From 2026, Polish authorities will require developers to include bomb-shelter facilities in most new residential and commercial buildings. The decision reflects the scale of the challenge facing a country on Europe’s eastern flank—the urgent need to modernize its civil-protection system amid the threat posed by Russia.

Poland, which has endured several Russian invasions in its history, remains today one of the primary targets of Moscow’s hybrid operations. Last month, the country narrowly avoided mass casualties after a railway line was sabotaged; investigators say individuals linked to the Kremlin were involved. In September, NATO fighter jets shot down Russian drones that had violated Polish airspace.

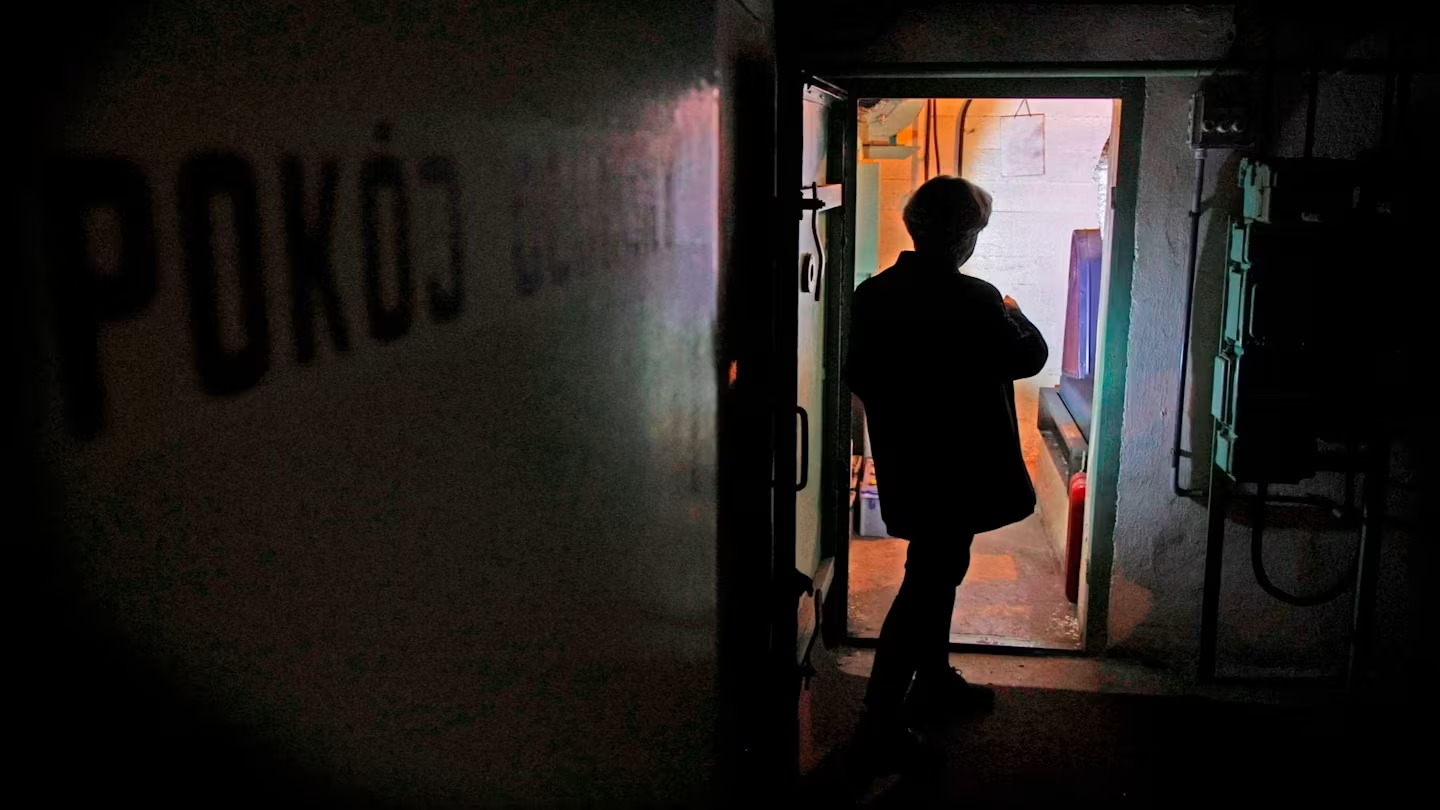

These incidents exposed a critical vulnerability in the national security system. Despite Poland being one of NATO’s leaders in military spending—nearly 5 percent of GDP—civilian protection has long been treated as a secondary priority. Most shelters date back to the communist era and are now in a critical state.

“This is a gigantic problem,” said Slawomir Cenckiewicz, head of Poland’s National Security Bureau and a key adviser to President Karol Nawrocki. “We genuinely need to strengthen the resilience of civil society…in recent years, Poland has focused on modernizing its armed forces and neglected this area.”

President Karol Nawrocki, center, during a visit to the Merihaka civil-defense shelter in Finland.

Beyond changes to construction legislation, Donald Tusk’s government has allocated 16bn zlotys (€3.8bn) in this year’s budget for the construction of shelters. Municipalities are also contributing: several cities, including Warsaw, are directing their own funds toward upgrading and expanding existing infrastructure.

In December, Warsaw’s mayor, Rafal Trzaskowski, announced a project to convert the capital’s metro system into a shelter capable of accommodating up to 100,000 people. If necessary, the plan предусматривает the installation of folding beds, supplies of drinking water, and blankets.

In shaping its approach, Warsaw is closely studying Finland’s experience—a country with the longest border with Russia among NATO members and a network of roughly 50,000 bomb shelters. In September, Karol Nawrocki visited an underground shelter beneath Helsinki capable of housing up to 6,000 people. Inside are cafés, a children’s play area, a volleyball court, and a gym. “For Poland and its citizens, it is critically important to introduce similar mechanisms,” he said after the visit.

Just hours after those remarks, drones entered Polish territory, marking the most serious confrontation between Russia and NATO since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. This episode, combined with the railway sabotage, sharply intensified public anxiety over the safety of the civilian population.

Against this backdrop, Poland has also begun to reconsider its stance on universal conscription, which for many years remained taboo because of memories of compulsory service in the armies of the Soviet bloc. According to a United Surveys poll conducted last month, nearly 60 percent of respondents said they would approve of military service.

At present, only about 1,000 shelters are deemed fit for use—enough to protect no more than 3 percent of the country’s population. By comparison, Finland’s civil-protection system is capable of safeguarding at least 80 percent of its citizens.

Yet Poland is not Finland. With a population of around 37 million, it is more than six times larger than its northern neighbor. The existing network of shelters is clearly insufficient, and most buildings were not originally designed to allow for the rapid installation of bomb shelters.

An additional risk factor is the country’s role as a key logistics hub for the delivery of western weapons to Ukraine, making it a particularly vulnerable target.

At the same time, businesses are beginning to see new opportunities in the situation. In October, the Polish construction company Atlas Ward formed a joint venture with Temet—one of Finland’s leading manufacturers of blast-resistant doors and shelter ventilation systems.

“I wouldn’t say that Poland is too late, but it is good that it has finally woken up,” said Juha Simola, Temet’s chief executive, noting that it took Finland 70 years to reach its current level of protection. “Building a shelter system for Poland’s entire population will take a very long time.”

Last month, the western city of Poznan hosted the country’s first exhibition dedicated to civil protection. Among the displays was a tubular module designed to be buried in a garden and intended to accommodate a family of four.

Poland’s civil-protection law came into force in January last year, but detailed building regulations have yet to be developed—even as only weeks remain before developers are required to incorporate shelters into new projects. Experts warn that without stringent standards, a significant share of the funds could be wasted.

As Markku Bollman, a senior executive at Temet, noted, building shelters is highly specialized work, and vague requirements risk opening contracts to companies that lack the necessary expertise.

Even if the current law is far from perfect, it “at least offers a chance to get started,” said Jaroslaw Gromadzinski, a recently retired Polish general. “We expanded our cities without thinking about how to protect people in a crisis.”

In his view, prioritizing the development of the armed forces was justified. Yet it is becoming increasingly clear that protecting the civilian population is a task “not as simple or as quick as buying weapons.”