Since September 2025, U.S. forces have been conducting an operation in the Caribbean Sea against vessels that, according to the U.S. administration, are used to transport narcotics from Venezuela. During this period, at least 21 vessels have been destroyed and no fewer than 83 people have been killed.

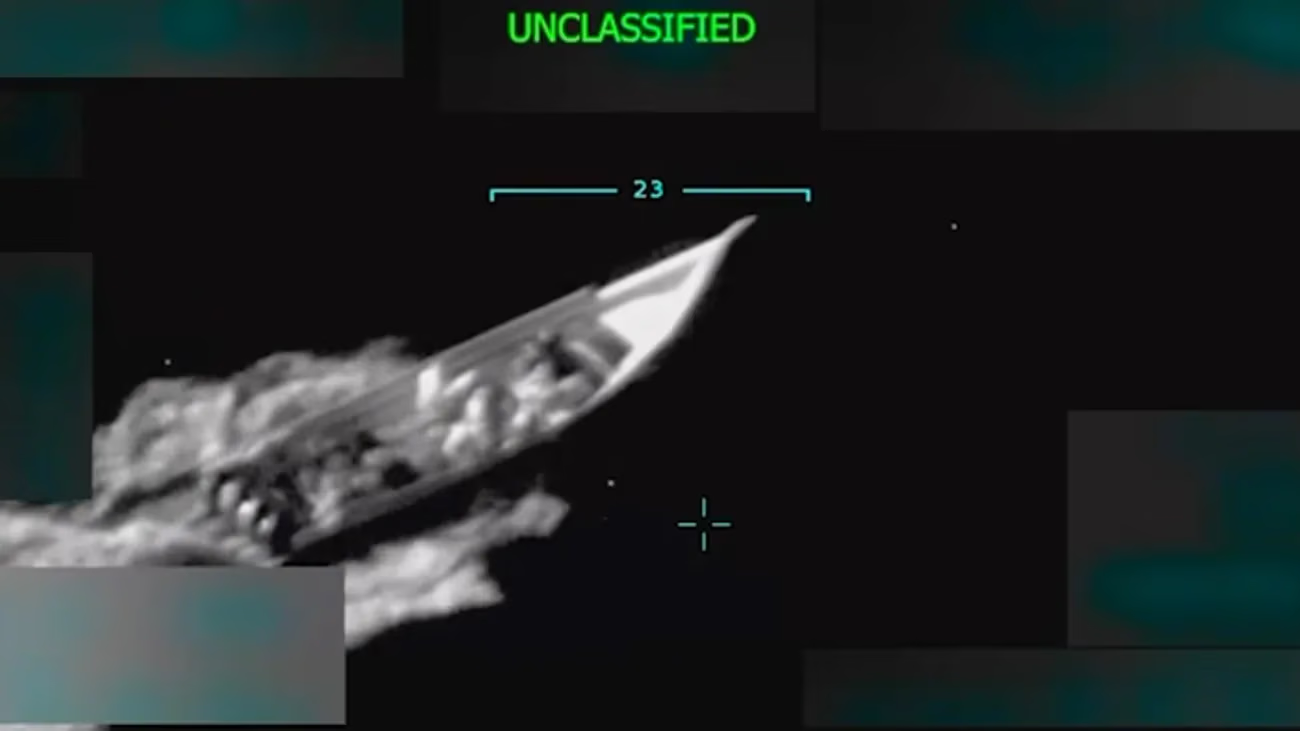

On November 28, The Washington Post, citing anonymous sources, disclosed details of the first strike. It took place on September 2. A reconnaissance drone detected a vessel carrying 11 people off the coast of Trinidad, after which it was hit by a missile. The Pentagon soon released footage of the attack.

As The Washington Post reported, the drone later recorded two survivors clinging to debris. A second strike targeted them. Admiral Frank Bradley, who commands the operation, issued the order in line with Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s verbal directive to «kill them all». The Pentagon did not publicly acknowledge the second strike.

Legal concerns about the operation had surfaced before. But after The Washington Post investigation and the White House’s confirmation that the article’s account broadly reflects the events of September 2, calls for a formal review came not only from Democrats but also from many Republicans in Congress.

On December 2, Hegseth stated that he had watched the first strike live but had not seen any survivors, had not ordered a second strike, and had not been present when it occurred because he had left for another meeting. In his account, the decision was made by Bradley, and Hegseth stressed that he fully supports it.

The boat destroyed by a U.S. Navy strike on September 2, 2025.

By December 5, Bradley was testifying at closed congressional hearings, where he showed lawmakers footage of the second strike. The proceedings are classified, and lawmakers who attended have offered differing summaries of his remarks. Only one point is consistent: Hegseth’s directive did not sound like «kill them all»—it referred to a specific order to destroy the narcotics on board and the 11 people transporting them.

The Trump Administration Defends a Deadly Follow-Up Strike on a Cocaine Boat

The White House Relies on a Secret OLC Memo Authorizing Such Targets to Be Engaged

The U.S. Is Massing Forces Near Venezuela

The Scale of the Military Presence Goes Far Beyond Counter-Narcotics and Points to Preparations for Seizing Key Facilities

The Trump administration maintains that the United States is in a state of «armed conflict» with drug cartels, treating them not as criminal networks but as armed groups. Within this framework, those who transport narcotics by sea are designated as combatants, and their actions are interpreted not as smuggling but as military operations. As a result, the government relies not on law-enforcement agencies but on the armed forces to counter them.

Outside the administration, this reasoning has gained almost no traction. But even if one accepts it, international law explicitly forbids targeting people who are out of combat, wounded, or shipwrecked. And if the fight against narcotics trafficking is not considered an armed conflict—contrary to the position of the White House, the Pentagon, and the U.S. Department of Justice—then all 83 people killed by American strikes qualify as victims of extrajudicial executions. Many international-law experts share this view.

Normally, military operations of this kind involve legal advisers who assess actions under the laws of war, weigh risks, and prepare the necessary documentation. Yet, according to reporters, professional lawyers played only a minimal role this time. Hegseth, moreover, is known for his distrust of them.

As early as November, it emerged that the Justice Department had drafted a classified memorandum describing the counter-narcotics campaign in the Caribbean as an armed conflict. The document states that even if this position is later deemed erroneous—by a court ruling or a change of administration—all strikes carried out while the memorandum is in force should nonetheless be treated as lawful.

A similar situation unfolded around the use of torture in the CIA’s secret prisons in the 2000s. During the presidency of George W. Bush, the Justice Department drafted a memorandum that effectively authorized the use of torture against terrorism suspects. In 2009, the new attorney general, Eric Holder—appointed by Barack Obama—launched an investigation into the conditions in those facilities, but the question of torture itself was not pursued precisely because a memorandum existed that had legitimized the actions carried out under its authority.

The episode involving the second strike on September 2 may become the subject of a separate inquiry. Given the Justice Department’s position, legal consequences are unlikely—but political repercussions are possible. If Congress concludes that Hegseth, Bradley, or anyone else committed a war crime, lawmakers could cut off funding for the operation and initiate impeachment proceedings against the defense secretary or even President Donald Trump.