A rapid surge in the stock market, driven by a handful of headline-grabbing companies; executives promising sharp productivity gains from new technologies; steady GDP expansion even as the first signs of labour-market softening emerge—all this has happened before, in 2000. And the pattern is now reappearing, only amplified by the recent sell-off in some of this cycle’s marquee stocks.

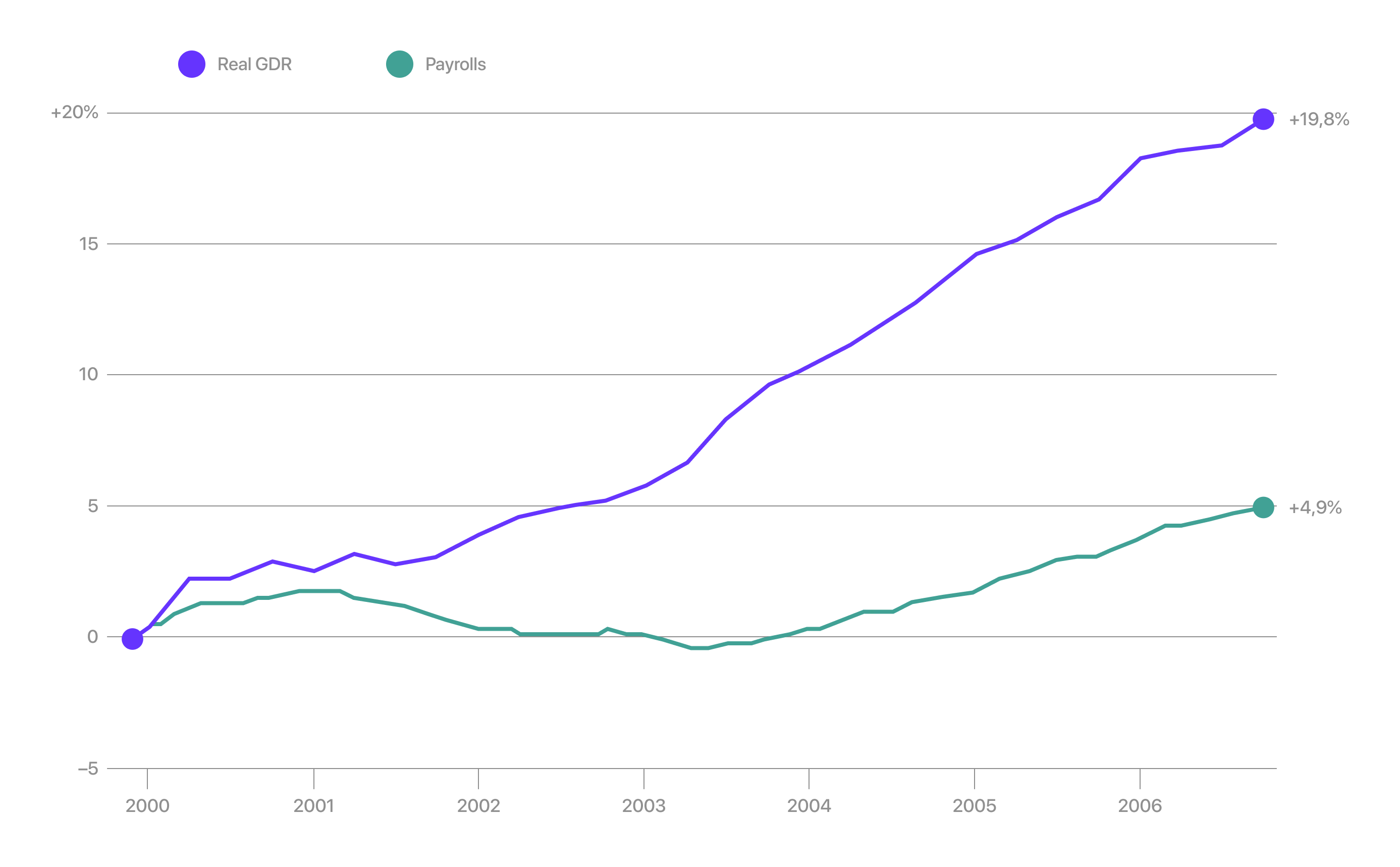

Combined Change in Employment and GDP

The experience of the turn of the millennium offers clues to how the next few years may unfold as businesses adopt labour-saving AI systems and investors reassess assets priced for flawless growth. Back then, even after the bubble burst, GDP kept expanding and consumer spending held firm—but the labour market endured a prolonged slump.

The S&P 500 peaked in March 2000 before entering a prolonged bear market. Employment growth turned persistently negative in early 2001. Economists later classified the episode as a brief recession, though an unusual and borderline one. GDP never posted two consecutive quarters of decline; by the end of 2001 it had even inched up by 0.2%, and in 2002 it returned to solid growth. The downturn was driven by a collapse in investment in telecommunications equipment. Personal consumption—the economy’s main engine—rose every quarter, supported by the 2001 tax cuts and the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate reductions.

The Global Economy Is Slowing, Though the U.S.-China Tariff Standoff Proved Softer Than Expected

The IMF Sees Risks From an Overvalued AI Market and Weakening Global Demand

Militarization of the Economy in the Age of Interdependence

The U.S. Loses Control of the Very Levers It Created, as China and Europe Turn Them Into Weapons

Yet the recovery in GDP did not translate into an improvement in the labour market. For workers, it meant a prolonged period of stagnation. In 2001 the economy shed 1.7 million jobs, and in 2002 a further 518,000. Annual employment growth remained negative until November 2003—two years after the formal end of the recession. By late 2003, the number of people employed in the economy was lower than in 1999, even as output had risen by 10%.

This combination of steady GDP growth and continued job losses reflected a surge in productivity. American companies were finally reaping returns on years of investment in information technology. At the same time, a wave of outsourcing and offshoring—enabled by technological progress and globalisation—allowed firms to expand the production of goods and services while relying on fewer working hours within the United States. High productivity ultimately makes society richer, but it comes with a painful adjustment phase for workers.

It is difficult to say today whether the share prices of today’s technology leaders will undergo a correction or whether generative AI will live up to the expectations of its most ardent proponents. But the early-2000s experience suggests that even during a far-reaching economic transformation a recession is not inevitable, and if one does occur it need not be severe. The adjustment period for the labour market, however, is unlikely to be painless—just as it wasn’t then—no matter how reassuring the national accounts may look.