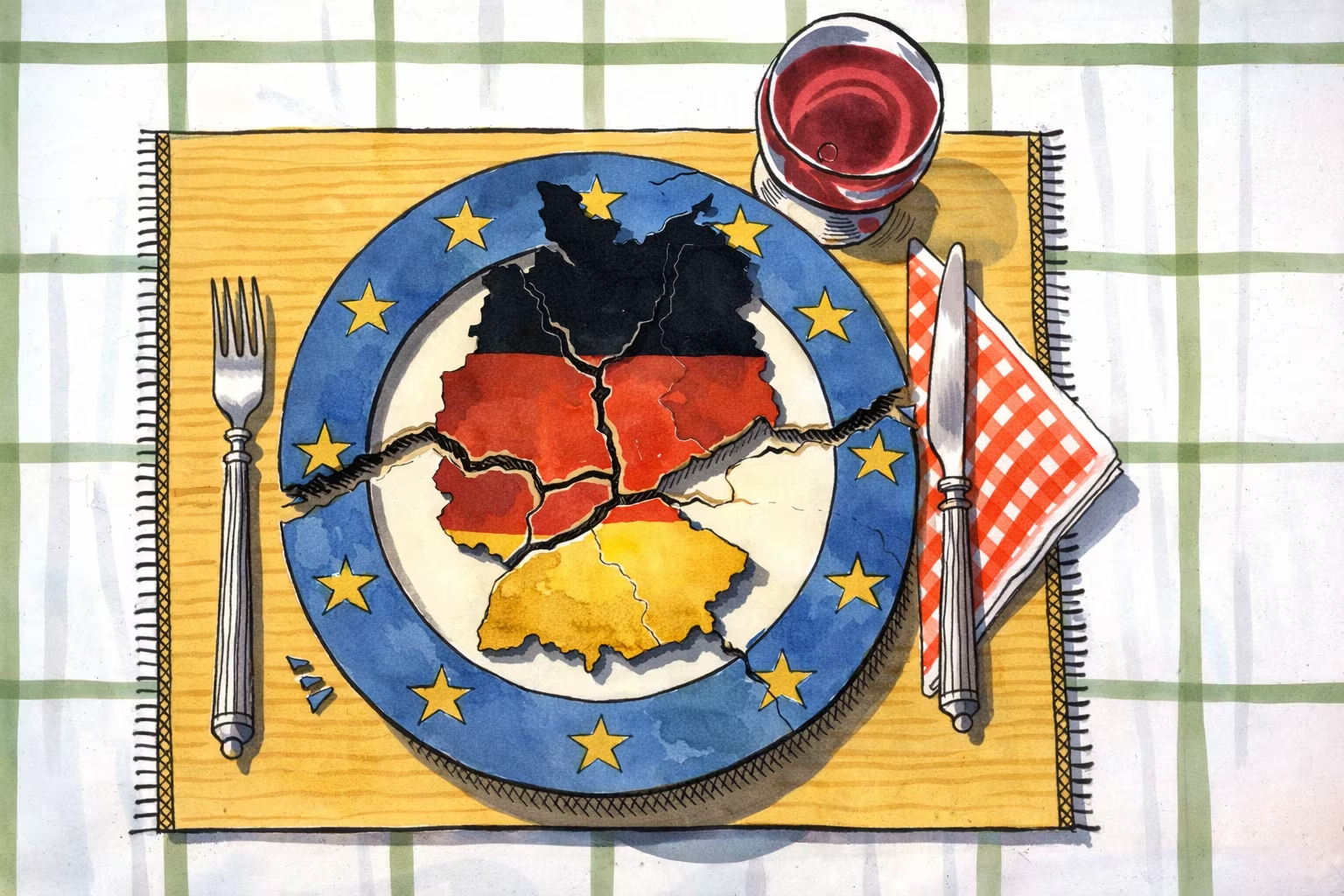

Friedrich Merz came to power with a combination of opportunity and expectation that is rare in modern Germany. The easing of the debt brake gave his government access to unprecedented financial resources, allowing it to sharply expand defense spending while simultaneously launching a renewal of the country’s economy. Yet months after the election it has become clear that fiscal latitude alone is no substitute for political strategy. Successes in foreign policy and a strengthened German role in European security have not translated into trust at home, where a sense of economic stagnation, uncertainty, and the absence of a clear vision for the future persists. Against this backdrop, pressure from the far-right AfD is intensifying, while the governing coalition’s inability to offer a convincing course of domestic reform is turning the economic question into the principal risk to the stability of Merz’s leadership and to Germany’s role in Europe.

Before Friedrich Merz’s victory in Germany’s parliamentary elections this February, the country faced a financial dilemma. Economic stagnation demanded deep reforms and large-scale investment to revive industry, while the United States was pressing for higher spending on collective defense. The dispute over how to reconcile these competing priorities within the budget ultimately led to the collapse of Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government. Determined to avoid a repeat of that outcome, lawmakers in Merz’s “grand coalition”—the Christian Democratic Union, the Social Democratic Party, and the Greens—agreed to rely on borrowing to finance both objectives. As a result, Germany suddenly found itself with far more money at its disposal.

Seven months on, however, Merz’s government has still failed to chart a persuasive course for economic transformation or to convince voters that better times lie ahead. Decisive steps to boost defense spending have reinforced Germany’s leadership in Europe, but they have eroded the chancellor’s standing at home. A significant share of his political capital has been spent at international summits—engaging with U.S. President Donald Trump and defending Ukraine—leaving Merz exposed to accusations that he is overly focused on foreign policy at the expense of domestic concerns. The right-wing, Russia-friendly Alternative for Germany has seized on economic anxiety, expanding its support in opinion polls and accusing the government of squandering national resources to build a “war economy.” At the same time, despite praise from the White House for Berlin’s defense posture, the Trump administration is gradually weakening Merz’s position by normalizing the AfD and—according to the recently published National Security Strategy—other “patriotic European parties.”

100 Days of Merz

Germany Faces the Rise of the Far Right, the Decline of Traditional Parties, and a Crisis That Will Shape the 2026 Elections

Trump’s Adviser Meets with AfD Leaders in Berlin

Contacts with the MAGA Circle Help German Far-Right Figures Strengthen Their Political Legitimacy

The government has little room left to maneuver. Abandoning reforms aimed at reviving and accelerating economic growth would risk eroding public support for the centrist coalition. If the Christian Democrats and Social Democrats continue to cede ground to the AfD, they may forfeit their ability to form viable governing coalitions in the future. The “grand coalition’s” failure to offer a path toward economic renewal could trigger the government’s premature collapse and call into question Germany’s long-awaited role as Europe’s leader—with negative consequences for U.S. interests as well.

Angela Merkel, Germany’s former chancellor and Merz’s principal rival, came to power in 2005, sidelining him and other contenders. She then held office for 16 years, consistently avoiding reforms that could have proved politically painful. That approach is no longer available to Merz.

How Merz Lifted Budget Constraints to Fund Defense and Investment

Friedrich Merz came to power with a mandate to strengthen Germany’s defenses while restoring its economy. To escape the perennial dilemma faced by European governments—choosing between “guns and butter”—he broke with his party’s traditional commitment to strict fiscal discipline and pushed through a loosening of the so-called debt brake. Introduced in 2009, the mechanism capped the budget deficit at 0.35 percent of GDP. Shortly after the federal election, parliament amended the rule to allow unlimited borrowing for defense, thereby avoiding sweeping cuts, including to social spending. In parallel, Merz agreed to allocate an unprecedented €500 billion for investment in the country’s aging infrastructure.

At the same time, Berlin is seeking to meet its commitments on European security. At the NATO summit in The Hague in June, Germany pledged to raise defense spending to five percent of GDP by 2035, with 3.5 percent earmarked for core defense needs. Merz has taken advantage of a degree of fiscal flexibility that many European partners lack: France, for example, is already burdened by high debt, whereas years of adherence to the debt brake left Germany with a more balanced budget and, consequently, greater room to maneuver. Under pressure—including from Donald Trump—Merz has already announced a sharp increase in military spending; Germany is expected to meet its NATO commitments well ahead of schedule. The country’s total defense budget for the next five years is estimated at €650 billion—the largest in the European Union. Around €8.5 billion a year is allocated to support Ukraine.

Merz has also played a pivotal role in securing the supply of U.S. weapons to Ukraine after the Trump administration formally ended direct military assistance. He reached an agreement with the U.S. president under which Berlin and other European capitals purchase Patriot air-defense systems from Washington and transfer them to Kyiv. In July, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte publicly highlighted Germany’s leadership and determination in upholding Europe’s collective security.

Why Economic Stagnation Is Undermining Support for the Coalition and Boosting the AfD

Yet such accolades remain elusive at home. Even before taking office, Merz understood that trying to meet security demands while tackling domestic economic problems could prove contradictory and trigger a populist backlash. Most Germans support higher military spending financed through borrowing. But a substantial share of the public also expects debt-financed funds to be directed toward other priorities—industry, the pension system, and education.

Germany’s industrial growth has been stagnant since 2019. The government’s Council of Economic Experts offers a notably restrained outlook: economic growth of just 0.2 percent in 2025 and 0.6 percent in 2026. Europe’s economic engine is visibly lagging behind its peers in the G7. The export-oriented model is coming under additional pressure from an influx of cheap, state-subsidized high-tech goods from China, threatening the automotive sector and millions of jobs. The shortfall in domestic investment since the introduction of the debt brake in 2009, combined with Washington’s new tariff policy and China’s overproduction-driven model, has effectively rendered Germany’s old economic framework unsustainable.

After the reform of the debt brake, Merz’s “grand coalition” gained access for the first time to resources that allow it to increase defense spending while pursuing economic transformation—options that previous governments did not have. Historically, German society has viewed deficit financing with caution, forcing the authorities to carefully justify the shift in course and to demonstrate the effective use of unprecedented additional funds. Merz has promoted an economic reform agenda dubbed “Agenda 2030,” centered on tax relief, deregulation, and partial cuts to social spending. Yet this has proved insufficient given the scale of accumulated challenges. The plan relies on conventional economic tools and largely sidesteps the systemic challenge posed by China to German and European industry. Further concern stems from infighting within the coalition over the allocation of the €500 billion infrastructure fund: fears are growing that borrowing will be used as a temporary patch for long-standing problems and a means of meeting electoral expectations, rather than to create new economic opportunities.

The lack of tangible results is playing into the hands of the opposition Alternative for Germany. In 2021, during his bid for the party leadership, Merz pledged to halve support for the AfD. Today the situation is reversed: the party’s ratings have reached record highs, and a December poll by the Forsa institute showed the AfD overtaking Merz’s conservative camp. While Germany’s far right broadly supports higher defense spending, it opposes financing it through debt and harshly criticizes the loosening of the debt brake. Its stance rests on a nationalist conception of German military power that favors distance from the constraining frameworks of the EU and NATO.

Defense funding has helped Merz establish a working relationship with Donald Trump. Yet figures within the MAGA movement—most notably Vice President J.D. Vance and Congresswoman Anna Paulina Luna—are increasingly finding common ground with the AfD and encouraging closer ties. This poses a serious threat to Merz, who presents himself as a committed Atlanticist and seeks to keep postwar German conservatism anchored at the center rather than surrendering it to the radical AfD. The new U.S. National Security Strategy, which explicitly endorses nationalist conservative parties and even contemplates encouraging political change in countries such as Germany, further weakens his position.

As far back as the 1980s, Franz Josef Strauss, the legendary leader of the Christian Social Union—the Bavarian sister party of the Christian Democrats—warned that the far right must not be allowed to become the flank of mainstream conservatism; that role, he argued, should be filled by the CSU itself. Since then, Germany’s political landscape has changed dramatically. The AfD has entrenched itself as one of Europe’s most radical far-right parties. In May of this year, the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution classified it as extremist. Even so, the AfD has become the most successful far-right party in Germany since the Second World War.

Germany Postpones the Return of Military Service

Defense Minister Pistorius Blocks Coalition Plan to Partially Reinstate Conscription

Germany Will Deploy Troops to Help Reinforce Poland’s Eastern Border

From 2026, German Units Will Join the East Shield Program and Carry Out Engineering Works Along the Border With Belarus and Russia

Foreign-Policy Success Without Domestic Voter Trust

Merz faces a difficult crossroads. The risks stemming from a reduced U.S. commitment and Russia’s aggressive policy demand higher defense spending and active international diplomacy. The chancellor is acutely aware of what is at stake and is trying to persuade the public that foreign policy is directly tied to domestic well-being. Yet the experience of Helmut Kohl, who led Germany through reunification, suggests that foreign-policy achievements on their own do not guarantee electoral support.

After his first hundred days in office, Merz has proved even less popular than his predecessor Olaf Scholz, who became the first chancellor in decades to serve only a single term. According to a Forsa poll conducted in early December, 76 percent of Germans are dissatisfied with Merz’s performance as chancellor.

An additional threat comes from potential infighting over influence. Discontent is growing among conservatives over the dismantling of the debt brake. A younger wing of the party is pushing for pension reform, a move resisted by the Social Democrats. Moreover, within Merz’s parliamentary group there are figures who see no need to maintain a strict barrier against the AfD and are open to cooperation with the far right—an option Merz himself categorically rejects.

Despite tensions between the center-right and center-left, the coalition has so far managed to hold together, as early federal elections could bring the AfD closer to power. Even without a snap vote, the “grand coalition” faces a serious test in next year’s state elections. The AfD enjoys solid support nationwide and in several eastern German states leads its rivals by double-digit margins. If the party posts a major breakthrough at the next federal election, forming centrist coalitions will become even more difficult. In that case, both Merz’s time in office and Germany’s leadership role in Europe could prove short-lived.

Reforms as the Only Way to Preserve the Center and Germany’s Leadership

Undertaking painful reforms is nothing new for Germany and has generally made the country stronger over the long term. The unification of East and West Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall came with substantial economic costs and fostered resentment among many residents of the former GDR, who felt like second-class citizens. Anti-immigrant sentiment dogged Germany in the 1990s, requiring the development of integration policies. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder launched his “Agenda 2010” program to liberalize a rigid labor market and lay the groundwork for far-reaching economic change.

Merz must now deliver on his promise of renewal through his own “Agenda 2030.” More than a trillion euros are earmarked for defense and infrastructure projects over the next four years, giving the chancellor the fiscal tools he needs to reboot the economy and preserve the political center. Germany’s export-oriented model needs to be refashioned to stimulate domestic demand—both at home and across Europe. Additional investment is required in the defense industrial base to create jobs to replace those Germany is losing in traditional industries under pressure from Chinese exports. The true scale of the economic challenge posed by China is only now being fully recognized by Germany’s political leadership.

By default, Germany remains a champion of free trade. Yet it must coordinate its industrial policy more closely with EU partners to soften the impact of U.S. tariffs and China’s overproduction model—by identifying new trade avenues and fostering competitive European producers. In an environment of sluggish growth and an aging population, Berlin also cannot sustain current levels of social spending indefinitely. To preserve economic competitiveness, the country will have to raise the retirement age and ease the strain on public finances. Investment in innovation and the technologies of the future must not be subordinated to social outlays.

Such reforms will not make the AfD disappear overnight. In the short term, they may even strengthen the party’s position. As in other Western democracies, the far right in Germany is already embedded in the political system and is steadily eroding the standing of traditional parties. Even so, Merz and his coalition can reduce the AfD’s legitimacy if they succeed in persuading voters that safeguarding European security and investing in Germany’s defense can become sources of renewed economic growth and greater competitiveness. Managing relations with Donald Trump, deterring Russian aggression, responding to pressure from China, and easing domestic anxiety all require Merz’s centrist course—not the extremism of the AfD.