Amid the war in Gaza, Europe is experiencing an unprecedented surge in antisemitism—the most extensive since World War II. The number of recorded incidents has already doubled compared to the peak levels of 2014–2015. Experts warn that this is no longer about fringe expressions of hatred. Antisemitism is entering the mainstream, becoming part of public discourse and uniting disparate forces—from the far right and far left to radical Islamists—under a shared rhetoric.

On March 8, 2025, tens of thousands took to the streets of Paris for the traditional International Women’s Day march. But instead of a show of solidarity, the event exposed deep divisions within the feminist movement. Members of the group Nous Vivrons ("We Will Live"), who speak out against antisemitism and in support of Jewish women subjected to sexual violence during the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack, were isolated from the main procession.

In the days leading up to the march, social media saw calls to exclude so-called "Zionist" participants. On the day of the demonstration, police cordoned off the Nous Vivrons contingent, preventing them from joining the main rally. According to eyewitnesses, pro-Palestinian activists blocked their access to Place de la République while chanting anti-Israeli slogans.

"On March 8, 2025, neo-feminism turned into antisemitism—in the name of the Palestinian cause," wrote a columnist for Le Figaro.

Records of Hate

France’s Jewish community—the largest in Europe, with an estimated 440,000 people—is living under growing anxiety. According to Rabbi Shmuel Lubecki of Rouen, a sense of insecurity has become part of daily life, particularly within his congregation, which has faced multiple threats in recent years.

In May 2023, the synagogue in Rouen was targeted in an arson attack: a 29-year-old migrant from Algeria threw a Molotov cocktail at the building and attempted to stab police officers responding to the alarm. The attacker was shot dead, and the early hour meant no lives were lost. But the attacks didn’t stop there. In early 2025, both the synagogue and the rabbi’s home were vandalized—swastikas were painted on the walls along with graffiti calling for "Jewish rapists to be sent to the gas chambers."

Antisemitic graffiti appeared on the walls of a synagogue and the rabbi’s residence in Rouen in early January 2025.

Some young Jews have already left France for Israel, and many others are seriously considering emigration, according to Rabbi Shmuel Lewitzy. Antisemitic sentiment in the country has reached its highest level in decades and has surged particularly sharply amid the war in Gaza.

According to a joint study by the Fondapol think tank and the American Jewish Committee (AJC), 76% of French respondents in 2023 said antisemitism was widespread in France—up from 64% in 2022. Among Jewish respondents, that figure rose to 92% (up from 85% a year earlier). Nearly all expressed concern for their safety: 86% said they feared becoming victims of antisemitic violence after the Hamas attacks on October 7.

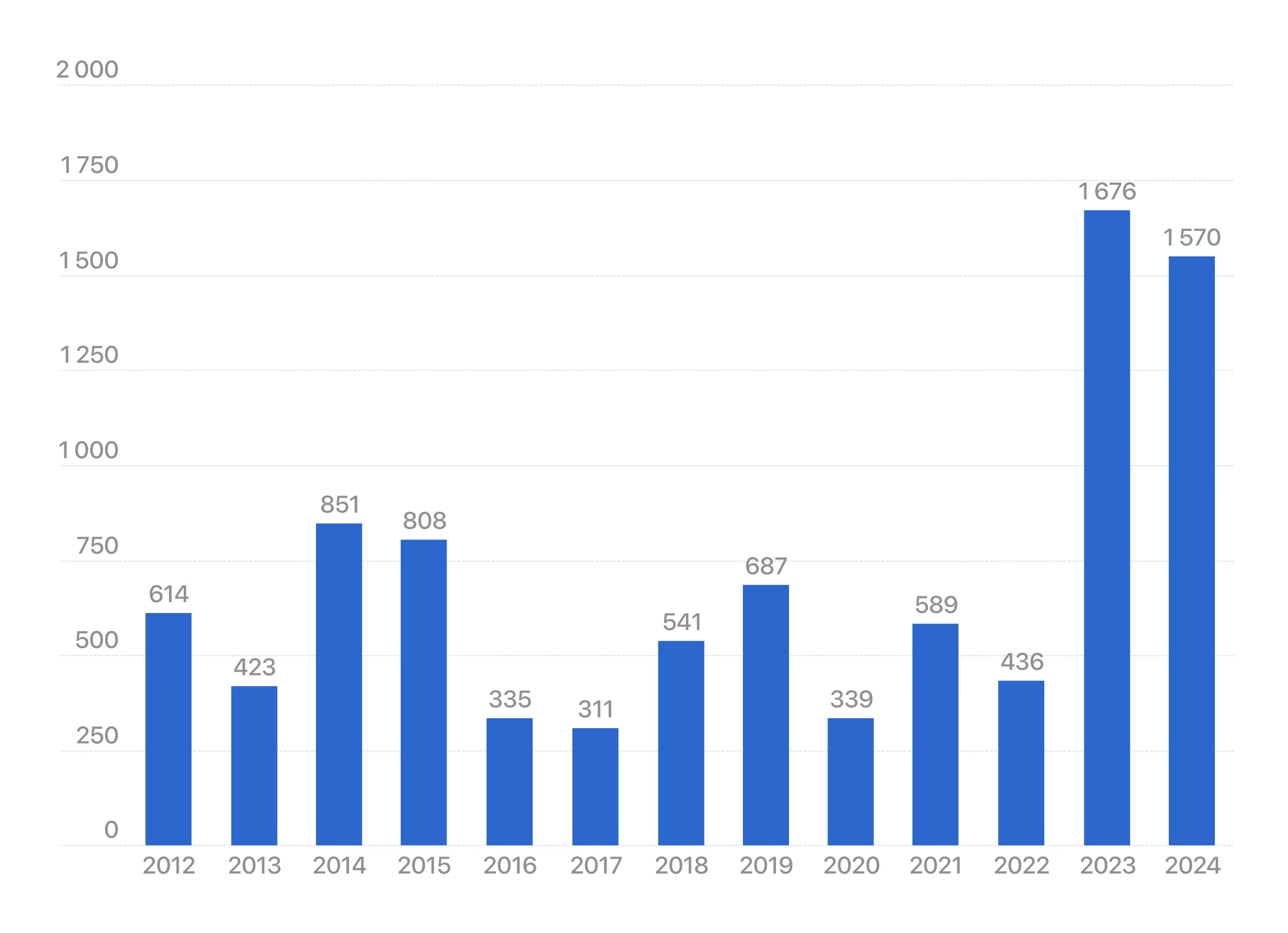

The Service for the Protection of the Jewish Community in France (SPCJ) recorded more than 1,600 antisemitic incidents in 2023—more than in the previous three years combined. Over 1,200 of them occurred in the last three months of the year, following the Hamas attack. By contrast, just 107 incidents were reported during the same period in 2022. Eighty-five of the 2023 cases involved physical violence.

In 2024, the SPCJ recorded 1,570 antisemitic acts, including 106 assaults—the highest number in the past decade.

Trend in Antisemitic Incidents in France Since 2012

In June 2024, an elderly Jewish woman was assaulted in the street: two unidentified assailants knocked her to the ground, kicked her, and hurled anti-Semitic slurs including, "Dirty Jewess, this is what you deserve!" That same month, three teenagers beat and raped a 12-year-old Jewish girl. Her attackers likewise called her a "dirty Jewess" and threatened further violence. In January of last year, a group of six people shouting "Zionist fascists!" assaulted two Jewish students at the University of Strasbourg. In December 2023, a knife-wielding man stormed a Jewish kindergarten in a Paris suburb, threatening the headmistress with rape and mutilation while referencing the October 7th massacre. That October in Grenoble, a Jewish family's apartment was ransacked; burglars left graffiti reading "Free Palestine," swastikas, and threats against Jews on the walls.

France recorded 1,570 anti-Semitic incidents in 2024—the highest tally in a decade. Physical violence accounted for 106 cases. Experts warn that the rise in latent anti-Semitism, not manifesting in overt acts, is equally alarming. According to a September survey commissioned by the Representative Council of French Jewish Institutions (CRIF), 12% of French citizens view Jewish emigration from the country as positive—double the 6% figure recorded in 2020. Among those under 35, this sentiment rises to 17%.

Particular concern surrounds the views of French youth: according to the same data, 14% of respondents in this age group express sympathy for the terrorist group Hamas. "This runs counter to historical trends. It turns out that young French people today are more susceptible to antisemitic, Islamist, and conspiratorial ideas actively circulating on social media," notes CRIF President Yonathan Arfi.

A series of sociological studies conducted after the start of the war in Gaza have confirmed the depth of these biases, especially within France’s Muslim community. Thirty-one percent of respondents believe that "Jews are wealthier than most French people," 27% agree that Jews "exploit the memory of the Holocaust," and 25% believe they have "too much power in the economy and finance." Among French Muslims, more than 50% agree with these statements.

Overall, nearly half of the French population (46%) agreed with at least six out of sixteen antisemitic tropes—from myths about a "global Jewish conspiracy" to stereotypes of dual loyalty, wealth, and influence over politics.

These figures are echoed by global data. According to a study by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), which surveyed over 58,000 people across 100 countries, 46% of adults worldwide hold "deeply entrenched" antisemitic views. A decade ago, that figure stood at just 24%.

As in France, young people worldwide appear most receptive to antisemitic narratives: 40% of respondents under 35 (compared with 29% of those over 50) agree with the claim that "Jews are responsible for most of the world’s wars."

"A Fire That Has Gotten Out of Control"

A similar situation has unfolded across other European countries since October 2023. Fearing for their safety, many Jews have stopped attending Jewish institutions, removed religious symbols such as kippahs or Stars of David, taken down mezuzahs from their doors, and even hidden their names on mailboxes. Harassment, aggression, and threats have affected not only observant Jews but secular ones as well.

"We are fighting for the very survival of Jewish life in Europe," said Menachem Margolin, head of the European Jewish Association, a year ago. "People wearing traditional clothing or visibly displaying Jewish symbols are being attacked. Jewish students are receiving threats, being excluded from university programs, and the walls of homes, synagogues, and cemeteries are once again covered in xenophobic graffiti."

One of the most shocking incidents occurred in November 2024 in Amsterdam, when pro-Palestinian demonstrators began targeting Israeli football fans. The attacks were coordinated: Israelis were tracked outside their hotels, beaten, pushed into canals, and even rammed with cars. More than 20 people were injured. In Israel, the episode was described as a "Jewish pogrom."

Supporters of the Israeli football club Maccabi were attacked in Amsterdam after a match against Ajax. The masked assailants shouted pro-Palestinian slogans.

Not all such incidents make headlines—most come to light only through reports from organizations that monitor antisemitism. In London, a group of teenagers pelted a school bus carrying Jewish students with stones and garbage; several of them managed to board the bus, shouting "Fuck Israel, nobody likes you!" while filming the frightened children. In Zurich, a teenager of Tunisian origin stabbed an Orthodox Jew. In Copenhagen, a subway passenger spat on Denmark’s chief rabbi and gave him the middle finger. In Vienna, members of a neo-Nazi group assaulted a man wearing a kippah. In Ghent, Belgium, a court acquitted writer Herman Brusselmans, who had written in a column that a photo of a crying Palestinian child "whose mother lies under rubble" made him want to "plunge a sharp knife into the throat of every Jew he meets." Despite public outrage and a hate speech lawsuit, the court sided with "freedom of expression."

In the United Kingdom, home to around 270,000 Jews, 2023 set a record for antisemitic incidents. Of more than 4,300 recorded cases, over 2,700 occurred after October 7. In 2024, the overall number dropped to 3,500, but remained 1.5 to 2 times higher than in previous years. Physical violence was involved in 6% of cases.

In Germany, where about 120,000 Jews live, over 2,200 "politically motivated antisemitic crimes" were recorded between October and December 2023—more than four times the number during the same period the year before. By the end of 2024, the total number of such incidents had reached roughly 4,500. "Today, Jewish life in Germany is under greater threat than at any time since the Shoah," said Federal Commissioner for Combating Antisemitism Felix Klein. "Antisemitism permeates all levels of society."

A sharp rise in antisemitic sentiment has also been reported in countries with small Jewish populations—including Switzerland, Austria, the Czech Republic, Ireland, and across Scandinavia—according to international monitoring reports.

A mural in Belfast depicts Israeli soldiers as dark silhouettes against a backdrop of dead children in Gaza. May 2024.

Ireland stands out in particular, having taken the most hardline anti-Israel position in Europe after October 7. The Irish government not only formally recognized the State of Palestine but also endorsed a resolution accusing Israel of committing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. Later, Dublin joined South Africa’s case against Israel at the International Court of Justice. In response, Israel announced the closure of its embassy in the Irish capital.

Additional controversy in 2024 was sparked by a report from the non-governmental organization Impact-se, which monitors educational materials. Several Irish school textbooks were found to contain serious distortions of historical fact and biased narratives on Jewish-related topics. One textbook, for instance, described the Nazi death camp Auschwitz as a "prisoner of war camp"; another claimed that Jews are "people who do not like Jesus," while Judaism was portrayed as a religion that justifies violence and war.

"Pro-Palestinian marches, political rhetoric, media coverage, and especially antisemitic incidents in schools and universities are causing anxiety and disorientation within the Jewish community," says Maurice Cohen, head of the Jewish Representative Council of Ireland. He emphasizes that antisemitism in Ireland has deep roots: historically, the Irish have tended to identify with the perceived weaker side in a conflict.

Prior to 1948, this identification fostered sympathy for Jews fighting the British Mandate in Palestine, much like the Irish themselves struggled for independence. But over time, that sympathy shifted to the Palestinians, seen as resisting "Israeli colonialism." In the 1970s and 1980s, the Irish Republican Army even maintained contacts with the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Experts stress that the rise in antisemitic sentiment in Europe and beyond is not a new phenomenon—and not always directly linked to Israel’s actions. The turning point, they say, came in 2000, with the outbreak of the Second Intifada and the collapse of peace talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority. According to Jean-Yves Camus, director of the Observatory of Political Radicalism at the Jean-Jaurès Foundation, the number of antisemitic acts in France rose from 82 in 1999 to 744 in 2000 and 974 by 2004. While those numbers later declined, they never returned to 1990s levels—not even during periods of relative calm in the Middle East.

One factor behind the latest surge was COVID-19. In 2020–2021, conspiracy theories about a "Jewish plot" supposedly behind lockdowns and vaccination campaigns spread globally. By 2023, even during a lull in regional violence, the number of antisemitic incidents continued to rise—particularly in countries with large Jewish communities, such as the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy. According to a report from the Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry at Tel Aviv University, this shows that "the war in Gaza merely poured fuel on a fire that had long since spun out of control."

Israel as the Collective Jew

In a 2015 interview with The Atlantic, French Prime Minister Manuel Valls warned that alongside the "old" right-wing antisemitism, a "new" variant had emerged—rooted in migrant communities from the Middle East and North Africa, where anti-Israel sentiment often morphs into hatred of Jews. Over the past two decades, researchers confirm, most deadly attacks on Jews in France have been carried out by individuals from Muslim backgrounds.

Yet neither Islamists nor the far right are the sole purveyors of this ideology today. Increasingly visible is radical anti-Zionism—an ideological form of antisemitism that denies Israel’s right to exist and demonizes the very notion of Jewish statehood. This stance is propagated both by Islamist extremists and segments of the far left, including in cultural and academic circles.

"Open expressions of antisemitism are no longer seen as shameful as they once were. In some cases, they’ve even become fashionable," notes Carole Nuriel, head of the Middle East division at the Anti-Defamation League (ADL). She attributes this to a shift in rhetoric: "Today, many identify as anti-Zionists and claim to hate Zionists, not Jews. But make no mistake: anti-Zionism is a form of antisemitism. Zionists are simply those who believe the Jewish people have a right to their historic homeland." According to Carl Yonker of the Center for the Study of Contemporary European Jewry at Tel Aviv University, "Denying the Jewish people’s right to self-determination, declaring Israel’s existence illegitimate, or calling for its destruction—this is no longer a political stance, it is antisemitism."

This is precisely why, in the view of the ADL, the slogan "From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free" cannot be seen as merely anti-Israel. It calls for the total elimination of Israel as a Jewish state and, in its most extreme interpretations, ethnic cleansing of Jews. The phrase stands in direct opposition to the internationally supported concept of "two states for two peoples." In several European countries—including Germany (Bavaria), the Czech Republic, and the Netherlands—it has been officially designated as hate speech and incitement.

Anti-Zionist rhetoric—framed as a struggle against colonialism and genocide—has a long and politically driven history. As explained by Ksenia Krimer, a historian of Judaism and the Holocaust at the Leibniz Centre for Contemporary History in Potsdam, the roots of this ideology lie in Soviet propaganda of the late 1960s. The USSR systematically portrayed Israel as an aggressor and exported this narrative abroad—through propaganda channels including Western communist parties and allied states.

"It’s striking how leftist ideologies absorbed this Soviet discourse in its most reductive form," says Krimer. "On one side, there’s the supposedly powerless victim engaged in an act of ‘resistance’; on the other, Israel as the ruthless occupier and embodiment of evil. In this black-and-white framework, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict becomes the world’s defining moral struggle—even at the expense of attention to other tragedies involving violence or discrimination by Arab or Muslim states. The kind of sympathy extended to Palestinians is rarely expressed toward Uyghurs in China, Afghans in Pakistan, or victims of wars in Sudan and Yemen."

Professor Monika Schwarz-Friesel of the Technical University of Berlin, an expert on contemporary Judeophobia, emphasizes the deep-rooted nature of this hatred. In her words, Israel has become the "collective Jew" in the eyes of antisemites—the target of all the historical myths once directed at Jews as a people. "Motifs of alleged child murder, land theft, and the destruction of other nations—centuries old—are now projected onto the State of Israel," she notes.

In her view, the Middle East conflict is not the cause but merely the pretext. Antisemitism predated the founding of Israel and will not vanish with the end of the Gaza war or the dismantling of settlements in the West Bank. "The very existence of Israel, as a symbol of Jewish survival, is a provocation to those unwilling to recognize the Jewish people’s right to identity and security," Schwarz-Friesel concludes.

Between the Right and the Left

Mass demonstrations in support of Gaza and anti-Israel rhetoric from left-wing politicians and intellectuals have triggered an unexpected shift: more and more European Jews are beginning to see right-wing populist forces as potential allies. Their promises to combat Islamization and crack down on antisemitic aggression—primarily coming from radical Islamists and the far left—are perceived as offering real protection, albeit at the cost of political compromise.

"Today, the main threat to Jews comes from Muslims and far-left radicals," says Shmuel Lewitzy, the rabbi of Rouen. He explains that some in the community vote for far-right parties not out of sympathy, but as a counterweight: "The left normalizes antisemitic discourse under the guise of anti-Zionism. And the far right hates Muslims—which, dangerous as that logic may be, ends up reducing hostility toward Jews."

Polling data confirms this troubling trend. According to a study by the Representative Council of Jewish Institutions in France (CRIF), antisemitic stereotypes are held at roughly the same rate among supporters of both Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s France Unbowed (LFI) and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally—55% and 52%, respectively. But views on Hamas differ sharply: 25% of LFI backers express sympathy for the group, and 44% refuse to recognize it as a terrorist organization even after the October 7 attack. Among Le Pen’s supporters, the corresponding figures are just 4% and 25%.

CRIF President Yonathan Arfi argues that "LFI has given antisemitism political legitimacy." The party holds a dominant position in the left-wing coalition New Popular Front, which won France’s snap parliamentary elections in 2024 but failed to form a government. Mélenchon himself is a deeply polarizing figure, known for his fierce criticism of Israel and, according to critics, rhetoric bordering on antisemitism. He has blamed Jews for the death of Jesus and referred to the French Jewish community as an "arrogant minority." After the Hamas attacks in October 2023, he refused to condemn the militants, calling them a "resistance movement."

The Fondapol and AJC survey reveals deep concern among French Jews: 92% see LFI as the political force most responsible for the rise in antisemitism, and 57% say they would consider emigrating if an LFI candidate wins the next presidential election. "It seems France has no future for Jews," said Moshe Sebbag, chief rabbi of the Grand Synagogue of Paris, commenting on the success of the leftist bloc. He urged young Jews to consider making aliyah to Israel.

Against this backdrop, right-wing populists across Europe have seized the opportunity to distance themselves from their xenophobic image by demonstrating overt loyalty to Jewish communities and support for Israel. One of the most telling examples is Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch Party for Freedom. After winning the November 2023 elections, his party has portrayed Israel as "the only true democracy in the Middle East" and proposed relocating the Dutch embassy to Jerusalem while shutting down the mission in Ramallah.

Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s National Rally, condemned the Hamas attack on Israel as a "pogrom on Israeli soil" and claimed that her party is "the best shield against the Islamic fundamentalism that threatens French Jews." Some of her party members joined a solidarity march with Israel organized by the Jewish community. This marked a prelude to a major policy shift: in February, Israel lifted its ban on official contacts with three far-right parties—France’s National Rally, the Sweden Democrats, and Spain’s Vox. Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar stated that these parties’ current profiles are no longer as radical as they once were and ordered diplomatic ties to be restored. Soon afterward, National Rally president Jordan Bardella confirmed he intended to visit Israel and speak at an international conference on combating antisemitism.

As Sébastien Mosbah-Natanson, associate professor of sociology at the Sorbonne, explains, Jewish voters in France have long tended to support the political mainstream, avoiding the fringes. "Of course, the far right was traditionally unacceptable to Jews. But that is now changing. Le Pen and other right-wing leaders have made their support for Jews and Israel explicitly clear," he notes.

This shift has begun to show in election results: in districts with a significant number of Jewish voters, National Rally candidates performed better in July than in previous elections.

Nevertheless, a substantial portion of the French Jewish community still cannot bring itself to vote for the far right. Le Pen’s party has not fully shed the legacy of its past: her father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, founder of the National Front, was repeatedly convicted of inciting hatred and denying the Holocaust. The party itself has long harbored radicals with neo-Nazi sympathies.

Analyst Jean-Yves Camus notes that some Jewish voters have opted instead for Reconquête—the political movement led by writer Éric Zemmour, himself of Algerian Jewish descent. Despite a similar ideological stance, Reconquête does not carry the same historical baggage.

Skepticism toward Le Pen stems not only from her party’s past, but also from doubts about her ability to govern effectively. Many in the Jewish community view her economic program as poorly aligned with liberal market principles. There is also concern over proposals to restrict ritual slaughter and ban religious symbols—echoing measures against halal meat and hijabs. According to Camus, such restrictions could affect kosher slaughter as well. He believes that by the 2027 election, a more acceptable candidate for many Jewish voters might be Interior Minister Bruno Retailleau, who also advocates tougher immigration policies.

The Alternative for Germany (AfD) party, which achieved strong results in the European Parliament elections, has also declared full solidarity with Israel. In a statement issued by its parliamentary group on October 7, 2023, the party said: "We condemn the Hamas terrorist attack in the strongest possible terms. We stand in full solidarity with Israel and the Jewish people." The AfD had previously called for a total ban on the BDS movement, which advocates for boycotts and sanctions against Israel.

Yet elements of the ideology within AfD remain fundamentally at odds with the values of the Jewish community. These include the downplaying of the Holocaust, the promotion of antisemitic stereotypes, and the spread of conspiracy theories. One of the party’s founders, Alexander Gauland, once claimed that the Third Reich was merely a "speck of bird droppings" in Germany’s thousand-year history and expressed pride in the actions of German soldiers in both world wars.

AfD representatives have repeatedly called for an end to school trips to concentration camps and for abandoning Germany’s deep collective reckoning with its Nazi past. "They are openly challenging the societal consensus on the importance of Holocaust remembrance," says Ksenia Krimer. "At the party’s most recent convention, even Elon Musk echoed these views from the stage. But it’s important to understand—he was merely repeating what party members and supporters have long and consistently said."

Unlike other European far-right parties with whom Israel has recently reestablished ties, AfD remains excluded from official contact. The party’s leaders are not trusted by Germany’s Jewish community either. Several years ago, when Frauke Petry was at the helm of AfD, she claimed the party was defending German Jews by opposing Muslim immigration. But the Central Council of Jews in Germany issued a forceful statement at the time, calling AfD "a racist and antisemitic party" that "spreads hate, divides society, and threatens democracy."

That position remains unchanged. Ahead of Germany’s snap Bundestag elections in February, Council President Josef Schuster urged the country’s 103 Jewish communities not to support either the AfD or the newly formed Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), a party combining far-left politics with anti-Western rhetoric. In his letter, he emphasized: "Antisemites from the far right and radical opponents of Israel and Ukraine from the far left have found political refuge in AfD and BSW… For the Central Council of Jews in Germany, it is clear that these parties do not aim to strengthen the well-being of German society."

According to experts, antisemitism in Europe is no longer confined to any one political camp. "We are attacked by Hamas sympathizers, by far-left activists marching under anti-imperialist slogans, by Islamists, and by the far right. People who oppose one another on nearly every other issue are united in their hatred of us," says Sigmount Königsberg, antisemitism commissioner of the Berlin Jewish community. "And they are doing it with a level of fury we have never seen before."

It’s Happening Again

Sydney Preacher Called Jews "Malicious" and "Murderers."

Court Ordered Him to Publicly Admit Racism, but Notices Have Yet to Be Published

EU Migration Policy Shifts Sharply to the Right

Even Centrists Now Back Deportations, Offshore Camps, and Rewriting the European Convention