified flying objects. Martin claimed she could communicate with other levels of existence. According to her, she first received and deciphered messages from her deceased father, and later allegedly began communicating with incorporeal beings from the planets Clarion and Cerus. All of these messages, it was claimed, were transmitted through the same method of automatic writing that Newbrough said underpinned “Oahspe.”

Martin also claimed that among her extraterrestrial interlocutors was a spirit known in earthly life as Jesus Christ. He allegedly warned her of impending global catastrophes. According to these revelations, the Earth’s crust was to split, causing Lake Michigan to overflow and flood Chicago, while the eastern United States would be torn in two. From the Pacific Ocean, the messages said, the mythical continent of Lemuria would rise, and France, the United Kingdom, and Russia would sink beneath the water. All of these events, Martin asserted, were expected by the end of 1954.

The Seekers met regularly for collective sessions that resembled a cross between church services and UFO-enthusiast gatherings. The teachings of Martin and the Laughhead couple attracted around twenty followers. Most shared a belief in extraterrestrial civilizations and hoped to make contact with them. They regarded the end of the world as inevitable and imminent, believing that only the initiated would be saved—those permitted to leave Earth.

Citing revelations from the spirit of Christ, Martin announced a precise date for the catastrophe—December 17. Nothing happened. The Seekers then began keeping nightly vigils outside Martin’s home, awaiting the arrival of the aliens. Rumors of an impending “departure” quickly drew press attention, and journalists gathered at the house. On the night of December 20–21, 1954, Martin reported a new message: supposedly, the higher beings had decided to spare the planet thanks to the strength of the followers’ faith. Soon after, however, she announced yet another doomsday date—the evening of December 24, Christmas Eve.

Under the latest instruction, cult members were to go outside and sing Christmas carols while awaiting a UFO. After spending several hours in the freezing cold, the Seekers returned to the living room of Martin’s house. By morning, when it became clear that no one was coming for them, participants drifted back to their homes. A few weeks later, the movement had effectively ceased to exist, surviving only as a small circle of the most committed adherents. In 1955, they left Illinois. Martin continued writing esoteric texts under a new name—Sister Thedra.

A year later, in 1956, the long-dissolved Seekers unexpectedly gained widespread notoriety, first in the United States and then beyond it—thanks to the work of psychologist Leon Festinger. It emerged that in late 1954 he had sent several colleagues to infiltrate the cult, posing as UFO enthusiasts, in order to observe Martin’s followers from within. The researchers wanted to see how the sectarians would respond to a failed prophecy and a UFO that never arrived. Festinger and his co-authors set out the results of these observations in “When Prophecy Fails,” a book that soon became a scientific bestseller.

Dorothy Martin and Charles Laughhead in December 1954.

To describe the sectarians’ reaction to failure, Festinger introduced the concept of cognitive dissonance. His conclusions seemed unassailable

“A person with convictions is hard to disabuse,” Leon Festinger wrote in “When Prophecy Fails.” “Tell him you disagree and he will turn away. Show him facts or figures and he will question their sources. Appeal to logic and he will fail to grasp your point of view.”

Festinger and his co-authors offered the following explanation of this mechanism. When beliefs collide with reality, a person enters a state of cognitive dissonance. To relieve the internal tension, one can either abandon those beliefs or, if they are too deeply entrenched, reinterpret events themselves. Once the aliens failed to appear, the Seekers were forced to make precisely this choice.

In their study, the psychologists described in detail the views and behavior of cult members both before the anticipated departure from Earth and after it fell through. Even before December 21, Festinger advanced a hypothesis: some of Martin’s followers would turn away from the teachings after the prophecy failed and return to ordinary life, while the most committed would attempt to rationalize the failure—by citing an error in the date, a misreading of the messages, or a change in the aliens’ plans.

This prediction proved correct. When nothing happened on December 21, the Seekers began searching for explanations that would reconcile expectation with reality. The book includes, among other things, the account of one participant who claimed to have seen among those gathered outside Martin’s house “a spaceman wearing a helmet and a large white cloak.” According to him, this spaceman remained invisible to “nonbelievers.”

According to Festinger’s theory, the wider the gap between the Seekers’ beliefs and reality, the more insistently they sought to persuade others of their correctness. The researchers used this to explain the cult members’ active engagement with the press and their attempts to notify journalists in advance about the rescheduling of the UFO’s arrival. The psychologists attributed the sect’s eventual collapse not to the followers’ disillusionment but to the absence of new charismatic leaders capable of sustaining the movement.

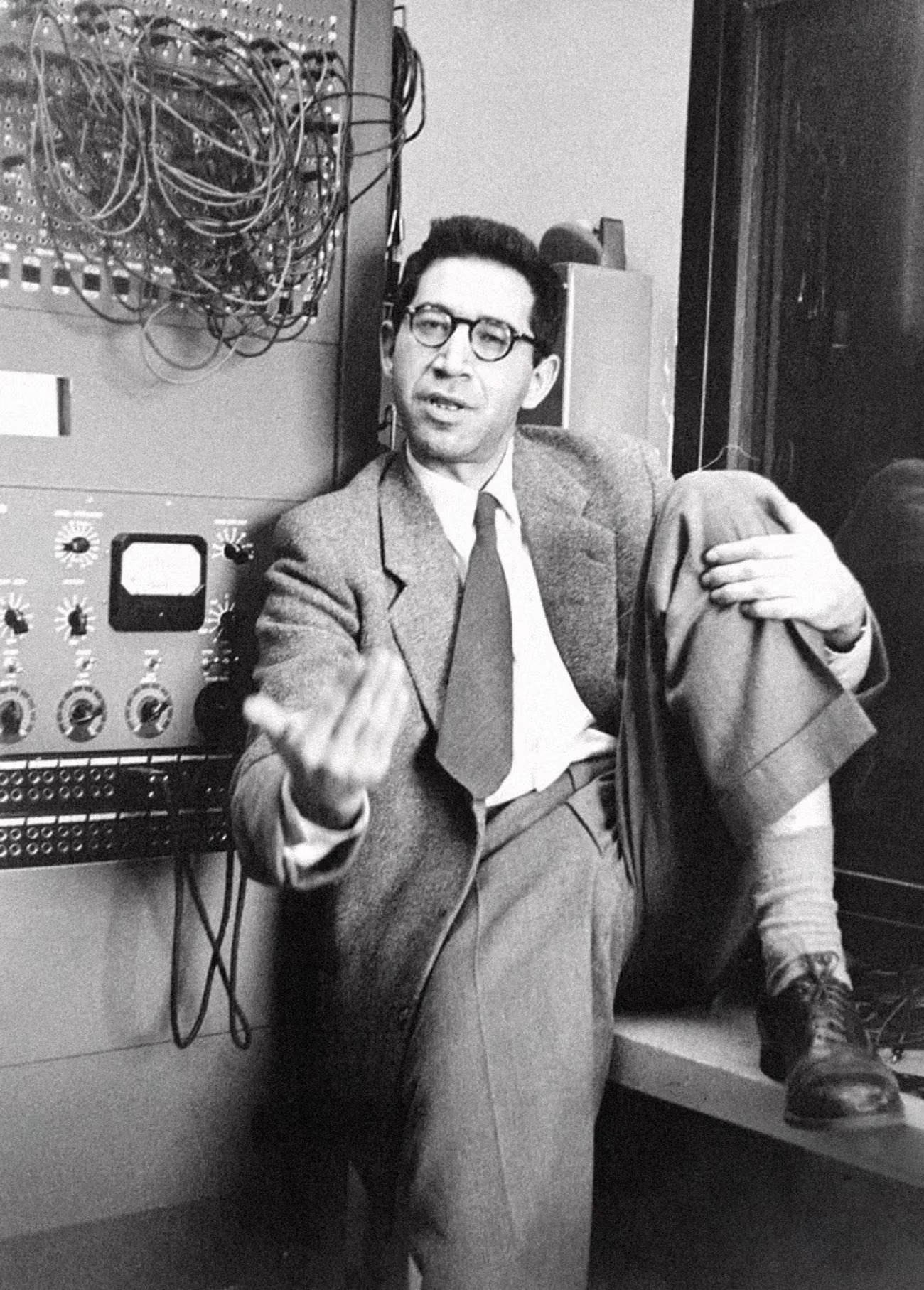

Leon Festinger. 1954.

“It is interesting to speculate about what might have awaited them had they possessed more effective apostles,” Leon Festinger and his co-authors Henry Riecken and Stanley Schachter wrote. “The debunking of their beliefs might not have marked an end, but rather a beginning.”

Since then, scholars have repeatedly invoked the concept of cognitive dissonance in efforts to explain behavior in cults and dictatorships—communities in which ideological constructs and propagandistic narratives systematically diverge from reality. As an illustration of this logic, the conspiracy-theory researcher Arthur Goldwag cited the image of “a Stalinist who continued to believe that Russia was a bastion of freedom and justice even after the purges and the Gulag became known.”

Psychologists secretly infiltrated the cult and manipulated its members to produce the desired outcome. Thomas Kelly argues that this renders their conclusions untenable

In November 2025, Thomas Kelly published an article titled “Debunking ‘When Prophecy Fails,’” in which he argues that the conclusions Leon Festinger and his co-authors drew about the Seekers cannot be trusted.

Kelly holds conservative views, runs a blog on the Substack platform, and occasionally contributes to right-wing media. As Mother Jones has noted, Kelly himself can also be accused of sympathies toward conspiracy theories. In particular, in a piece for the conservative magazine Tablet, which focuses on news from the Jewish community, he endorsed the lab-leak theory of COVID-19.

Kelly describes his reassessment of Festinger’s book as a “side project.” He says that several years ago, after reading “When Prophecy Fails,” he noticed a number of contradictions. The book’s authors claimed that before the prophecy of the aliens’ arrival failed, the Seekers made no attempts to convert outsiders. Yet the examples cited in the book itself, Kelly argues, suggest the opposite. Martin readily shared accounts of her visions with journalists and with anyone willing to listen. Charles Laughhead, for his part, damaged his relationship with the university by trying to promote the Seekers’ teachings among students and by circulating descriptions of them to members of the press.

Suspecting a deliberate massaging of the facts, Kelly decided to scrutinize the book in full for other inconsistencies. He ultimately concluded that the authors distorted information about the cult in order to bolster Festinger’s already articulated theory of cognitive dissonance.

In early 2025, Kelly gained access to Festinger’s working notes preserved in the archives of the University of Michigan. These materials, he argues, show that Festinger and his colleagues resorted to unethical methods—specifically, that they sought to deliberately manipulate the Seekers in order to elicit the reactions they wanted. In one episode Kelly recounts, citing the psychologist’s own notes, the researchers entered Dorothy Martin’s house through the back door, hoping to find something that might prove useful for the experiment. This incident is not mentioned in Festinger’s book.

One of Festinger’s co-authors, Henry Riecken, deliberately worked his way into a prominent position within the sect so that his words would carry authority. When the aliens failed to appear at the time announced by Martin, Riecken used his status to openly mock her and the content of her messages. He then told Charles Laughhead that he was experiencing a crisis of faith and asked for help in convincing himself once again that a UFO would soon arrive. In response, Laughhead declared: “I have renounced everything. I have burned all bridges. I have turned my back on the world. I cannot afford to doubt. I must believe. There is no other truth.”

Riecken then returned to the group and announced that he had managed to overcome his doubts. Martin took this as a sign and, with renewed fervor, set about working on a text that later became known as the “Christmas Message.” In Kelly’s account, it was Riecken’s actions that served as the indirect trigger for the events of late 1954. “Martin’s desperation, Laughhead’s display of faith, and the Christmas Message—all of it happened because of Riecken,” he writes.

Another participant in the experiment, Liz Williams, whom Festinger hired to infiltrate the Seekers, pretended that she too was experiencing visions. In one of them, she said, a “mysterious glowing man” rescued her from a “raging torrent.” In reality, Kelly argues, Williams was merely trying to instill certain ideas in the cult’s members that could later be recorded in the study. According to him, members of Festinger’s group openly reveled in how easily they were able to manipulate the Seekers.

In one episode, Kelly contends, the psychologists’ intervention went beyond the bounds of the experiment itself. When Laughhead’s concerned sister contacted child-protection services to ask whether he and his wife were capable of caring for their children, Festinger’s team intercepted the social workers, explained the study to them, and persuaded them not to intervene. As a result, no inspection was carried out and the case was effectively shelved.

Kelly sees the central problem in the fact that, by infiltrating the sect, the psychologists violated a fundamental scientific principle—the obligation to remain impartial and not to influence those under observation. He also calls Festinger’s conclusions into question. In Kelly’s view, the cult’s members in fact lost their faith fairly quickly: some returned to ordinary life, while others, as in the case of Dorothy Martin, turned to developing alternative belief systems.

“Dorothy Martin fully distanced herself from those events,” Kelly writes. “She even rewrote the story of how she acquired her telepathic abilities.” He notes that Festinger and his co-authors could have verified this themselves had they attempted to contact Martin while working on the book, but they did not. In Kelly’s view, none of this supports Festinger’s claim that the Seekers sought, at all costs, to preserve their worldview to the very end.

Kelly’s conclusions failed to persuade everyone. Many scholars argue that he fits the facts to his own theory—in other words, that he does precisely what he accuses Festinger’s team of doing

Pulomi Saha, an associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies the relationship between cults and mass culture, disagrees with the article’s arguments. According to Saha, in criticizing Festinger, Kelly relied on a “narrow reading of a limited number of archival materials.” In other words, he did exactly what he accused the psychologists of—forcing the data to conform to conclusions reached in advance. Saha also raises concerns about Kelly’s use of ChatGPT to decipher a fragment of Dorothy Martin’s note from Festinger’s archives, written in faded ink. Citing the chatbot’s response, Kelly claimed that Martin referred to Riecken as “the beloved son of the Most Divine.” Yet, Saha emphasizes, no reviewer would consider conclusions based on an AI interpretation to be reliable.

Saha notes that Festinger’s ideas had been subject to criticism in academic circles long before Kelly’s article appeared. “His book is treated as an intriguing study,” she explains. “But it was never regarded as a foundational psychological theory.” In her view, Kelly does raise interesting questions, but they do not justify rejecting Festinger’s conclusions. Rather, these debates help clarify how sharply the methods of contemporary research differ from the practices of the mid-twentieth century.

A similar position is taken by Thibaut Le Texier of the European Center for Sociology and Political Science. “Academic standards in the 1950s were significantly lower than they are today,” he notes. At the time, he says, studies were approved without the safeguards and oversight that would now be required. As a telling example, Le Texier points to the 1971 Stanford experiment led by social psychologist Philip Zimbardo.

Even so, Kelly and his critics agree on one point: the article itself does not undermine the core tenets of cognitive-dissonance theory or demonstrate its invalidity. As Saha emphasizes, one cannot conclude that all the Seekers abandoned their beliefs simply because they ceased interacting with the press and returned to their previous lives.

“The theory of cognitive dissonance has been corroborated in many other cases,” Thibaut Le Texier says. “There is a vast and persuasive body of literature on the subject. You cannot discard the entire concept because of problems with a single experiment. This [Kelly’s conclusions and reasoning] may raise questions about the integrity of particular authors and cast a shadow over their other work. But the theory of cognitive dissonance itself endures.”