On July 12, The New York Times published a report by Nanna Heitmann from Russia’s Kursk region—one of the few pieces by Western journalists to be filed from the Russian side of the front line. The article, titled "A Landscape of Death: What Remains Where Ukraine Invaded Russia," drew sharp criticism from Ukrainian officials, who accused the author of amplifying Russian propaganda. At the same time, the piece was praised by Apti Alaudinov, commander of the Chechen "Akhmat" unit.

Heitmann is a German photojournalist, a Pulitzer Prize finalist and World Press Photo winner. She works with the Magnum cooperative and lives in Moscow. Her reporting and photo essays on everyday life in wartime Russia have been published in The New York Times, Time, Le Monde, Stern, and other outlets.

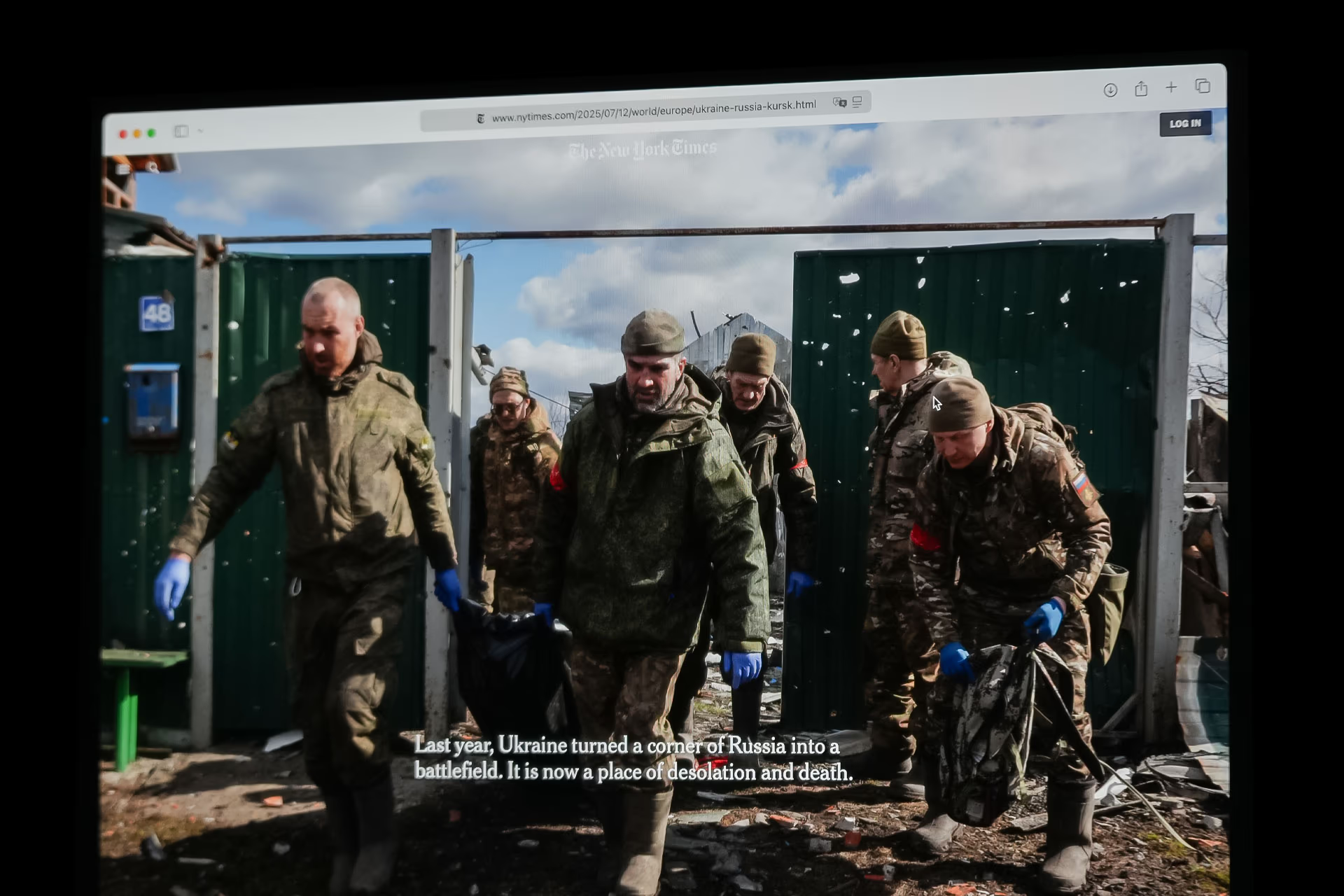

In March 2025, Heitmann spent six days in the Kursk region, shortly after Russian forces retook control of the town of Sudzha, which had been occupied by Ukrainian troops since August 2024. Her report describes scenes of chaos and destruction—burned homes, unexploded ordnance, corpses, the stench of decay, and the constant sound of fighting. At the same time, she notes that residents blame not only the Ukrainian army, but also the Russian authorities for leaving the region without aid.

One of the article’s subjects, Oksana Lobodova, said her mother died in the village of Russkoye Porechnoye, while her sister fled from neighboring Cherkasskoye Porechnoye to Kursk. "Seven months of winter without water, food, medicine, or electricity. Sick elderly people. What’s the difference—were they killed or did they just die? They were simply abandoned," Heitmann quotes her as saying.

Locals also shared that many of them had Ukrainian roots. One interviewee, Lyubov Blashchuk, is originally from Western Ukraine; Lobodova has relatives in Kharkiv. Yet when talking about the causes of the war, they often echoed narratives promoted by Russian state media—about "NATO expansion," "brainwashing of Ukrainians," and so on.

Interestingly, when describing the behavior of soldiers—both Ukrainian and Russian—residents emphasized that they "did not touch" civilians and even provided food and medicine. "They were fighting each other, but no one touched us," the report states.

Heitmann also interviewed fighters from the Chechen special forces unit "Akhmat," who took part in Operation "Truba" (or "Stream")—an assault on Sudzha involving a flanking maneuver along a gas pipeline. One of the soldiers said the operation's conditions had caused him health issues. According to Alaudinov, one person died of poisoning, two were discharged, and others are undergoing long-term treatment.

The New York Times piece sparked a mixed reaction: Ukrainian officials accused the newspaper of echoing the Russian perspective, while pro-Kremlin media and Chechen military figures praised the article. Against this backdrop, the report becomes not just a piece of journalism, but part of a broader struggle over how the war is interpreted.

In her article about the destruction in Russia’s Kursk region following Ukrainian occupation, photojournalist Nanna Heitmann does not explain how she gained access to the front-line zone. The only clue is her admission that she was occasionally accompanied by fighters from the Chechen special forces unit "Akhmat." Moreover, she was in direct contact with the unit’s commander, Apti Alaudinov, who later publicly praised her work—calling it a "truthful reflection" of events in the region. His praise was broadcast on Russia’s state-run Russia 1 channel—one of the main instruments of government propaganda.

The fact that a Western journalist was escorted by a unit accused in the West of committing war crimes sparked outrage in Ukraine. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that The New York Times report violated journalistic standards and contributed to the spread of Russian propaganda. Ukrainian Foreign Ministry spokesman Heorhii Tykhyi called the editorial decision "utterly foolish," emphasizing that this was not "the other side of the story" but the legitimization of war criminals.

Visits by Western journalists to the Russian side of the front are extremely rare. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, it has been nearly impossible for independent media to obtain accreditation for frontline reporting—due to laws on "fake news" and "discrediting the army." Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov has openly acknowledged that the country is in a state of "wartime censorship." As a result, Western reporting from inside Russia is typically limited to daily life, and only occasionally—such as in Heitmann’s case—touches on the war itself.

According to a statement by Kursk region governor Aleksandr Khinshtein, 93 foreign media outlets visited the area in March 2025, shortly after Ukrainian forces withdrew. However, none published in-depth reports from the scene—except for Heitmann. This alone sets her work apart, but also raises questions: how was access arranged, and under what conditions was filming permitted?

Amid ongoing repression of independent Russian journalists, Heitmann’s report stood out as both unexpected and stark in contrast. Back in 2022, when Kommersant correspondents reported from Donetsk and Mariupol, the newspaper faced criticism for complying with censorship and presenting an evasive narrative. By contrast, despite military censorship, international journalists continue to work actively from the Ukrainian side. It was Ukrainian reporters Evgeniy Maloletka and Mstyslav Chernov from Associated Press who won both the Pulitzer Prize and an Oscar for their reporting from besieged Mariupol.

The core criticism of Heitmann’s piece extends beyond the circumstances of her trip to the content itself. Ukraine’s Center for Countering Disinformation, part of the National Security and Defense Council, noted that The New York Times report fails to mention that it was Russia that initiated the war against Ukraine. The absence of context, according to Ukrainian officials, distorts the reality of the conflict. "Neutrality without context becomes disinformation," the agency stated in an official release.

Neither Heitmann nor The New York Times has responded to the criticism. Still, the structure of the report itself—juxtaposing the emotions of civilians and the realities of occupation with comments from members of the "Akhmat" unit—has already triggered heated debate over the limits of journalistic objectivity during wartime.