In world politics, epochal shifts rarely happen overnight. The Cold War was defined by nuclear balance: states sought formulas to deter one another and avert catastrophe. In the 1990s, it seemed that globalization would become the new order: capital and technology flowed freely across borders, wars appeared to recede into the past, and American institutions and platforms became universal standards.

That vision quickly cracked. Global networks turned out not to be guarantees of stability but chokepoints that could be manipulated for political ends. Sanctions, technology controls, and access to finance all became new levers of power. And they are now wielded not only by the United States but also by those Washington long regarded as dependent.

The world has entered a phase in which economic interdependence is no longer seen as a public good. It has become an arena of struggle, comparable in significance to the nuclear rivalry of the past century. This is the logic in which today’s moves by America, China, and Europe must be understood.

In June, Washington and Beijing announced a "framework agreement"—an event that drew little attention but marked a turning point in global political economy. It was neither the triumph of unilateral grandeur dreamt of by Donald Trump, nor a return to the managed rivalry of the Biden era. A new epoch had begun—"weaponized interdependence," in which the United States for the first time found itself subject to the very methods it had long imposed on others.

Today’s politics hinge on sanctions, supply-chain disruptions, and export controls. For two decades, America wielded them unilaterally. Now the levers are turning against it. The Trump administration struck a compromise: it eased restrictions on semiconductor exports in exchange for China lifting barriers on rare-earth supplies. Synopsys and Cadence returned to the market, and Nvidia once again sells AI training chips.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio admitted that China had "captured the market" for rare-earth metals, putting the United States in a "difficult position." The deal underscored the limits of isolationism: Washington was forced to soften its threats to avoid paralyzing its own industries.

As in the nuclear age, America now faces the task of rebuilding its security system—this time in the economic realm. China is adapting with remarkable speed, while Europe is lagging. All major powers must search for strategies in a world where interdependence has become a weapon.

Origins of "Weaponized Interdependence" and the Transformation of Globalization into a Tool of Pressure

The era of weaponized interdependence emerged as a byproduct of globalization. After the Cold War, the internet, social networks, the dollar, and SWIFT created a global infrastructure centered on the United States. Chip production was spread across Europe and Asia, but the key software remained in the hands of American companies.

The system appeared robust until the United States turned it into a universal instrument of coercion. After September 11, financial and technological networks were deployed first against terrorists and then against entire states. When Trump withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal, European corporations suddenly found themselves under the threat of U.S. sanctions.

The term "weaponized interdependence" emerged in 2019: control over communications, finance, and production was concentrated in the hands of a few. In Washington it was called "a beautiful thing," yet every move triggered a counteraction. The global economy began to reorganize itself along the logic of offense and defense.

Biden entrenched the course: sanctions against Russia and China, and plans to divide the world into technological blocs. This was meant to secure U.S. leadership, but instead accelerated rivals’ efforts to build alternative ecosystems.

How China Turned Vulnerabilities Into Leverage and Forced the U.S. to Negotiate

China made weakness a source of power. After Edward Snowden’s revelations in 2013, technological self-reliance came to be seen as a matter of national security. Trump’s threats against ZTE and Huawei hastened the course toward "self-sufficiency."

By the 2020s, Beijing had built an export-control regime, extending it to rare earth metals. It became not only a tool for restricting supplies but also a means of tracking global demand.

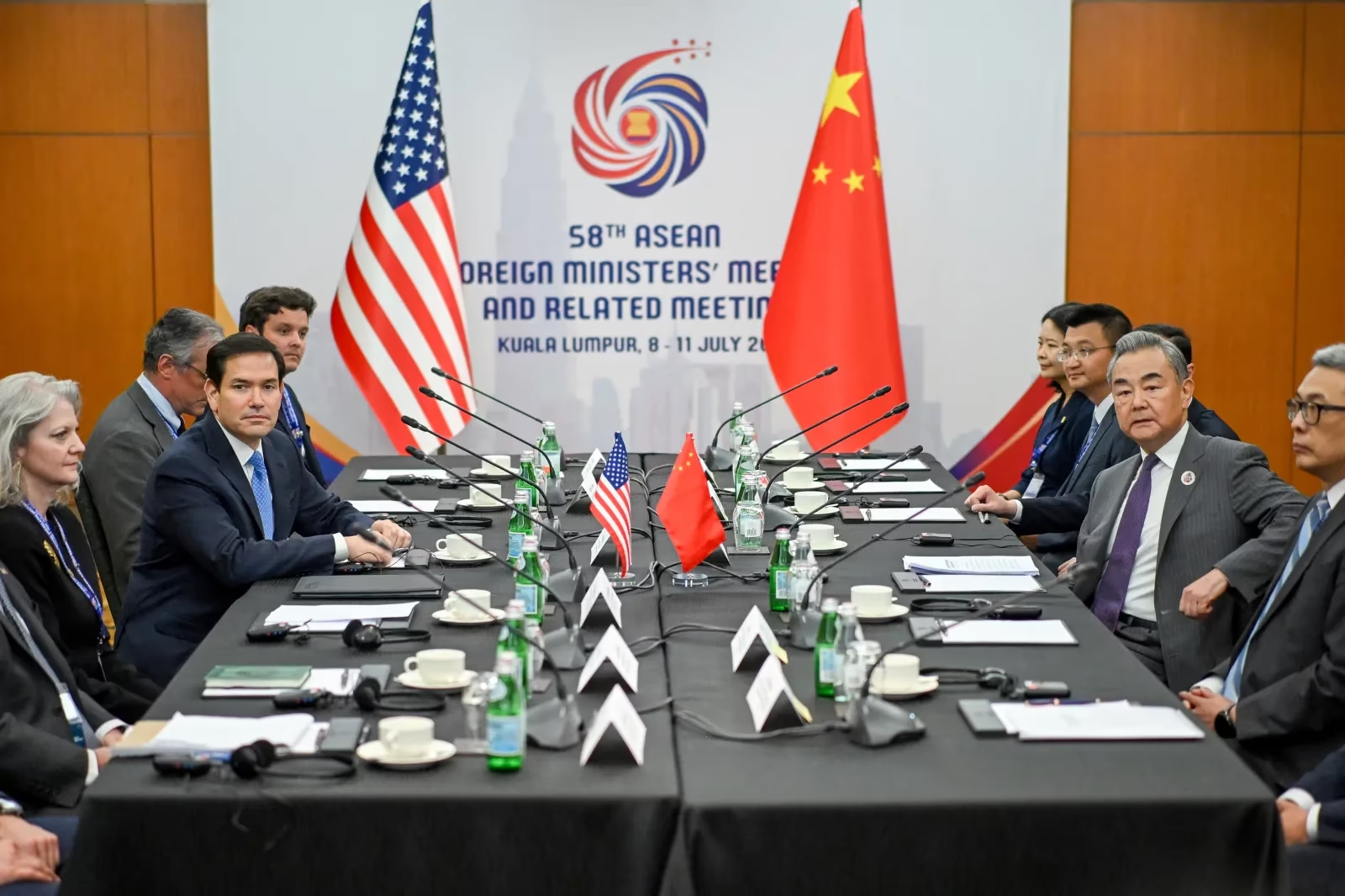

Marco Rubio meets Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. July 2025.

In June, American and European companies found themselves at an impasse: without Chinese magnets, carmakers risked halting production. Trump was forced to admit on Truth Social: "FULL MAGNETS, AND ANY NECESSARY RARE EARTHS, WILL BE SUPPLIED… BY CHINA."

In the long run, excessive state intervention may slow innovation, but in the short term China is wielding its leverage as effectively as the United States once did.

Europe Between Washington and Beijing: Ambitions Without Institutions

Europe has the makings of a geoeconomic superpower: SWIFT and Euroclear, firms such as ASML and Ericsson, and the world’s second-largest market. But it lacks an institutional machine comparable to that of the United States or China. The "EuroStack" project has stalled, and after Russia’s invasion Europe’s security once again rests on America.

Internal divisions within the EU deepen its weakness. Germany and others dilute measures against China to shield their corporations. Brussels has expertise but few mechanisms for coordination. Even the "anti-coercion instrument" is weighed down by legal hurdles and is not taken seriously.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen speaks to the press in Brussels. June 2025.

Europe thus remains a player with ambitions but without the tools to realize them. Ursula von der Leyen warns of the risks, but the union continues to live up to its reputation as EACO — Europe Always Chickens Out.

America’s Weaknesses: Eroded Institutions and Chaotic Use of Pressure

If Europe is institutionally weak, the United States is undermining itself deliberately. The Trump administration froze hiring in key agencies, cut back the National Security Council and the State Department. OFAC and the Bureau of Industry and Security lost staff and expertise. Decisions increasingly depend on the president and his closest circle.

The White House is also weakening the material foundations of power: it promotes cryptocurrencies, lifts sanctions on Tornado Cash, and turns a blind eye to sanctions evasion. In energy, the emphasis is on hydrocarbons, while investment in new technologies is cut back. As a result, the United States risks either becoming dependent on Chinese innovations or settling for outdated ones.

The erratic use of pressure undermines the appeal of the American platform. If China pulls ahead in energy and AI, many countries may opt for its technological stack instead.

Economy Without a Manual

The Real Economy Is Out of Sight

Without Rethinking Data on Supply Chains, Digital Services, and Vulnerabilities, Decisions Are Made Blindly

An Economy Where No One Pays Now

Global Debt Is Growing Faster Than the Ability to Service It

The End of Globalization as We Knew It

Economics in the Age of New Borders

The U.S. Economy as a Source of Global Instability

American Policymaking Increasingly Resembles That of Emerging Markets

A New Nuclear Moment: Can Washington Forge a Strategy in an Age of Interdependence

In the early decades of the nuclear age, the United States invested in institutions that ensured stability. Today it needs a comparable strategy for the economy. But that requires strengthening expert structures rather than dismantling them.

Washington has spent too much time thinking about how to exploit interdependence, and too little about when its use is illegitimate. Allies have lost trust: Trump regards them more as vassals. "We are witnessing a growing acceptance of the fragmentation of the global economy," warns Lawrence Summers.

The United States now faces a choice: continue relying on coercion and hasten its own decline, or refrain from overreach and seek alignment with liberal states. As in the nuclear age, steps toward détente and new institutions are needed. Otherwise both security and prosperity will be at risk.