The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado sparked celebration among her supporters worldwide—and fierce condemnation from the ruling government. President Nicolás Maduro called Machado a “demonic witch” and the prize itself “immoral,” claiming it “encourages violence and war instead of peace.” He argued that in the past, Machado had urged the United States to intervene militarily to overthrow Venezuela’s leadership.

The situation is further complicated by the presence of U.S. naval forces off Venezuela’s coast. Officially deployed to combat drug trafficking, the contingent includes at least seven warships, a submarine, and the amphibious group Iwo Jima with around 2,500 Marines. This has raised fears that the show of force could escalate into direct intervention—and that the Nobel award may serve as its prelude.

Heir to the Oligarchy

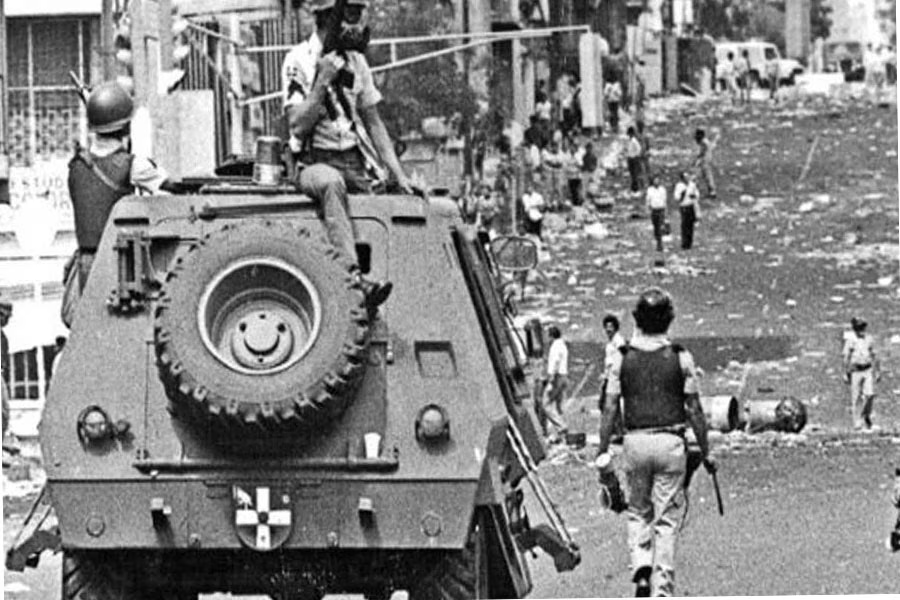

María Corina Machado hails from the elite of “eastern Caracas”—the wealthiest part of the Venezuelan capital, traditionally home to descendants of white Catholic families. Her father, Enrique Machado Zuloaga, owned the metallurgical company Sivensa as well as assets in the banking and construction sectors. This elite held political power for decades, often resorting to harsh measures against dissent. During the 1989 protests, up to 3,000 people were killed by the military.

The elites enjoyed the backing of the United States, which viewed Venezuela as a bulwark against communism and a reliable source of oil. American companies controlled extraction, while much of the country’s population remained poor and illiterate—by 1989, as many as 20% of Venezuelans could not read.

The economic crisis triggered by falling oil prices led to a deep rift in Venezuelan society. Riding that wave, former army officer Hugo Chávez came to power in 1998, declaring a “Bolivarian Revolution” built on the support of the poorest segments of the population—including Afro-Venezuelans, Indigenous communities, and mestizos.

Chávez nationalised key industries, including oil, removing U.S. companies from control. The revenues were redirected toward social programmes, while oil exports shifted toward China. This led to a short-term rise in living standards but also fuelled inflation, corruption, and inefficiency in public administration.

Despite systemic flaws, Chávez remained popular until his death in 2013. The 2002 coup attempt was repelled by mass protests, leaving the United States—which had rushed to recognise the new government—in an awkward position.

A New Opposition Leader

María Machado began her career in charitable initiatives before studying at Harvard and Yale—programmes designed to cultivate pro-Western leaders from the Global South. Upon returning home, she founded the NGO Súmate, which monitored elections and was funded in part by grants from the U.S. Congress–backed National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

In 2004, Machado organised a referendum on Chávez’s removal from office, in which 60% of voters ultimately supported the president. She denounced the results as fraudulent. In 2010, she was elected to parliament as part of the opposition coalition Democratic Unity Platform and continued to criticise the government, calling Chávez “a source of hatred and destruction.”

By the time of his final election campaign in 2012, Chávez was already battling cancer. He won the vote but died in March 2013, handing power to Nicolás Maduro.

Economic Collapse and Political Crisis

Maduro faced strong opposition from the outset. In the 2013 snap election, he won by a narrow margin. The subsequent collapse in oil prices and the resort to printing money triggered hyperinflation—reaching 250% in 2016. A fixed exchange rate, price controls, and ration cards failed to halt the crisis. Corruption, rising crime, and mass emigration only deepened the country’s decline.

The opposition grew more active. In 2015, it won a majority in parliament, prompting a backlash: in 2017, Maduro created a Constituent Assembly, effectively stripping parliament of its legislative power. In 2018, Maduro was re-elected, but the opposition refused to recognise the results.

In 2019, parliamentary speaker Juan Guaidó declared himself interim president. He was recognised by the United States and several Western countries, but Maduro retained power thanks to military support—Chávez had purged the officer corps after the failed coup of 2002.

An Ambiguous Choice

Today, Venezuela remains mired in a deep crisis—economic, political, and social. The opposition calls for a return to the pre-revolutionary order, but a significant share of the population—especially those who have remained in the country—continue to believe in Bolivarian ideals. Meanwhile, growing external pressure, including the U.S. military presence, only reinforces the government’s narrative of “imperialist plots.”

In this context, the Nobel Peace Prize awarded to María Machado takes on added significance. For some, it is a symbol of international support for democracy. For others, it is a signal of possible intervention. That means the consequences of this decision could reach far beyond the realm of symbolic diplomacy.