As artificial intelligence threatens to upend labor markets worldwide, Nvidia chief Jensen Huang urges caution against dramatizing long-term risks and points instead to a shift already under way: a sharp surge in demand for skilled trades.

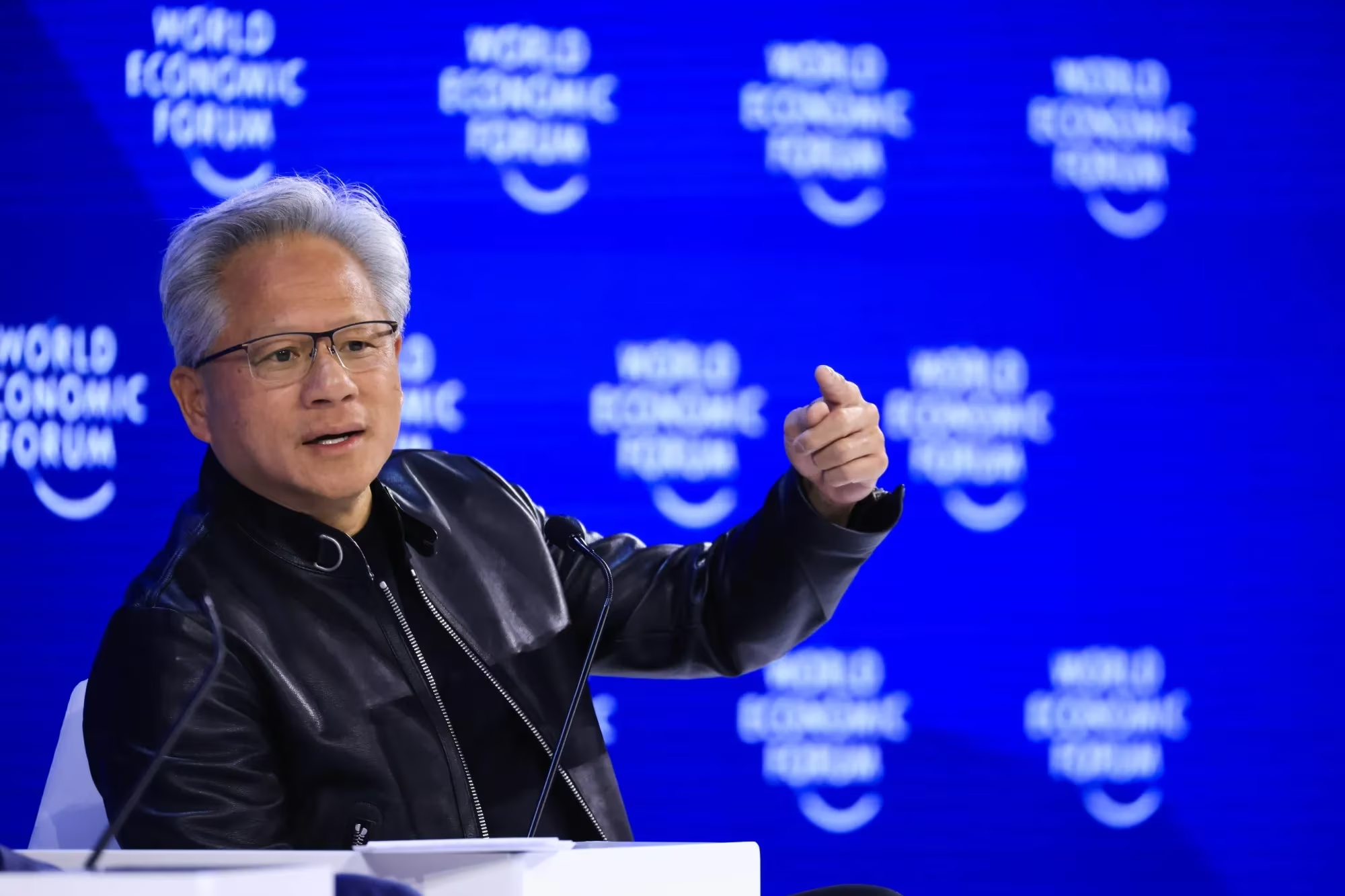

According to Huang, plumbers, electricians, and construction workers can expect “six-figure incomes” driven by the large-scale buildout of data centers required to run and train AI systems. He made the remarks in an interview with BlackRock CEO Larry Fink at the World Economic Forum in Davos. Huang stressed that technological progress will require one of the largest infrastructure projects in history, with investments running into the trillions of dollars.

“We’re seeing a very serious boom in this area. Wages have nearly doubled,” Huang said. “Everyone should have the opportunity to earn a good living. You don’t need a PhD in computer science for that.”

These remarks echo statements made a day earlier in Davos by Palantir chief Alex Karp. He, too, praised workers with vocational training, arguing that AI will create more local jobs and, in many cases, reduce the need for mass migration. CoreWeave CEO Michael Intrator later pointed to the “physical side” of the AI boom, citing growing demand for plumbers, electricians, and carpenters.

Nvidia, the largest maker of chips for advanced AI models, has emerged as one of the main beneficiaries of the race to build data centers. According to average analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg, the company could come close to generating $200bn in revenue from data-center chip sales in 2025. For now, most of that income comes from the biggest players—Microsoft, Meta, Amazon, and Alphabet—but Nvidia is increasingly signing contracts with smaller operators. Altogether, technology companies have already committed to spending around $500bn on data-center leases in the coming years.

The impact of AI on the labor market is already being felt. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has warned of a “white-collar bloodbath” that could wipe out up to 50% of entry-level positions. The company’s AI system, Claude, has drawn attention for its programming capabilities—precisely in the area where junior developers typically work.

“We are entering a world in which the tasks of entry-level engineers—and possibly a significant share of the work done by more experienced specialists—are increasingly being performed by AI systems. And this is only the beginning,” Amodei said in an interview at Bloomberg House in Davos. While he believes the overall benefits of the technology will outweigh the harms, the risks of mass unemployment and underemployment, he said, require active policy responses.

“Unfortunately, an entire class of people will emerge who, in many industries, will struggle to adapt,” he added.

In his exchange with Huang, Fink conspicuously steered clear of sensitive topics—above all China. Nvidia’s sales to the country remain politically fraught, and the company is awaiting a decision on whether—and in what volumes—it will be allowed to ship its chips there. A day earlier, Amodei had likened Nvidia’s chip exports to China to selling nuclear weapons to North Korea.

Huang is expected to visit China later this month, seeking to restore access to one of the company’s key markets for AI chips. The timing is critical: the US has recently eased chip-export restrictions in place since 2022. Nvidia remains barred from selling its most advanced models to China, limiting Beijing’s ability to develop cutting-edge AI, but the company will be permitted to export its previous-generation H200 chips.

China, for its part, is expected to approve the import of H200 chips for commercial use in the first three months of 2026, while banning their use for military purposes, sensitive government bodies, critical infrastructure, and state-owned enterprises. According to Bloomberg News, several of China’s largest technology companies, including Alibaba and ByteDance, have already privately expressed interest in purchasing more than 200,000 of these chips each.