In June, the United Nations concluded its international conference on ocean issues. Dozens of countries pledged to step up protection efforts and invest billions of euros in preserving marine ecosystems. The statements sounded promising: participants vowed to establish new protected areas, restrict industrial fishing, and restore coral reefs. Yet beyond the summit hall, the outlook remains grim. The ocean is rapidly losing its ability to stabilize the climate, produce oxygen, and sustain food chains. Its ecosystems are being depleted by relentless fishing, pollution, and global warming. And while scientific solutions exist, they are not yet commensurate in scale or speed with the pace of destruction.

In May 2025, David Attenborough—the world-renowned British naturalist and one of the leading voices in environmental documentary filmmaking—released a new film titled Ocean. Even before the opening credits, viewers are warned in place of the usual age rating: this film may cause fear.

And the fear is warranted. Some of the most disturbing scenes are linked to bottom trawling—a method of industrial fishing where massive nets, weighed down with metal gear, are dragged across the ocean floor. In addition to catching fish, they churn up tons of sediment and sand, leaving behind a barren seabed stripped of life. Not only entire ecosystems perish, but also a wide range of marine creatures—from tiny shrimp to large lobsters. What remains after a trawler passes looks, on screen, like the aftermath of a bombing raid.

Official trailer for David Attenborough’s film Ocean

Yet the most lingering fear left by the film is anxiety over the ocean’s own survival. David Attenborough, who turned 99 this year and has spent nearly a century observing nature’s changes, delivers a stark message: without a healthy ocean, humanity has no future. Today, he says, the forces destroying marine life far outweigh those trying to protect it.

Still, the film is not without hope. Attenborough emphasizes the ocean’s astonishing capacity for recovery. "If we leave it alone," he says, "it won’t just recover—it will thrive in ways no living person has ever witnessed."

The Ocean as Climate Regulator, Oxygen Source, and Reservoir of Biodiversity

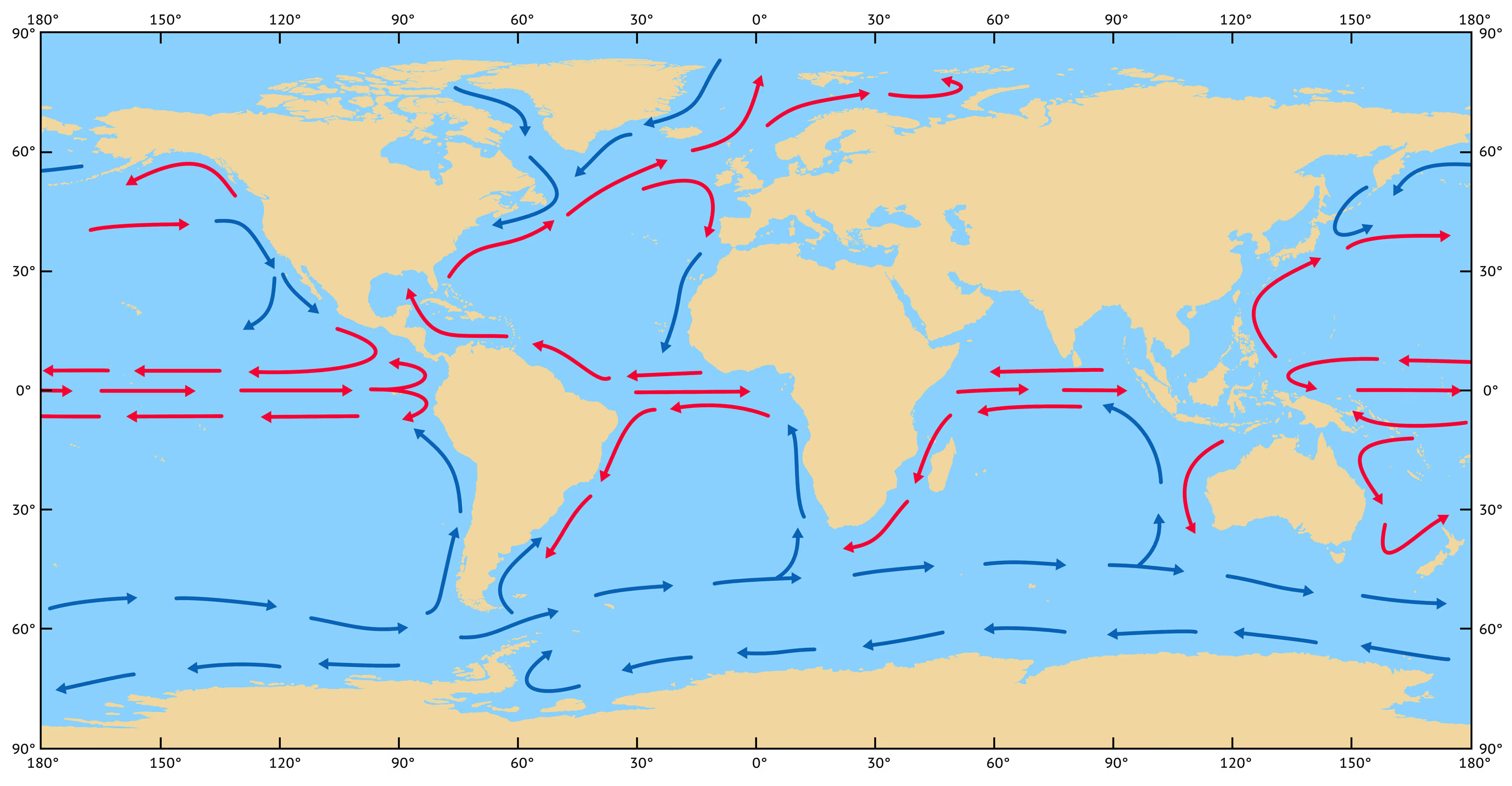

Covering more than 70% of the planet’s surface, the ocean plays a central role in maintaining climate balance. Its warm currents flow toward the poles, cool down, and return, influencing weather systems across the globe. But the climate crisis is disrupting this fragile circulation: currents are shifting, and with them, the climate in regions far and wide.

Map of surface currents in the world’s oceans.

Without the ocean, we would quite literally have nothing to breathe. It produces around half of all the oxygen on Earth—more than all the tropical forests combined. The source is microscopic organisms collectively known as phytoplankton: algae, bacteria, and other drifting life forms capable of photosynthesis. In addition to generating oxygen, they play a crucial role in the carbon cycle. The carbon they absorb settles on the ocean floor when the organisms die, locking it away from the atmosphere. Without this process, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air would be about 30% higher, leading to even faster global warming.

Roughly 80% of all known species live in the ocean. Each plays a role—from marine worms that break down organic matter to sharks that control fish populations. Marine life not only provides humans with protein-rich food, but also with medicines. Compounds derived from ocean organisms are now used to treat cancer, viral infections, and cardiovascular diseases.

And finally, the ocean is a vast source of economic value. In 2023, global trade in ocean-related goods and services hit a record $2.2 trillion. The largest share—$725 billion—came from marine and coastal tourism.

Overfishing, Warming, and Pollution Are Causing Coral Bleaching, Phytoplankton Loss, and the Collapse of Food Chains

The primary threat facing the ocean today is rooted in economic interests—overfishing. Each year, an estimated 1.1 to 2.2 trillion fish are caught globally—200 times the human population. In 1974, just 10% of global fish stocks were considered overexploited; today, it’s nearly 38%. In other words, in more than a third of the world’s fishing zones that once teemed with life, fish populations have all but vanished.

This threatens not only the livelihoods of coastal fishing communities but the very stability of marine ecosystems. Entire species are disappearing under market pressure. Over the past 40 years, the population of Pacific bluefin tuna has declined by around 80%—driven largely by demand for sushi. Overall, 75% of marine species are now at risk of extinction, often due to indiscriminate fishing methods. Bottom trawling, where nets are dragged along the ocean floor, results in bycatch rates of up to 46%—marine life that is unwanted and discarded. In the Mediterranean alone, more than 172,000 sea turtles were killed this way between 2000 and 2020.

Industrial trawler operating in open waters.

Fishermen retrieving pieces of coral reef from a trawl net after industrial bottom fishing.

Dead sea turtle entangled in a fishing net.

Warming is delivering an additional blow. The year 2024 was the hottest on record for ocean temperatures. One of the main casualties has been coral reefs. Under extreme heat, corals expel the symbiotic algae—zooxanthellae—that give them color and provide nutrients. This process, known as bleaching, doesn’t kill corals instantly, but it leaves them highly vulnerable. If temperatures don’t drop quickly, the reefs die.

Over the past 18 months, around 84% of coral reefs worldwide have experienced bleaching. In some regions, between 20% and 93% of corals have died. The destruction affects not just marine ecosystems but also entire coastal economies that depend on tourism and fishing.

Even more alarming is the impact of ocean warming on phytoplankton—the foundation of the entire marine food web. These microscopic organisms are where the ocean’s cycle of life begins. Their collapse reverberates through the entire chain: from zooplankton to fish, to seabirds and marine mammals. A shortage of these "invisible" life forms ultimately means death for the ocean’s largest animals.

During a prolonged marine heatwave in the northern Pacific from 2014 to 2017, home to one of the world’s largest humpback whale populations, numbers dropped by 20%. More than 7,000 whales died due to a lack of food—zooplankton and small fish.

In 2024, NASA launched a satellite that recorded the emergence of an increasing number of so-called ocean deserts—zones with critically low nutrient levels and an almost complete absence of phytoplankton. This means that entire regions of the ocean are becoming biologically dead.

Climate change not only destroys phytoplankton but also alters its behavior. Some species, when exposed to warming, begin to bloom excessively and release toxins harmful to other forms of life. In the spring of 2025, waves washed dozens of sea lions and dolphins ashore on California beaches, suffering from seizures and poisoning. Along the coasts of Santa Barbara and Ventura alone, over 150 sea lions and around 50 dolphins were found poisoned by algae—some died, while others had to be euthanized.

Climate threats are compounded by another long-term disaster—plastic pollution. According to various estimates, between 8 and 10 million tons of plastic waste enter the ocean each year. Some forecasts suggest that by 2050, the mass of plastic could outweigh the biomass of all oceanic fish—though the accuracy of such predictions remains debated. Still, the scale of pollution is undeniable, and its effects—from microplastics inside marine animals to decaying ghost nets that kill everything in their path—are becoming increasingly irreversible.

The Heat Ahead

'Climate Realism'

A World Three Degrees Warmer—and Colder in Blood

Marine Heat as the New Normal

What’s Behind the Oceans’ Unprecedented Warming?

New Global Push to Protect the Ocean: Agreements, Initiatives, and the Limits of Their Impact

Efforts to protect the ocean have been underway for years, but meaningful progress remains elusive. The latest attempt came in June 2025 at a four-day UN Ocean Summit held in Nice. The event brought together leaders from 60 countries and 190 ministers—an attendance level that reflects the magnitude of the crisis.

The summit’s central issue was advancing the High Seas Treaty, formally known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. It is the first legally binding international instrument designed to protect marine life in waters that belong to no single state.

Until 1982, the high seas remained a lawless zone where natural resources were exploited without regulation. That year, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea introduced obligations to protect marine environments even beyond national jurisdictions. But the agreement had little practical effect—predatory fishing continued unchecked.

The new treaty provides for the creation of marine protected areas on the high seas and obliges countries to conduct environmental impact assessments before launching large-scale resource extraction—whether fishing, construction, or underwater drilling. It also requires states to share scientific data, including discoveries with potential medical value, especially with developing nations—such discoveries should not become private property.

Formally adopted by the UN in 2023, the High Seas Treaty must be ratified by 60 countries to enter into force. By the start of the summit, 31 states had done so; by its conclusion, the number had risen to 50. Several other governments pledged to finalize ratification soon, meaning the agreement could come into effect as early as 2026.

The summit also saw the announcement of other initiatives. Germany unveiled plans to clear the Baltic and North Seas of sunken munitions. A coalition of 37 countries, led by Panama and Canada, pledged to combat ocean noise pollution. Indonesia, in partnership with the World Bank, launched so-called "coral bonds"—a financing tool for reef restoration. The European Union promised to invest €1 billion in projects to preserve marine ecosystems.

One of the most high-profile announcements came from French Polynesia, which declared the creation of the world’s largest marine protected area—nearly 5 million square kilometers. Similar plans to establish or expand protected zones were announced by Spain, Chile, Portugal, and several other countries. In total, around 20 new reserves are planned.

In practice, this means that within such zones, industrial fishing, tourism, shipping, and resource extraction may be restricted or fully banned. Scientific monitoring is conducted there, and access is completely closed during spawning or migration periods.

Today, there are more than 5,000 marine protected areas worldwide, officially covering about 8% of the ocean’s surface. However, many of these zones still allow activities that damage ecosystems—including bottom trawling. According to more stringent estimates, less than 3% of the ocean is under full protection.

Lack of Political Will and Funding Slows Progress on Global Environmental Agreements

At the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in 2022, countries adopted the global "30 by 30" initiative, committing to place at least 30% of land and ocean under effective protection by 2030. This ambitious goal reflects a consensus that without large-scale systemic measures, fragile ecosystems cannot be preserved.

Yet despite the declarations, real progress remains limited. Environmental groups estimate that achieving this target for oceans alone would require around $16 billion per year. Currently, funding is ten times lower—just $1.2 billion annually. And according to a review of national strategies, many countries are not ready to make the necessary political and financial commitments. Of the 137 national plans submitted to the UN this year, only 42% contain a clear pledge to meet the 30% target. More than half propose less ambitious measures—or omit specific figures altogether. Russia is among the countries that have not submitted any plan for land or ocean protection.

With just five years left until 2030, the UN acknowledges that "30 by 30" is an enormous challenge—one that can only be met through global cooperation. But it is already becoming clear: the world is moving too slowly and too unevenly to succeed.

A similar situation exists in the fight against plastic pollution. UN negotiations on a global plastics treaty ended without agreement in 2024. In Busan, countries failed to reach consensus even on basic principles: whether to curb plastic production itself or focus solely on recycling.

The divisions fall along geopolitical and economic lines. A coalition of 100 countries—mainly from Europe, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific region—is calling for radical measures: a ban on non-recyclable plastics and production caps on the rest. Opposing them are oil exporters, including Saudi Arabia and Russia, who argue that production limits are unnecessary and that the focus should instead be on improving recycling systems.

Meanwhile, the problem continues to grow. In the Pacific Ocean, the so-called Great Pacific Garbage Patch is expanding—a massive accumulation of plastic waste that resembles not an island, but a dense soup of microplastics. Its surface area is now three times the size of France.

In the absence of binding international oversight, individual innovators are stepping in. The Dutch organization The Ocean Cleanup, founded by student Boyan Slat, has developed a device capable of cleaning plastic from the ocean at a rate equivalent to one football field every five seconds. Yet even the most advanced technologies, scientists warn, cannot keep pace with the scale of pollution—unless single-use plastics are banned and the global consumption model is fundamentally restructured.

The next round of UN negotiations on plastic pollution is scheduled for August 2025 in Geneva. The upcoming treaty is already being compared to the Paris Agreement on climate—in both its significance and the challenges of implementation. The question is whether this time an agreement will not only be reached, but actually enforced—or if it will end, as so often before, with lofty promises and little follow-through.